Nidhi Hegde, executive director of the American Economic Liberties Project, has a piece out titled “Anti-Monopoly Is the Path Forward,” part of a package in Democracy making the case that Democrats should continue the failed anti-neoliberalism crusade of the Biden years.

The most provocative thing that Hegde says in the article isn’t about antitrust policy or the Biden Administration, though — it’s about financial regulation under the Obama Administration. She argues that these topics are linked because (emphasis added):

The anti-monopoly movement came together as a response to the 2007-08 financial crisis and the mistakes the Obama Administration made in handling it. Opting for short-term stability over systemic change, Obama-era regulators let major banks off the hook for their criminal behavior despite widespread outrage from across the political spectrum.

This notion has become surprisingly mainstream over the past five years.

AELP was an influential player on Biden-era antitrust policy. Democracy itself hosted its second annual conference last week featuring lots of Biden economic policy appointees. David Dayen has acceded to the editorship of The American Prospect since pioneering this thesis. And I’ve often thought that what Hegde writes here on the record is, in a sense, correct, that lurking beneath the surface of some technical-sounding arguments about antitrust is this conviction that Obama failed to prosecute bankers for crimes that led to the financial crisis.

And that is really quite a remarkable thing to say.

As proponents of this anti-Obama conspiracy theory have moved closer to the mainstream of Democratic Party politics, Obama himself continues to be the most popular Democrat in the country, an in-demand speaker and surrogate every election cycle and the most accomplished progressive politician of recent generations. I know that a lot of people who are not particularly in the weeds on policy think I sound crazy when I talk about the extent to which diehard Obama-haters were steering the ship of state during the Biden Administration. But every once in a while, this kind of thing slips out.

So it’s worth actually asking: Is it factually true that the Obama administration deliberately tanked winnable criminal cases against major American banks?

The answer, of course, is no. But it’s hard to prove this kind of negative. And the accusation has been repeated enough that a writer can now casually drop it into a magazine article without being asked to provide any evidence for this nuclear-strength assertion.

Dodd-Frank was a big deal

I don’t want to spend too long rehashing ancient history, but one of the reasons that the Obama Administration was so consequential is that not only did they pass significant economic rescue measures and a major permanent expansion of the social safety net, they also enacted a major overhaul of America’s financial regulatory system.

This law, Dodd-Frank, was a huge political battle at the time, fought tooth and nail by America’s financial services industry. It was eventually enacted on a basically party line vote in the House with the backing of three moderate Republican senators to get it over the filibuster hurdle. The need to obtain 60 votes ended up limiting the bill in some respects relative to what I (or the then-president) would ideally have done. On the other hand, the filibuster-proof majority that enacted Dodd-Frank has also given it a fairly robust and enduring legacy. Various implementing regulations have been written and enforced differently across administrations, and in Trump’s first term, Congress (unwisely, in my opinion) raised the threshold for how large a bank needs to be before it is subjected to the highest level of regulatory scrutiny.

Still, whatever its shortcomings, Dodd-Frank was (and is) a very big deal.

It provides regulators with additional surveillance tools to understand what’s going on in the banking system, and it also requires banks to conduct themselves with more restraint and less risk. This last part is key. If a restaurant business manages its finances recklessly and goes bankrupt, that’s unfortunate but life moves on. But banks pose stability risks to the entire economy when they go bust. This is really important to understanding the whole debate about Obama-era policy, because the thing that got everyone so mad is that the whole economy was in the toilet. But it was definitely not against the law for banks to engage in riskier behavior pre-Dodd-Frank — that’s why there was a whole political debate about changing the law.

I bring Dodd-Frank up just to underscore how wild the theory that Obama was deliberately tanking criminal cases is.

All administrations make mistakes. I thought at the time that Obama-era Democrats were much too inflation-averse in their approach to fiscal policy and negotiations with congressional Republicans.1 But reasonable people can disagree about this kind of thing — Biden-era policymakers decided to err in the other direction and that turns out to have some downsides as well. The accusation that Hegde and others are making is essentially that Obama decided to engage in a huge, high-stakes legislative showdown with the banking industry over new post-crisis legislation that wasn’t actually needed because he could have just prosecuted banks under existing statutes. On some level, I think incredulity is the right response to this theory.

The laws have changed

What’s true is that the Savings & Loan bank failures of the 1980s resulted in a lot of criminal prosecutions, which reasonably raised the prospect that we’d see a lot of criminal prosecutions in the wake of an even larger set of bank failures.

