The Land Trap, by Mike Bird: UK edition on the left, US edition on the right Mike Bird, writer for the Economist, has written an excellent book called The Land Trap, whose basic premise is that land is a big deal. If you’ve read my own book on that subject you’ll find many parallels in Bird’s, but his book has a second purpose. That purpose is to warn us of the titular Land Trap, which I expect will join other established terms like “Cost Disease,” “The Two-Income Trap”, and “The Resource Curse” in the economic lexicon.

The book can be summarized in five bullet points and one fun fact.

The five bullet points are:

Land is a big deal, and always has been

Land has only recently been financialized

Financializing land causes “The Land Trap”

It has short term benefits but devastating long term consequences

China serves as a perfect example of what not to do

The fun fact is this:

Fiat currency isn’t backed by nothing, as commonly supposed, but by land.

Mike opens with this anecdote:

We know more with some degree of certainty about Munnabittu—a Babylonian servant who lived in the dying days of the Bronze Age, who was otherwise a historical nobody—than we do about many of the kings, warriors, scholars and prophets who were born during the centuries and millennia that followed. We know about Munnabittu specifically and solely because of the land he possessed, the ownership and saga of which is carved into a piece of smooth black limestone around half a meter long.

Land grant to Munnabittu kudurru (source) Land was a big deal in the stone age, the bronze age, the iron age, and is still a big deal today. But why? Regular readers of this blog and my book will recall three features that make land a uniquely valuable economic asset. Land:

To this Mike adds three more properties that make land a uniquely valuable financial asset. Land:

The first three properties make land a powerful lever over the economy, while the second three make it the ideal kind of asset to use as financial collateral.

If you need a loan, a banker won’t just give you money trusting that you’ll pay them back later. They want you to pledge something valuable they can seize to cover their losses if you default. The better your collateral is, the more money the banker is willing to lend.

Most forms of material wealth make for inferior collateral. Jewelry can be stolen, tools rust away, machines obsolesce, furniture gets eaten by termites, and cattle get sick and die. Land, on the other hand, doesn’t even need to be stored in a vault. As long as the courts recognize your rightful claim to the land title, it’s yours.

Land being a big deal is nothing new, but something that is new is the so-called “commodification of land” by banks, which has made land an even bigger deal in the modern era. This is when title to land becomes an article that can be freely bought or sold just like any material good. According to Bird this practice was pioneered in the New World by American financial engineers.

Once upon a time, a freethinking American entrepreneur found fault in his country’s financial infrastructure, and suggested a novel idea—what if land ownership was encoded in a durable and authoritative ledger? Then, tokens backed by land records could be minted, and issued as a radical new decentralized currency. These tokens could facilitate commerce in an otherwise illiquid and stagnant economy bogged down by the limitations of its legacy currency system.

If you were thinking of crypto-bros like Packy McCormick, who famously advocated for putting real estate on the blockchain in the year 2022, you’d be wrong: it was Benjamin Franklin, and the year was 1729. In an essay titled “The Nature and Necessity of a Paper-Currency,” Franklin said, “For as Bills issued upon Money Security are Money, so Bills issued upon Land, are in Effect Coined Land.”

The problem Franklin and co. were trying to solve was a currency shortage. American colonists literally didn’t have enough physical doubloons, shillings, pieces of eight, etc., to facilitate transactions with one another, causing a huge drag on the overall economy. Paper currency could solve the problem, but it could only hold value if it was backed by something trustworthy. This was fifty years before the American revolution, so “the full faith and credit of the United States” wasn’t an option, and mother country Great Britain wasn’t interested, either. Franklin and co. therefore settled on land itself to bootstrap the new paper currency.

When I say that paper currency was “backed by land,” I don’t mean in the same sense that a $1 silver certificate can be redeemed for a silver dollar coin; it’s not like you can give the bank a dollar note and exchange it for so many square inches of land from their vault. Instead it works like this: a landowner takes out a loan, and the bank puts money in the borrower’s account, thereby issuing new currency. The loan is backed by the borrower’s land—if the debtor can’t pay back the loan, the bank seizes the land.

This was the perfect way to bootstrap America’s economy, given that it had a sparse population and little capital, but lots of productive land ripe for the taking. The borrower would pay for things like tools, materials, research, and workers, which would generate new wealth, with which the borrower would eventually pay back the loan. The new currency system could unstick the American economy by greasing its wheels with credit.