But rather than positing an Obama-led conspiracy, consider that after Bear Stearns collapsed (and before Obama was inaugurated), two traders at the firm were arrested and prosecuted, only to be acquitted in the fall of 2009. The ruling was that despite various incriminating emails and Blackberry messages indicating that the traders’ private views of the situation were at odds with their external-facing communication, the government had not proved beyond a reasonable doubt that they were willfully lying about the securities at hand. To quote from the New York Times coverage, the evidentiary bar for winning a white collar criminal case was just very high:

“These acquittals provide a cautionary tale for white-collar investigations premised on facially ‘smoking gun’ e-mails,” said John Hueston, who prosecuted Enron’s former top executives, Jeffrey K. Skilling and Kenneth L. Lay. “The texting, twittering, BlackBerry-toting jurors of today understand that an e-mail capturing a concern, doubt or momentary distress does not reflect thought over time, much less a vetted public statement.”

Speaking of Skilling and Lay, despite Hueston’s efforts, the Supreme Court eventually overturned Skilling’s conviction on honest services fraud (Lay was already dead) in an opinion written by Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In a related move, the Supreme Court unanimously overturned a criminal conviction of the accounting firm Arthur Andersen in 2005.

Despite the failure of the Bear Stearns cases, the DOJ did eventually bring a case against a bond trader named Jesse Litvak that they felt they had even stronger evidence on. They won, had the conviction overturned, then won again, then had it overturned a second time. You don’t need to like the shifting judicial standards with regard to white collar crime, but you do need to acknowledge that there has been a real change since the 1980s. This is particularly notable in the political space, where former Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell got a conviction overturned. So did a New Jersey mayor. What’s striking about former Senator Bob Menendez’s corruption is that it was blatant enough for him to actually get convicted after having gotten off once.

One point that I would make about all these cases is that in our increasingly polarized climate, these were generally not divisive Supreme Court rulings. Republicans love white collar criminals, but progressive justices also voted for these rulings and the decisions were hailed by the ACLU, which has a pretty consistent soft on crime ethic.

It is, of course, true that the Obama administration had choices. They chose to follow the guidance of the courts in terms of greatly narrowing the scope of broadly worded fraud statutes. They could have tried their hand at prosecutions that were objectively unlikely to succeed. They could have tried to pick a huge political fight with the court system and criminal justice reform groups. I don’t think that either of those things would have been a good idea, but if someone wants to write an article taking the other side of the argument, it would be a reasonable thing to suggest. But this is a far cry from the charge that, “Obama-era regulators let major banks off the hook for their criminal behavior despite widespread outrage from across the political spectrum.” What happened is the courts became much more hostile to the practice of turning widespread outrage into criminal fraud prosecutions via the use of broadly worded statutes. That change in judicial doctrine is a much more parsimonious explanation of why things played out so differently from how they did in the wake of the S&L collapse.

Instead, a lot of political effort went into writing new laws and then writing new implementing rules that were narrowly tailored to addressing behavior that regulators saw as problematic.

It’s good to proceed from true, rather than false, premises

What does any of this have to do with “anti-monopoly” policy? I’m not entirely sure, because Hegde doesn’t fully spell out the relationship.

But one common thread between these two policy areas is the search for ways to be dramatic and left-wing that don’t involve the tedious work of assembling legislative coalitions.

I know that a lot of people got sick and tired during the Obama years of hearing about the need to strike bargains with the Blanche Lincolns and Kent Conrads of the world. And now that those types of senators are gone, they’re sick and tired of hearing from people like me that the real question facing Democrats is how to put Iowa and Alaska and Ohio and Texas and Florida and North Carolina in play. The idea that passing laws about taxes and the welfare state is relatively unimportant compared to wielding executive authority under existing legislation is tempting.

But it seems to me that to get there, you end up needing to say things that aren’t true.

The Obama administration didn’t give the banks legal impunity. They brought civil cases on a variety of grounds and reached settlements that secured various amounts of money for various things. But the upshot of all of that was less than earth-shattering. What really mattered was passing the Affordable Care Act and passing Dodd-Frank.

What didn’t quite work as well as it should have was a legislative agenda for rapidly restoring full employment. The gambit to secure comprehensive immigration reform came really close to working, but ultimately fell apart and left us empty handed. The idea that there was some route to progressive paradise that could be achieved purely through bold executive actions is, I think, just wrong. Most big concerns about the influence of tech companies on society are about the content — is ubiquitous streaming video making us lonely and wrecking our attention spans? — not about the size of the companies or the level of competition.

Of course, you see something very similar in DOGE. Why bother with the hard work of passing laws when you can just install Elon Musk and try to rule by fiat?

But what I think we are seeing with DOGE is that this works if, and only if, you are able to subvert the rule of law and ultimately set up some kind of extra-constitutional government. And maybe Trump can! Certainly, it seems easier to do that as a right-wing party that can count on some degree of sympathy from the business community than to do it from a left-wing perspective. But even for Trump, I am pretty skeptical. The bond market, certainly, does not appear to believe that whatever Trump is doing is actually going to generate the trillions in spending cuts that are needed to make the math work on Republican fiscal policy. Dealing with Congress and public opinion and normal politics is annoying and frustrating. But within the bounds of the law, at least, that’s what you have to do to govern.

Watching the political reaction to inflation in 2022-2023 has somewhat tempered my convictions about this, but it hasn’t totally changed my mind.

The debate over abundance liberalism unleashed by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book has, so far, been pretty lopsided. On one hand, you have the abundance liberals themselves, who walk on eggshells to avoid offending the sensibilities of people to their left, in the hope of building a big tent. On the other side, you have a collection of Warrenite progressives and Bernie-faction leftists who simply assume that the abundance liberals are just a bunch of deregulators, and excoriate them for being corporatists and ignoring the dangers of billionaires and oligarchy and such.

Many things frustrate me about this debate. One is that most of the progressive critics of the abundance idea appear not to have actually read Klein and Thompson’s book; they lazily assume it’s all about deregulation, when in fact Klein and Thompson spend more time calling for building up state capacity and the power of the bureaucracy. Another frustrating thing is that the progressive critics seem to assume that their preferred ideas — such as antitrust — are alternatives to abundance, when in fact they usually don’t conflict, and sometimes complement each other.

But what frustrates me most is that by insisting on degrowth over abundance, progressives are hurting themselves much more than they’re hurting any billionaires, oligarchs, or conservatives. Most development policy is set at the city and state level, not at the federal level. Which means by embracing degrowth, progressives are only stifling development in blue states and progressive cities — places like California and Massachusetts. Meanwhile, red states like Texas just keep growing, because progressives can’t tell them what to do.

There are many ways in which this process ends up hurting progressives. Degrowth means blue states lose population, pushing them out with high housing costs. Degrowth means progressive cities become dysfunctional, making life worse for their progressive residents. Degrowth discredits progressive policies at the national level, helping people like Donald Trump win the presidency and Congress.

Back in 2023, I wrote a post called “Blue states don’t build”, about how America’s more conservatively governed states (especially Texas) are better at building housing and green energy than their progressive counterparts (especially California). That post is, if anything, even more relevant today. Even as progressives revile abundance liberals as corporate stooges, degrowth policies are hamstringing progressive politics and progressive communities.

Anyway, here’s my post from 2023. If this isn’t a wake-up call for progressives to abandon degrowth and embrace abundance, I don’t know what would be.

Here’s some bad news for the Democratic Party:

This map shows the number of seats each state is forecast to gain or lose in the House of Representatives by 2030. As you can see, the states losing seats are pretty much all blue states, while the states gaining seats are pretty much all red states.

This is because House seats are reapportioned based on population changes. Blue states are losing seats because they are losing people relative to the U.S. average, while red states are gaining people relative to the average. Here, for example, are the population changes in California and New York (blue states) vs. Texas and Florida (red states) over the past two decades:

Some of this is due to differences in state fertility rates — the Plains states and parts of the South tend to have more kids — but the main driver is simply migration. Americans are moving from blue states to red states:

Why is this happening? It’s obviously not just about the weather, given the moves away from sunny California and into frigid Idaho and Montana. Conservatives will tend to blame the trends on high taxes and progressive social policies in the blue states. But housing costs are far more important, financially, than taxes for most of the people who move from place to place.

Blue states like California and New York have high housing costs in part because these states tend to house “superstar” industry clusters like Silicon Valley, Hollywood, and Wall Street. These clusters draw in high-earning knowledge workers and price out lower-income and middle-income people. But California is losing population at all income levels, with high earners actually more likely to leave. And more importantly, if they wanted, blue states could just build more houses for the lower-income and middle-income people, canceling out the effect of increased demand.

They don’t. With the exception of Washington state (which, you’ll notice, is not forecast to lose any Congressional seats!), blue states tend to be much more restrictive in terms of how much housing they build:

I’m not going to rehash the evidence that allowing more housing supply holds down housing costs. It does. California and New York are driving people out of the state by refusing to build enough housing, while Texas and Florida are welcoming new people with new cheap houses.

In fact, blue states’ failure to allow development is a pervasive feature of their political cultures. Housing scarcity doesn’t just cause population loss — it’s also the primary cause of the wave of homelessness that has swamped California and New York. Progressives’ professed concern for the unhoused is entirely undone by their refusal to allow the creation of new homes near where they live. Nor is housing the only thing that blue states fail to build — anti-development politics is preventing blue states from adopting solar and wind, while red states power ahead. And red states’ willingness to build new factories means that progressive industrial policy is actually benefitting them more.

If blue states are going to thrive in the 21st century, they need to relearn how to build, build, build.