There was just one problem: the very idea was anathema to the entire traditional European understanding of land. In Britain as elsewhere, land was not simply a thing you could sell to someone else. If you were the Earl of Sussex, your lands were not your individual property—they belonged to your family line, and the last thing the aristocracy wanted was to let some foolish peer establish a dangerous precedent by liquidating his family line’s birthright just to settle his own personal debts. Additionally, the American colonists’ hunger for land helped spark the French-and-Indian war, further driving a wedge between the colonists and their mother country.

Eventually, however, the Americans got their way and land became a freely tradeable commodity. This unlocked the engines of financialization, and in the short term, things were good. America was a young country, the frontier was wide open, and every (free) man could reasonably count on eventually becoming a landowner. In this way the early American electoral standard of granting voting rights exclusively to landowners was at that time much more egalitarian than an equivalent policy back in Europe could ever have been.

American innovations in land title laws gradually made their way back home to England and spread from there throughout the modern world. The old feudal order was replaced with a financial one, which in the short term unlocked growth as the industrial revolution got under way, but as the twentieth century wore on would eventually lure many countries into the jaws of The Land Trap.

The Land Trap is when land slowly sucks up all your economy’s productivity, inflating a dangerous real estate bubble that eventually pops, leaving disaster in its wake. It progresses in five stages:

Banks lend money, using land as collateral

Cheap credit increases real productivity—people can now pay for tools, materials, research, and workers. In accordance with Ricardo’s law of rent, this gain in real productivity also causes land rents to rise, and with them, land selling prices.

Rising land values encourages land speculation

Land speculators buy land, and their speculative demand raises land prices further. Speculators pledge their land as collateral, and borrow even more money to buy even more land.

Land outcompetes other assets as an investment

Traditional investments like stocks, bonds, and going into business for yourself all contribute to the real economy by directing money towards tools, materials, research, and workers. In a rising real estate market, however, investors feel it’s safer and better to buy land and wait for it to go up in value. This not only bids up the price of land, but also sucks capital out of the actually productive part of the economy. That lost investment could have paid for tools, materials, research, and workers. Instead, it just inflates the price of land.

Increasing land values and shrinking investment slow the economy

Other sectors now have less money to pay rent, and land is more expensive. Workers and businesses now have to pay more in rent, have less money to pay it with, and must take out larger loans to buy their own property. Labor and capital now have less money and more debt. Less money gets spent on tools, materials, research, and workers, and productivity declines.

The bubble pops

Tenants can’t pay rent, so they get evicted and their businesses close.

Landlords can’t collect as much rent, so they can’t pay their mortgages, and banks foreclose on them.

The foreclosed land has dropped in value, so banks can’t cover their debts.

The banks’ debts get called in, and they go bust too.

Now there are fewer banks, so it’s harder to get a loan.

Otherwise healthy businesses with short term cash flow gaps go bust.

Those businesses’ workers lose their jobs.

Other businesses that depended on those workers as customers go bust.

New businesses can’t get started because everyone is broke and nobody’s lending the money needed to pay for tools, materials, research, and workers.

The economy stops growing and stagnates.

Periodic booms and busts driven by land speculation have happened again and again in human history, and Mike Bird makes the same conclusion that Henry George did in Progress and Poverty, namely that land and its financialization is one of the main driving forces behind the Business Cycle.

Mike points out that there were good reasons to make land a freely tradeable asset and to deploy it as a means of unlocking credit, turning his sights to post-war east Asia, home of the so-called “Asian Tigers.” Readers of the book How Asia Works will recognize many of the stories Bird recounts in chapters dedicated to Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Here are some highlights.

East Asian countries had long been dominated by hereditary landlords, much like their counterparts in Europe, but the aftermath of World War II put an end to that. In Japan, American reformers like Wolf Ladejinsky, a Ukrainian refugee influenced by Henry George, seized the opportunity to push forward radical land reforms, redistributing land to the peasants who worked it. A surprising ally turned out to be General Douglas MacArthur, leader of World War II’s pacific theater, and Supreme allied commander of the Japanese occupation. MacArthur needed no convincing of Ladejinsky’s ideas:

[MacArthur] witnessed the way in which large landlords dominated the Philippines’ economy and its politics. Like Ladejinsky, MacArthur had come to believe that the violence and unrest in the countryside was ultimately caused by the monopolies on land and the miserable condition of the peasantry.

MacArthur would not settle for half-measures and shamelessly used his influence to ram through maximalist reforms:

MacArthur’s authority was as close to that of an absolute monarch as any American has ever wielded anywhere. He was empowered to approve and veto legislation passed by the Japanese legislature and censor the media, and he was the primary force behind the drafting of the country’s new pacifist constitution. When it came to land, the change that MacArthur envisioned was not just an economic revolution, but a social one too. In November of 1945, even before Ladejinsky’s arrival, American newspapers carried an unsigned statement from the headquarters of the Allied occupation, reportedly dictated by MacArthur, that promised that “Japanese farmers and their families are about to be liberated from a condition approaching slavery.”

Bird points out that in Japan, Ladejinsky and MacArthur were playing land reform on “easy mode” with a conquered population that had no choice but to follow orders. Nevertheless, landowners were compensated with long term government bonds, and the peasants got the land. The results? Massive and immediate economic growth:

The incentives of former tenants shifted dramatically: hard work, investment and planning could now boost their earnings, which had previously been soaked up by distant landowners in the form of rising rents. An explosion in agricultural productivity followed, and crop yields swelled. Rising household incomes unlocked new opportunities.

Ladejinsky proceeded to go on a world tour of land reform, pushing the idea forward in many other countries, such as Taiwan. The looming threat of communism often provided sufficient motivation to win over reluctant incumbents:

Communists would always eventually pursue the collectivization of agriculture once they had taken power and secured control of the countryside, Ladejinsky argued. But before they took power, he had seen how they could foment turmoil by offering the tantalizing promise of land to impoverished tenant farmers. “The peasants, in sheer despair, believe the promises, not knowing that they will eventually be betrayed, their land nationalized, and they themselves herded into collective farms at the point of a bayonet,” he lamented in 1954. Development economist and land reformer Michael Lipton would later call collectivization the “terrible detour” in the politics of land in the developing world. The process Ladejinsky had seen in the early Soviet Union was repeated in Eastern Europe after the Second World War, in China under Chairman Mao Zedong, in the communist halves of both Korea and Vietnam, and in socialist Tanzania. It was always and everywhere a disaster, of varying proportions.

Ladejinsky’s philosophy is best summed up by this Photoshopped poster I made:

Back on the mainland, post-war China found itself plunged into civil war. The original Republic of China was founded by Sun Yat-Sen, who overthrew the Qing dynasty. He was a follower of Henry George, preached land reform, and was revered by Nationalists and Communists alike. Unfortunately, he died early and his successor, Chiang Kai-Shek, lost the mainland after a series of strategic blunders. One of these was to massacre peasants who had sided with and received land from the communists, which helped turn the rural population against him, forcing a retreat to Taiwan. Here Chiang “repented” on the land question:

With the war over, and on its new and much-reduced territory, the KMT revived Sun’s teachings on land, both out of principle and for new tactical reasons. The political calculus for the KMT had reversed: while they had sided with the landlords on the Chinese mainland, they had no reason to align themselves with the established class of landowners in Taiwan…Expropriating the island’s landlords would help Chiang to build a base of power in the countryside.

The results?

As in Japan and Korea, the change was rapid. The cap on rents depressed farm values, enabling tenants to buy plots from their landlords. Agricultural production rose sharply. In 1953, the policy turned to outright redistribution: Land was compulsorily purchased from large owners and offered to tenants at reduced prices. Landlords were paid in land bonds issued by the government, and they were given shares in the Japanese state-owned enterprises that the KMT government privatized.

Bird points out that land reform is not simply the act of giving land to the peasants, it’s also the imposition of a modern property rights framework, with a formal land title system backed by cadastral ownership records. “Modernizing” land ownership can be done independently of broader land redistribution efforts:

In 1984, the World Bank assisted the government of Thailand with an ambitious effort to formally title and document the country’s land, which proved to be a roaring success. The newly titled land was worth between 75 percent and 197 percent more than the previously untitled land. Farmers with property rights got better access to loans, and at lower interest rates. Titled land exchanged hands more often, its owners deployed more investment in materials and equipment, and farmers recorded higher crop yields. The Thai economy began to boom, and it seemed as if the pivot towards titling land was achieving what redistribution had intended to do under earlier land reform programs.

The chief limitation of land reform in all its guises is that it tends to be a one-time fix. An initially level playing field gradually erodes over time as financial interests seep in, and then it’s just a matter of time until the country falls face-first into the Land Trap.

There have been several key changes since the 1700’s that have changed how land speculation manifests in the modern day.

The first change is land financialization itself. Given that it started in America, it’s no surprise that the newly independent United States immediately suffered from real estate bubbles. Mike recounts how the American revolution was financed in large part by a man named Robert Morris, a land speculator. Known as the “financier of the revolution,” he went from riches to rags when Britain’s war with France put a squeeze on international credit, landing him in debtor’s prison. Bird posits that Morris and his fellow speculators may have sparked the first recession in American history.