Why red states are winning the green energy race

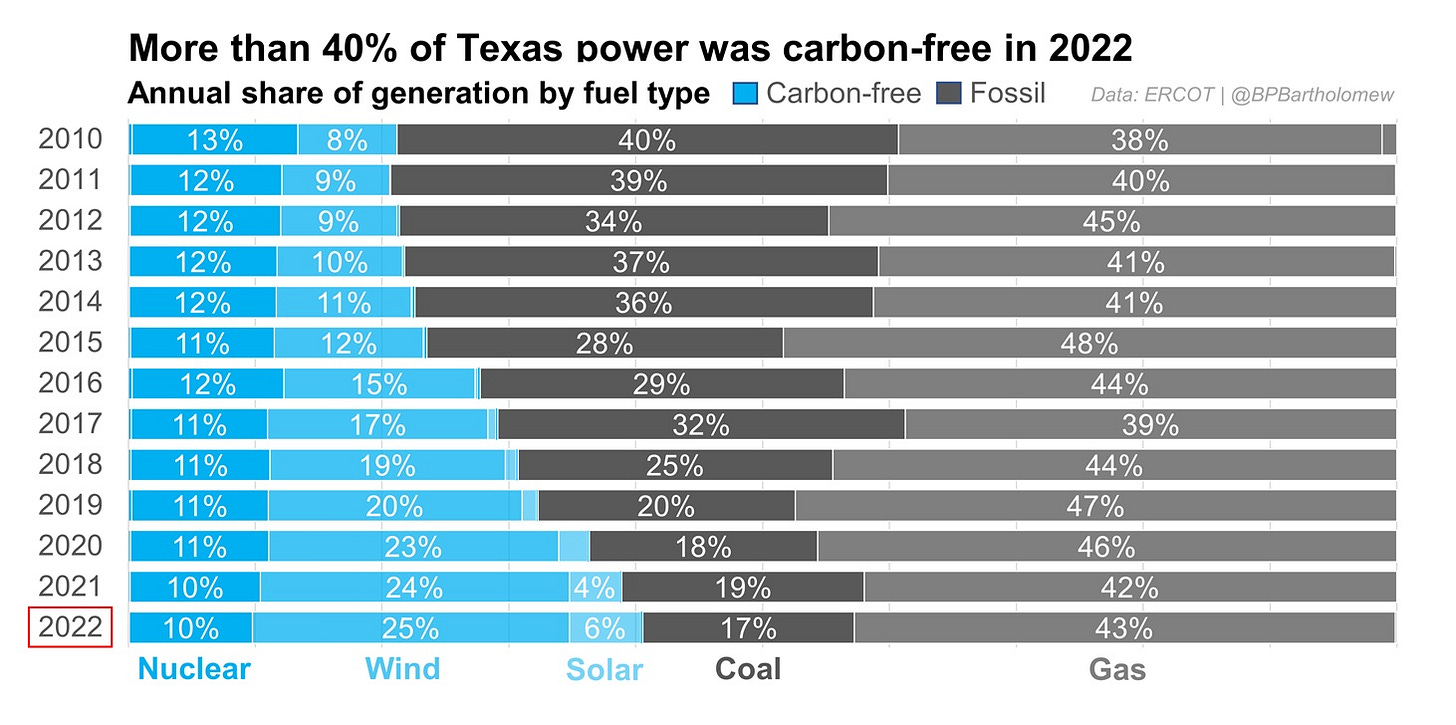

Texan politicians tend to bash renewable energy in their rhetoric. This is not surprising, given the strength of the oil and gas industry in the state. But if you look at what Texas is actually building, it’s clear that renewables are winning. Solar and wind now power 31% of the entire Texas electrical grid, and if you add nuclear, the proportion rises to 41%:

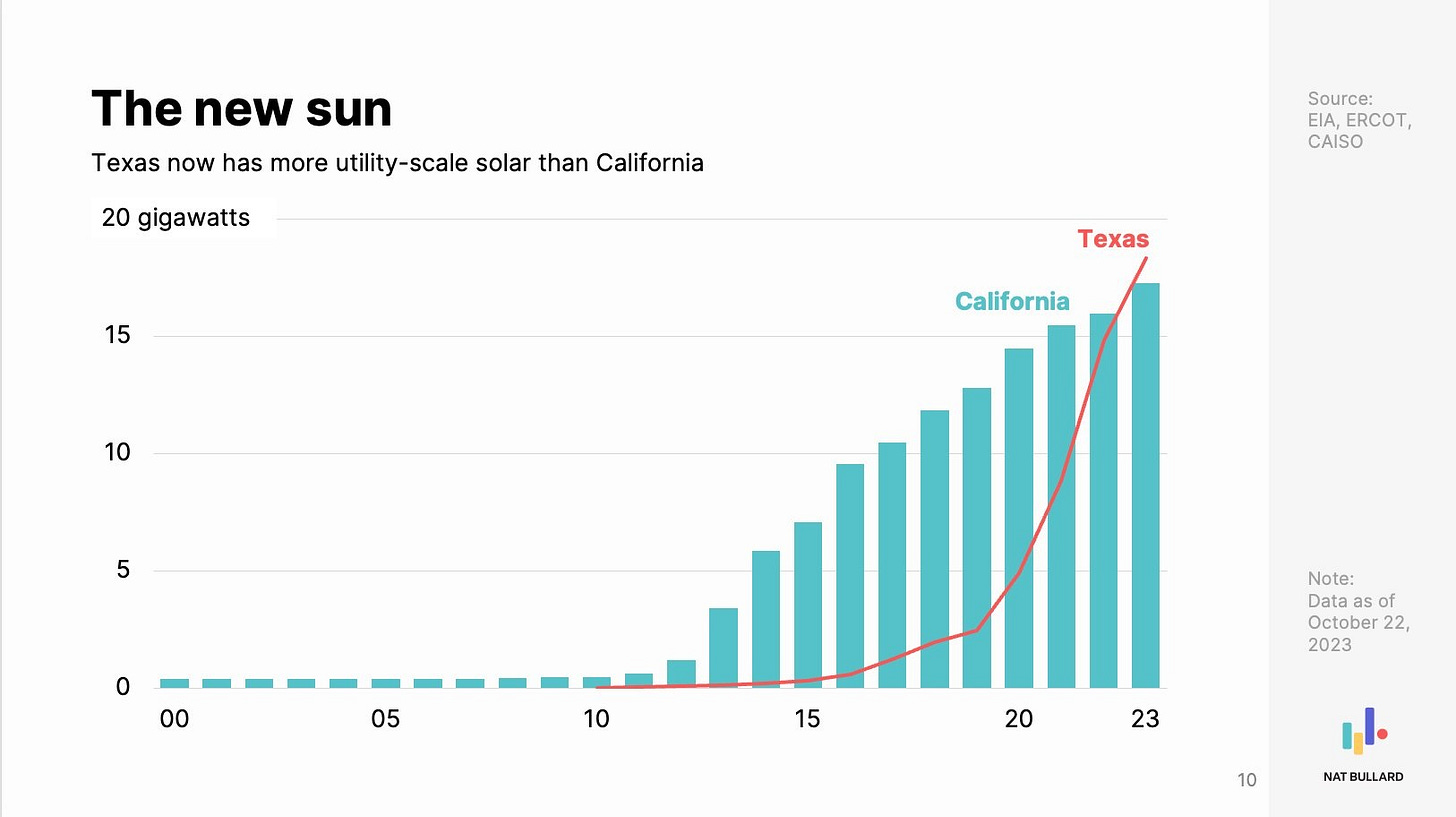

Wind dominates, but Texas has been building out solar incredibly rapidly — far more rapidly than California, for all of the latter’s policies to encourage the industry.

Florida is installing solar very rapidly as well, while New York State and Illinois, despite some plans to catch up, are still lagging severely.

Part of this is because southern states are sunnier. But this doesn’t explain why Texas is outpacing California. Nor does it explain why windy red states like Iowa, Oklahoma, and Kansas have built so much more wind energy than windy blue states like Minnesota, Illinois, and Michigan, despite having less land area and less total electricity demand.

Overall, this means that red states have been beating blue states in the renewables race for years now:

A 2019 top ten ranking of US states’ share of wind and solar power generation as a percentage of overall electricity consumption is dominated by red states…Red states held the top four slots, led by Kansas (53.7%), and followed by Iowa (53.4%), North Dakota (51.1%) and Oklahoma (45.4%).

Why is this happening? Why does Texas, a state dominated by pro-oil politics and conservative culture, have more solar power than sunny California? One answer that observers typically cite is land use permitting:

In Texas, solar permitting is uncomplicated. Connecting projects to the electric grid is straightforward. Then there’s cheap labor, homegrown energy expertise, plenty of sunshine and an anything-goes ethos. “There’s no ‘Mother, may I?’ here,” says Doug Lewin, who worked in the Texas Legislature on energy policy and now advises power companies. “In Texas, it’s just easier to get things done.”

In California, meanwhile, “citizen voice” in the form of anti-development lawsuits is allowing local NIMBYs to block solar projects. This NIMBYism is often facilitated by environmental laws like California’s CEQA, and local NIMBYs often ally with — or even masquerade as — conservation groups. NIMBYism exists in red states too, but strict land-use laws are much more common in blue states, and solar and (especially) wind take up a lot of land.

Another factor is tax policy. Red states tend to have lower taxes in general, but they also give tax incentives for energy projects that will ultimately return more than they cost in terms of tax revenue.

This is why blue states, for all their subsidies and mandates and other policies to promote green energy, are falling behind in the renewables race.

Blue states are swamped with homelessness because they don’t build housing

News stories are filled with apocalyptic tales of homelessness swamping American cities. Oddly, you never seem to hear these stories about Houston or Miami or Dallas or Atlanta. In fact, the homelessness problem in America is almost entirely concentrated in just two states: California and New York.