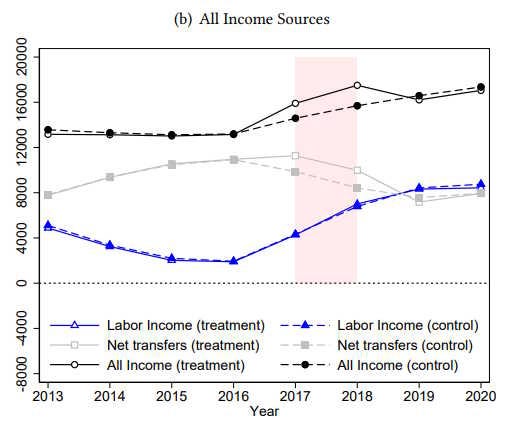

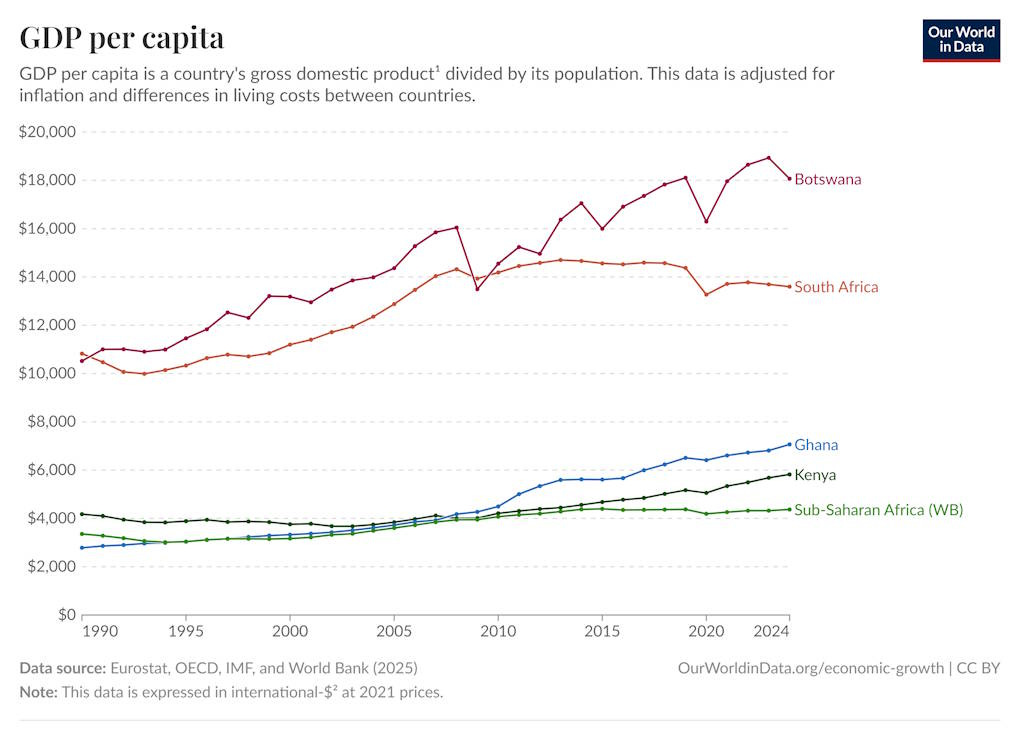

The second change is a shift in what kind of land is valuable. Many people don’t think land matters much in the modern economy, because they think of land primarily in agricultural terms. That’s only half right—it’s true that agriculture is a diminishing part of the economy, especially since the Green Revolution, which greatly increased crop yields worldwide. However, just as agricultural land values diminished, residential and urban land values skyrocketed. These three graphs from Spain, Britain, and France, all tell that same story:

Source: Capital in the 21st Century by Thomas Piketty

Source: Capital in the 21st Century by Thomas Piketty

On top of these, Bird adds three new financial trends unique to the modern era:

Real estate has become a much larger portion of the financial system

Land has become an increasingly large share of real estate prices

Restrictions on bank lending have loosened

In support of the first point Mike cites The Great Mortgaging: Housing Finance, Crises, and Business Cycles by Jordà, Schularick, and Taylor, which some of you may recognize:

The most maddening thing about the Land Trap is that this has happened again and again, and if countries would simply pay attention they might be able to learn from another and avoid it. Case in point—sixteen years prior to the global financial crisis, Japan suffered a catastrophic real estate crash that took decades to recover from.