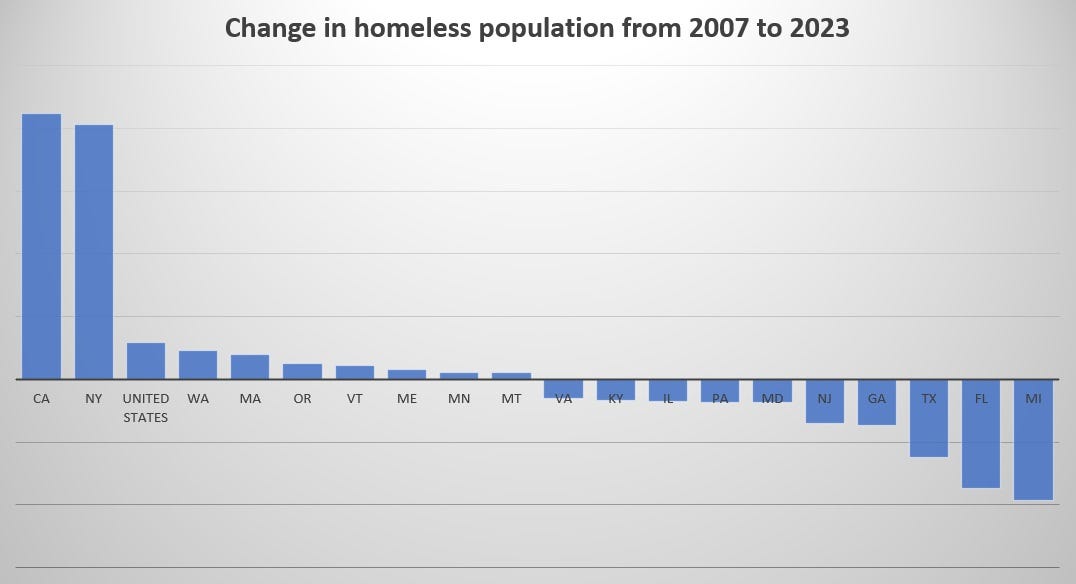

In my roundup this week I included a chart that showed that the U.S. other than California saw a big drop in homelessness since we started keeping statistics in 2007. But New York is just as bad (and in per capita terms, even worse). Here are the top ten and bottom ten states in terms of the change in homelessness from 2007 to 2023, along with the U.S. total:

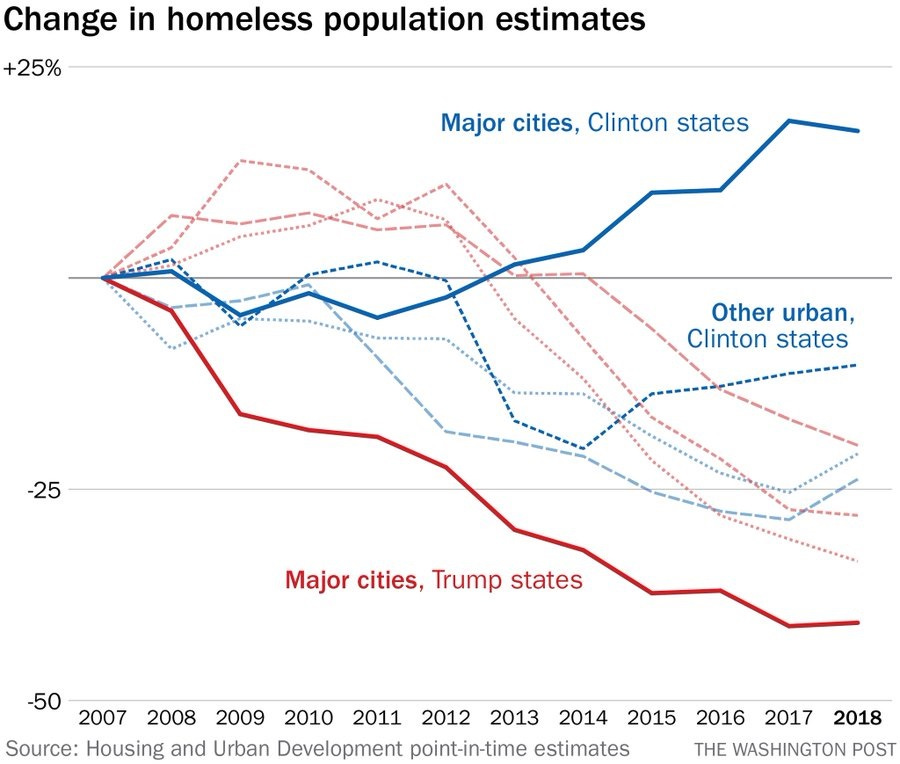

It’s not a perfect correlation, but you can clearly see a divide between the blue states and the red ones. The same pattern holds if you look at cities. Here’s an analysis by Philip Bump from 2020:

Is homelessness caused by high housing costs? Yes. Back in March, Aaron Carr wrote an excellent guest post for Noahpinion that brought together a large amount of data showing that housing costs were a far bigger factor than drug addiction, mental health, weather, or progressive policy when it came to explaining homelessness:

Plenty of other analyses tend to back this up. (Blaming California’s nice weather for an influx of homeless people is my favorite excuse, given that Texas and Florida have reduced homelessness massively, while snowy New York has seen a huge increase!)