In 1989 the New Zealand government sold a tennis court and playground located next to their embassy in Tokyo for 150 million $NZD, which works out to a quarter billion American dollars today. Mike’s entire chapter on Japan is filled with wild anecdotes like that, including how surging land prices fueled Japan’s organized crime gangs, the Yakuza, who made a steady living “encouraging” reluctant property owners to sell to eager property flippers.

Mike attributes this mania to a mentality dubbed “The Land Myth.” Post-war reforms unlocked such tremendous growth, and rising land prices along with it, that people thought the rise would never end. Economists of the time even described the Japanese economy itself as being literally “backed by land.”

Just as economies historically pegged their currencies to the value of gold until the early twentieth century, Japan’s economy was effectively pegged to the price of land…And just as the application of the gold standard ended in disaster for its adherents in the 1930s, so did the tight link between land and credit prove to be ruinous to Japan.

You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of land!

The fall was tremendous. Japan crashed so hard that it went from among the highest per capita income levels in the world in 1989, to having an economy less well off than Italy’s today. Japan has struggled mightily to recover ever since, but the silver lining is that Japan was hit by it’s real estate bubble early—Japan’s neighbors in China have only recently succumbed to it and now face difficult choices.

Mike next turns his attention to two former British colonies, both small, compact city-states with large Han Chinese populations, a history of British colonialism, popular trading ports, and which bootstrapped their modern transformation into urban mega cities through the use of land leases. These two city-states are Hong Kong and Singapore.

In both cities, the state effectively owns all the land and leases it out to citizens on long terms, such as 99 years, after which it returns to the state. These leaseholds can be freely traded between citizens, or passed on to heirs, though the time remaining on the lease does not reset. Since most people don’t live for 99 years, for all intents and purposes these leaseholds aren’t too different from regular property sales, with the caveat that in the long run the land will return to the government.

Despite starting in similar situations, they wound up with dramatically different economic outcomes, even before Hong Kong’s 1997 handover to the People’s Republic of China. As Hong Kong was dragged down into stagnation by the Land Trap, Singapore nimbly avoided it and rose to lasting success.

Hong Kong implement land lease sales with large up front payments, and negligible recurring fees thereafter, making them nearly indistinguishable from fee simple land sales. This, combined with Hong Kong’s anti-tax stance, led to a dependence on land lease sales as one of the main sources of state revenue. This gave the state a direct incentive to prop up land selling prices:

No matter the pain for residents hoping to buy the city’s modest apartments, or to operate businesses on the scarce square footage, rising land values made the life of the government far easier, while any fall in prices would pose an immediate strain on them.

Note the key word—land selling price. Because the key form of state revenue was effectively a land sale, and because there was basically no holding cost to land, the upfront selling price of land became what mattered most for government revenues, not the recurring rental value. Hong Kong pursued what became known in the 1970s as the “high land price policy.” The effects on Hong Kong’s industry was disastrous:

As early as 1965, the International Council for Scientific management noted, “High land prices have taxed the ingenuity of Hong Kong industrial entrepreneurs.” The squeeze on more land-intensive industries became more and more severe over the subsequent decades, and businesses that needed significant space saw their costs surge far faster than their sales could keep up. The industries that had powered Hong Kong’s rise to prosperity found bases elsewhere. Manufacturing shrank from 20 percent of the city’s economic output in the middle of the 1980s to just 5 percent by the end of the century, and 1 percent today. In fact, bank lending to most kinds of businesses has declined as a share of all credit. Fifty years ago, manufacturing made up a fifth of Hong Kong’s bank lending, and loans to the wholesale and retail industries made up another third. Today, those categories make up less than 10 percent combined.

Yet even as industry and real productivity declined, housing prices skyrocketed:

The city’s eye-popping land prices—the highest in the world per square foot of residential property—are the mirror image of its low tax rates. Alice Poon, an author and former employee of Sun Hung Kai Properties and Kerry Properties, two of the city’s leading property developers, calls this Hong Kong’s “hidden tax.”

Singapore owes much of its development to the legacy of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, the British administrator who established it in 1819, Lee Kwan Yew, its first prime minister and “father of Singapore,” and Goh Keng Swee, it’s finance minister at the time of independence.

Although none of the three seem to have been directly influenced by Henry George the man, they were influenced by his antecedents Adam Smith and David Ricardo, and in Yew’s case by Henry George’s followers in the form of the British Fabians. Despite having no direct connection to the man himself, Singapore is often cited as the closest approximation of a Georgist state anywhere on earth. This is because it ran on two key principles—low taxes on labor, trade, and industry, and an explicit state mandate to collect recurring land rent. The chief difference between Singapore and Hong Kong is that Singapore leaseholds come with a recurring ground rent charge that tracks the increasing value of land over time.