The difference is obvious just from looking at cities in California and Texas. Austin has seen rents decline despite a big influx of tech workers, because they went on a home-building spree. Houston has had a massive population boom, but its inflation-adjusted house prices are lower than they were in the 1980s. Unsurprisingly, Los Angeles has 10 times as many homeless people as Houston, despite both cities being sunny and car-centric.

I very strongly recommend Ezra Klein’s recent podcast interview of Jerusalem Demsas. Both writers have been really excellent on covering housing issues, and their discussion strongly backs up what I’m saying.

I’m not going to claim that building housing is entirely without costs. Despite YIMBYs’ love for building taller buildings, urban sprawl is also generally part of the equation — and for red states, urban sprawl explains most of their housing construction advantage. Sprawl is not without its costs, especially in terms of destroying natural habitats — the kind of thing that NEPA and CEQA were intended to prevent. But the pendulum in blue states has simply swung too far toward “build absolutely nothing”, and the result is that they’re losing political clout, economic vitality, and the future of America to the red states.

Industrial policy isn’t helping the states that voted for it

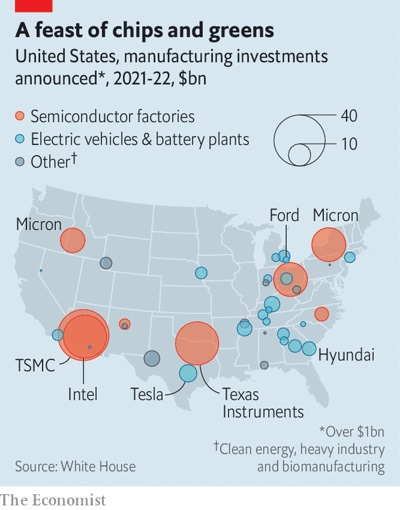

I should also mention one more thing that red states build more of: factories. Many analyses show that Biden’s industrial policies — the IRA for green energy and the CHIPS Act for semiconductors — will send a disproportionate amount of subsidies to red states. This is partly because Biden wants to court voters in those states, and partly because of cheaper labor costs, but mainly because those are the states that are willing to build more solar plants, transmission lines, and factories.

The red-state boom is a good thing. Red states tend to be poorer, so they need the boost more; it’s good to spread jobs out across the country instead of sending them all to traditional superstar clusters like San Francisco or Boston. But the fact that blue states largely resist building factories and energy infrastructure is holding back the nation’s economy as a whole. It makes little economic sense to have almost zero new manufacturing investments on either the West Coast or New England:

California, New York, and other blue states like Illinois and Massachusetts are, to put it mildly, important parts of the United States. The fact that they’ve been mired in stasis for decades is a big part of the reason the United States has become the Build-Nothing Country.

Yes, it’s important not to destroy natural habitats. Yes, it’s possible for some development projects to disrupt communities. But come on, folks. This has gone way too far. The hordes of people sleeping on the street, the steady drumbeat of people leaving the blue states, and the slowdown of decarbonization are all clear signs that the costs blue states’ love of stasis have become overwhelming. It’s time for them to learn how to build again.

Trump has proposed -- and depending on the time of day -- is actively planning to put large tariffs on aluminum imports (25% in the last version I saw). The implication is that there is some unfairness that has other countries producing a product we should be making domestically. Typically the argument is that the other governments are somehow subsidizing the product unfairly. Personally, I have never understood this argument -- as a US consumer I am perfectly happy to have taxpayers of another country subsidize my purchases. It turns out aluminum is a great example to look at because it is very clear why it is produced where it is.

First, let's look at where aluminum is produced, via wikipedia (perhaps taking Chinese reported production statistics with a grain of salt).

Some of this makes sense, but UAE? Bahrain?? Wtf? Let's explain:

Aluminum is produced pretty much the same way today as it was when the mass production process was first invented in the late 19th century -- using a LOT of electricity. Essentially, aluminum oxide from the raw bauxite ore is separated into pure aluminum and oxygen through an electrolysis process. I am not an expert, but estimates I have seen place electricity costs at 30-40% of the entire cost of aluminum. It takes something like 17,000 kWh of electricity to make one ton of aluminum. At some level you can think of a block of aluminum as a block of solid electricity**.