EDIT 11/14/2025: Apparently Singapore does not collect a recurring ground rent charge. They used to, in the historical period, but no longer in the modern day. I must have misinterpreted this following passage in Bird’s book:

Buyers of land leases paid a sum to the new governors of Singapore and an annual ground rent. “I have established a revenue without any tax whatever on the trade, which more than covers all civil disbursements, and which must annually increase in future years.” [Raffles] added. Henry George would not be born for another sixteen years, but the sentiment would surely have met his approval.

Lee Kwan Yew built upon this foundation in the wake of World War II:

“No private land-owner should benefit from development at public expense,” Lee argued. “I said I would introduce legislation which would help to ensure that increase in land values because of public development should benefit the community and not for the land-owner. Land is become a scarce commodity and with the mounting pressure on land at present, we must try to control land values for public purposes.”

Lee meant what he said, and in characteristic fashion rammed his will through. The Land Acquisition act of 1966 allowed the government to buy land at a discounted rate that deducted any increase in land value from the previous seven years that the state deemed associated with government expenditures. Landowners protested, but Yew got his way.

Once the land was in state hands, Lee pushed for a unique, regulated public-private homeownership system. The city-state has now achieved some of the highest rates of home ownership in the entire world, while at the same time keeping price-to-income ratios no higher than what one might expect in Tulsa, Oklahoma. To be fair, “ownership” in Singapore means a 99-year lease, not a perpetual title, and it comes with a recurring ground rent charge that approximates the effects of an LVT. Nevertheless, the results speak for themselves:

Singaporean economist Sock-Yong Phang, an expert in the city’s land-use policies, notes that 25 percent of Singapore’s housing wealth is owned by the bottom 50 percent of asset owners. In major financial centers like Hong Kong, London and New York, with homeownership rates of barely 50 percent or even lower, the share of housing wealth owned by the bottom 50 percent is effectively zero. Singapore’s system, by contrast, has allowed for extremely high rates of homeownership, but without turning homes into investments through which owners can easily get rich at the expense of future buyers.

EDIT 11/14/2025: Dr. Andrew Purves from University College London kindly shared this with me over email. “It was Erik Lorange, the Norwegian Town Planner who recommended land acquisition and subsequent sale of leases with an annual ground rent to the Singapore government in his 1962 report; but the ground rent element was not taken forward.” Mike himself had this to say in a follow-up email:

When it comes to the Board acquiring land from the government it all becomes a bit circular - the HDB actually buys the land (at a “fair market price” though I don’t really believe this to be the case, since the market is so managed and there’s often no other buyer) - so the land reserves held by the govt go down, its financial reserves and the NIRC that Andrew mentions go up. The government then offers a bunch of subsidies and grants to make sure everyone can afford the new apartments when they’re built, and since they’re so cheap the Board doesn’t recoup its expenditure, and receives a grant from the government to cover the shortfall. It’s all very circular I think, and it makes most sense if you think of the Board and the government as just the government. BUT I think this ends up approximating something LVT-like when you skim out all of the circuitous steps.

By aggressively disarming the Land Trap, Singapore managed to make housing actually affordable, which redirects investment money away from land speculation and towards things that actually grow the economy, like tools, materials, research, and workers. Modern Singapore has now surged ahead of its twin city:

While Hong Kong lags deep in the rankings when it comes to both exports in high-tech goods and income made from intellectual property rights, Singapore comes first and fifteenth respectively in the global rankings for each. The country has more than twice as many workers per capita focusing on research and development than Hong Kong. Singaporean companies and residents have filed between four thousand seven thousand patents each year over the last decade or so, compared to a few hundred per year in Hong Kong.

It’s true that Singapore simply bulldozed over landowner resistance, and that its political system is more authoritarian than Westerners are comfortable with, making Singapore an unlikely model for the West to copy directly. The People’s Republic of China, on the other hand, has no such qualms quashing dissent, so you’d think they’d be drawn to its success and eager to emulate it. Indeed, visiting Chinese politicians loved what they saw, catching “Singapore Fever” as they hyped up the city to their colleagues back home. In the end, however, it was Hong Kong, and not Singapore, that China modeled their land regime after:

Hong Kong became the proving ground for the way China treats land, housing and government finance. The conditions that have smothered Hong Kong’s innovative spirit and made it so economically unequal have been transmitted to the world’s second-largest economy too—without much thought for the consequences.

The results have not been great.