If you look at the top aluminum producers above, there is only a partial correlation with the top bauxite ore producers. That is because aluminum is generally not produced next to the bauxite mine but wherever the cheapest possible electricity can be found. The US historically produced a lot of aluminum, much of it in two places -- the Pacific Northwest and around Tennessee. You know why? Because these are the two largest areas of hydropower production, generally the cheapest source of electricity (its also why these were the two areas favored for early uranium separation). As US electricity costs have risen (and as we have actually reduced our total hydro power production under environmental pressure), aluminum production has moved to other countries.

Every one of the top six producers, excepting Canada, have electricity prices less than half those in the US. That is why Bahrain and UAE are on the list -- the are effectively converting their excess natural gas that might be wasted or flared to aluminum via electricity. Canada's electricity prices are also well under the US's though not as low as half, but Canada has a lot of very cheap hydropower in their eastern provinces and that keeps their aluminum industry viable.

It would be great to import 5-cent per kWh electricity from Bahrain, but there is no viable technological way to do that. So we do it the next best way -- we import cheap aluminum. This is a great example of why tariffs are absolute madness. Why would we possibly NOT want to take advantage of such fundamentally lower production costs in other countries for such a critical raw material?

The only possible political argument for doing so is that the government might wish to rebuild the US aluminum industry. But there is absolutely no way that is going to happen, for at least two reasons:

- Given the amount of electricity in the production costs of aluminum, to bring production to the US where electricity costs are more than 2x those of other producing countries would be to accept at least a 50% cost disadvantage, which is not going to be undone by a 25% tariff.

- But the more important point is this: No one in their right mind is going to invest based on the promise of tariffs that Trump himself changes almost daily and that will likely be politically undone long before any new plant is paid for, or even built. A new aluminum plant costs in the billions of dollars and it would be crazy to invest based on fleeting political promises. [OK, I freely admit that there do seem to be investors willing to make huge investments on the basis of what were likely fleeting political promises of government support -- solar, wind, EV's all come to mind. But "enticing investors to destroy capital" is not a very compelling reason to support subsidies and tariffs.]

If President Trump wants to rebuild the American aluminum industry, the best way would be to take actions that would free up regulations and mandates so that we could reduce the cost of electricity.

** Postscript: This is why aluminum is one of the very few items that it makes economic sense to recycle with current technology. Aluminum made from recycled scrap takes something like 1/20th the electricity of aluminum from the raw ore.

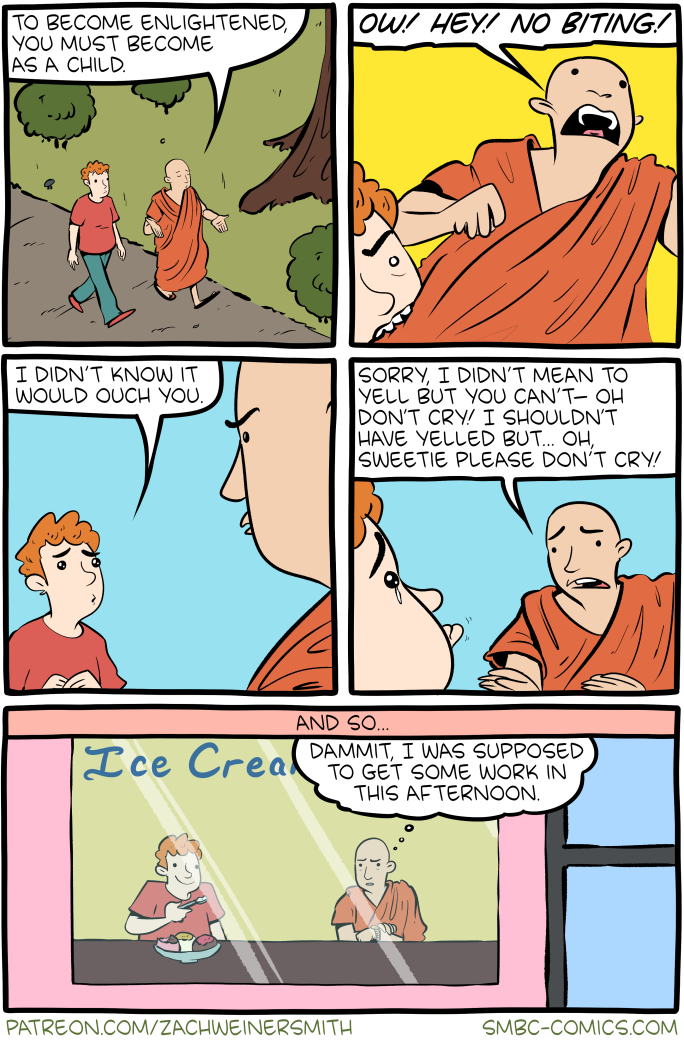

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

Ohh, you meant a romanticized well-behaved child in a permanent state of the kind of wonder actual children achieve three or four times a year.

Today's News:

Red Button mashing provided by SMBC RSS Plus. If you consume this comic through RSS, you may want to support Zach's Patreon for like a $1 or something at least especially since this is scraping the site deeper than provided.