Bird asserts that China has gotten its land policies disastrously wrong, at great cost to its future growth prospects and overall stability as a nation. This is the case even if we put entirely aside all of Mao’s disastrous policies, what with the murder of landlords, collectivization of agriculture, cultural revolution, and famines. Reformers like Deng Xiaoping made many wise decisions that unlocked tremendous growth in the post-Mao era, but still made enough bad choices when it came to land policy that China ultimately fell into the morass that it faces today.

China’s particular problems with housing bubbles are surprising to me. According to Chinese Communism, getting ruined by financial speculation is supposed to be a problem particular to degenerate Western Capitalism. How could China, which severely represses the financial sector and owns all the land, fall into the Land Trap, if the Land Trap is caused by private financial speculation on land?

The reason is that China fell into all the same problems as Hong Kong, added several destructive innovations of its own, then deployed it all at massive, unprecedented scale.

In addition to the broken Hong Kong model, China’s central government made a sudden change to local tax policy. Originally, government was fairly decentralized, with local officials in charge of local tax revenues and local spending obligations. That changed in 1993 when the central government started appropriating large shares of local government revenues for itself, while the local spending mandates remained unchanged.

Local governments became desperate for alternate sources of revenue, but couldn’t raise new taxes because Beijing would just take a huge cut, and couldn’t take out loans or issue bonds because of banking restrictions. Officials eventually realized they could raise money with land lease sales, which wouldn’t count as “tax” revenue for Beijing could seize. Suddenly local governments were selling off land as fast as they could.

You’d think local officials might have second thoughts, because they would eventually run out of land and would then have no means left to finance their future for the next 99 years. Bird explained a second bad incentive to me over a phone conversation: top local Chinese officials aren’t lifers, and constantly hop from one province to another, seeking eventual posts in Beijing. Since leadership doesn’t stay around long, there’s less incentive for them to look out for an individual region’s long term stability.

This certainly explains why there was so much supply-side pressure to prop up land transactions. But what was fueling the demand side—who was eager to buy? In 1998 the central government enacted another market reform, allowing citizens to buy and hold private property in real estate for the first time. These “purchases” were still land leases, but this was a major departure from the previous, more explicitly communist, housing system. This unlocked a flood of Chinese citizen’s savings which quickly flowed into real estate.

Meanwhile, the central government went to great lengths to suppress all other forms of investment:

The Chinese government engaged in financial repression to direct the country’s savings towards its industrial champions. Interest rates on bank deposits were kept deliberately low to ensure the banks could offer low-interest loans for China’s prized state-owned enterprises. Though the Chinese economy was growing almost more rapidly than practically any other economy in the world, the returns on holding money in a bank were often negative, after accounting for inflation.

China also imposed strict capital controls to prevent citizens from investing their money in foreign markets like US stocks, leaving average citizens with nowhere to park their money other than real estate. Beijing wanted investment to flow to manly Chinese priorities like factories, cars, and high technology, not effete Western nonsense like cryptocurrency, financial derivatives, and social networking apps. The bitter irony is that by crushing every other form of investment as hard as it possibly could, but still leaving the door open for land, China somehow managed to out-West the West at ruinous financial speculation.

Bird then details for many pages how the massive Chinese real estate companies went bankrupt, one after another, as well as the bizarre after effects of sky-high prices. He notes that: “China’s housing bubble managed to produce some of the worst symptoms of a housing glut, and the worst symptoms of a housing shortage, all at the same time.”

House prices in China were (and still are) absolutely insane:

By the time the Chinese government finally decided to act against the real estate developers who had facilitated the boom, the average price-to-income ratio was 13.4 not just across the most expensive cities in the country, but across its fifty largest urban areas. Chinese house prices make those in San Francisco and London (with house price-to-income ratios of around 10 and 9.1 respectively in 2024) look cheap by comparison.

This is the point where one might rightly be skeptical of Bird’s mounting thesis. Sure, this all sounds bad, but plenty of China watchers have been proclaiming the Middle Kingdom’s impending doom for ages, and the fated crash keeps not happening. Evergrande, one of the most famous real estate mega-corps, went bust way back in 2021. If that was China’s Lehman brothers moment, why hasn’t the prophesied collapse yet arrived, now that it’s already 2025?

Mike addresses this head on. China did eventually decide to impose discipline on the housing sector, and the bubble is now slowly deflating. However, instead of ripping off the band-aid, China has apparently decided to delay the painful aspects of the recovery phase as long as possible:

If Beijing wants to prevent the bubble from bursting entirely, holding the housing market in a sort of suspended animation, it may well be able to do so. But that does not mean the government can hold back the financial tides without heavy cost. Even as enormous profits have been made in the land and real estate markets in China over the past three decades, the relentless boom means the financial and material resources have surged into the property market and away from other places. A growing stack of research by academics in China and abroad comes to an alarming conclusion: the astonishing excesses in China’s real estate market have seriously damaged the productive potential of the economy, across sectors and sometimes in very unusual ways.

Mike cites several researches that catalog the ongoing destruction and lost productivity caused by the Chinese housing bubble:

One piece of research by economists Harald Hau and Difei Ouyang shows that in cities where land has risen most rapidly in value, borrowing costs for small manufacturing companies have surged too. Capital constraints on banks limit how much they can lend in total, and mortgages—as in the West—are inevitably seen as a safer bet than riskier unsecured business loans. Across 172 of the cities the academics looked at, in the places where real estate prices increased most rapidly, the credit crunch for local businesses reduced corporate investment by 21 percent, total output by 36 percent, and overall productivity by 12 percent.

A paper from economist and IMF researcher Yu Shi in 2018 shows:

the most productive manufacturing companies in China have reduced their spending on research and development and their overall investment in their usual business when local real estate markets have boomed, moving instead into the land speculation game. Without the real estate boom, Yu estimates that productivity in the manufacturing sector between 1995 and 2010 would have been 0.5 percent stronger per year.

A loss of 0.5 percent per year may sound small at first, but consider that lost growth compounds every year, and you can see how much is lost over a 25 year period. Additionally, Beijing economists Lixing Li and Xiayu Wu showed how surging real estate prices discourage entrepreneurship:

While homeowners enjoy the surge in prices, young people who do not yet own a house are faced with the growing size of a potential mortgage to repay, and the fact that they need a home for any prospect of marriage. Between 2000 and 2010, the research notes that the rise in residential house prices averaged 9.4 percent, while the average rate of return made by Chinese companies was 5.6 percent.

China is now locked in a nasty trilemma.

On the one hand, it could let house prices fall to their natural levels. However, the Chinese social contract is basically “give up your freedoms and we will give you prosperity.” Cleaning out the rot in the housing market will take time, and also a lot of pain. That very pain, however, could risk social instability that threatens the regime itself.

On the second hand, it could try to re-inflate the bubble, artificially propping up house prices. If it does this, the Land Trap will continue to drain life out of the economy and steadily eat away at its future.

On the third hand, it could muddle through somewhere in the middle between those two choices, which seems to be Beijing’s chosen path. Or as Bird calls it, “protracted stagnation.”

Bird closes the book by saying that short of some new technology that effectively expands the frontier, the Land Trap can only be disarmed by striking at its core. He speaks sympathetically of Henry George and the Single Tax movement throughout, while unsparingly chronicling the movements’ historical political failings. He concludes by saying no easy fix in sight.

Nevertheless, his examples all paint a classic Georgist picture—uncollected land rent invites speculation, speculation drives up land prices and drives out investment, reliance on other taxes crushes productivity, which all leads to recession, stagnation, and decline.

The solution implied by Bird’s one successful example—Singapore—is also classically Georgist:

Collect the land rent

Encourage people to invest in actually productive things

Don’t artificially prop up land selling prices

Mike has done us two main favors in writing this book.

First, he has coined “The Land Trap” as a useful and catchy term to describe the problem. In naming the problem, we can see it clearly and direct appropriate attention towards it.

Secondly, he has detailed a solid case study in Singapore showing that the problem can be solved in at least one way. We can add to this our own example of the historical German colony in Qingdao, as well as other partial examples like the Pennsylvania split-rate experiments.

Going further, we can look beyond land value tax policies for even more evidence, such as my own state of Texas, which has low taxes on income and corporations, but high taxes on property. The portion of property tax that falls on buildings is bad because it inhibits building, but the portion that falls on land is good because it disarms the Land Trap. The state of California, which actively subsidizes land ownership through Prop 13, and simultaneously burdens its citizens down with additional taxes, serves a similar role to China in showing us what not to do. If we think of Georgism as a spectrum of policy choices rather than a single maximalist pole, we could plot US states on a line like this:

It’s hard to directly compare Asian countries with US states, but we might compare China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and historical Qingdao relative to each other:

The Land Trap is the diagnosis. The cure is Land Value Return, and the good news is that delivering it is both pragmatic and achievable:

Land value return is needed, pragmatic, and achievable

On September 26th, 2025, the Progress & Poverty Institute and the Center for Land Economics joined forces for our first of many “LVT Landscape LIVE” events where we update the community on what’s been happening nationwide in the world of LVT and related policies, including input from local officials actively running on this issue. Many people weren’t ab…