| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about |

| ← previous | May 9th, 2025 | next |

May 9th, 2025: Don't forget to like and subscribe? I'd rather not forget to honk, shoo, and mimimi!! – Ryan | ||

| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about |

| ← previous | May 9th, 2025 | next |

May 9th, 2025: Don't forget to like and subscribe? I'd rather not forget to honk, shoo, and mimimi!! – Ryan | ||

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) was set to start enforcing the remaining provisions of its “click-to-cancel” rule on May 14th, requiring that subscriptions be as easy to cancel as to start. Now, the agency says it won’t enforce the rule until July 14th, as TechCrunch reports.

Also known as the Negative Option Rule, the big component of click-to-cancel is that it forbids companies from making customers jump through hoops that differ from the process to sign up for an account. If you can sign up online, you must be able to cancel online, too. As the FTC points out, the original May 14th deadline was already a deferral for that and related provisions.

The agency says it chose to push enforcement back even further after “a fresh assessment of the burdens that forcing compliance by this date would impose.” The FTC voted 3-0 for the delay, but as TechCrunch notes, two of a typical five commissioners were absent from the vote. That’s because they were illegally fired by Donald Trump in March.

Perhaps on the bright side for consumers, the FTC says that starting on the new deadline, “regulated entities must be in compliance with the whole of the Rule because the Commission will begin enforcing it.” However, it doesn’t rule out changing any of the regulation’s provisions, writing that it’s “open to amending the Rule” if enforcing it “exposes any problems.”

Policy changes often take years to show results. Even then, you may have to squint to see them.

And then there is congestion pricing in New York.

Almost immediately after the tolls went into effect Jan. 5 — charging most vehicles $9 to enter Manhattan from 60th Street south to the Battery — they began to alter traffic patterns, commuter behavior, transit service, even the sound of gridlock and the on-time arrival of school buses.

Evidence has mounted that the program so far is achieving its two main goals — reducing congestion and raising revenue for transit improvements — even as the federal government has ramped up pressure to halt it. In March, the tolls raised $45 million in net revenue, putting the program on track to generate roughly $500 million in its first year.

Congestion pricing was designed to finance more than $15 billion in critical transit upgrades. Those investments will take years. But the parallel changes at street level are already apparent.

Here’s what we know so far.

The idea was that many people, faced with a toll, would stop driving into the heart of Manhattan. So far, that appears to have happened.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority estimates that about 76,000 fewer vehicles per day entered the congestion zone in April than probably would have without the toll. That’s the equivalent of 2.3 million fewer cars for the month, or 12 percent fewer than would have been expected given historical traffic trends.

These numbers are based on the M.T.A.’s best guess of what would have happened without congestion pricing. (The cameras that are now counting cars entering the zone every day weren’t fully installed in January 2024, so we can’t compare exact car counts with this same time last year.)

The Port Authority, which separately controls the tunnels entering Manhattan from New Jersey, released initial data for January showing that 8 percent fewer cars entered through the Lincoln Tunnel, and 5 percent fewer through the Holland Tunnel, compared with January 2024. But the agency has not released data for February and March.

With fewer cars on the road, speeds are up.

Inside the congestion zone, as more workers returned to the office, average speeds had steadily declined since 2021, according to New York City Department of Transportation data that tracks the movement of vehicles licensed by the Taxi and Limousine Commission. Then starting in January of this year, that trend reversed.

An outside analysis from researchers at Stanford, Yale and Google found similar results. They looked at anonymized, aggregated data from trips taken with Google Maps and found that average traffic speeds inside the zone increased by 15 percent in the first two months of congestion pricing. That's compared with what the researchers estimate would have happened without the toll, given traffic trends in other cities.

Speed improvements have been greatest at the most gridlocked times, during the evening weekday peak.

The Google study found a similar pattern but an even larger effect in the program’s first two months, with speeds inside the congestion zone improving by more than 20 percent during weekday rush hours from 3 p.m. to 7 p.m.

M.T.A. bus speeds were also up January through March by about 3.2 percent compared with last year on the portions of local routes that run through the congestion zone. Gains have come on nearly every local route touching the zone.

Similar gains have come on express bus routes.

Some of the fastest improvements have been on local routes that cross the river on their way into the congestion zone. On route B39, which collects passengers at the Williamsburg Bridge Plaza in Brooklyn before entering the zone, speeds were up the first three months of the year by roughly 34 percent (a majority of the B39’s full route spans the bridge).

One major fear about congestion pricing is that it would improve traffic in the zone simply by pushing cars and congestion elsewhere. But so far, it appears that hasn’t happened.

According to Department of Transportation data, speeds in adjacent neighborhoods north of 60th Street in Manhattan and just across the river in Brooklyn and Queens, as well as in the rest of the city, have been flat or slightly faster than last year, depending on the time of day.

New Jersey Transit has not released bus speed data, limiting what we know about New Jersey commutes. But many M.T.A. express buses from Staten Island run through New Jersey and cross into Manhattan through the Lincoln Tunnel, sharing the same lanes used by many New Jersey buses and commuters.

Those M.T.A. bus routes went through the Lincoln Tunnel nearly 24 percent faster on average after congestion pricing went into effect.

The researchers using Google Maps data, who were able to analyze New Jersey commutes, found that congestion pricing increased speeds by about 8 percent for drivers making trips from Hudson and Bergen counties into the congestion zone.

The Google study also found consistently faster trips into the congestion zone — with speeds up by about 8 to 9 percent — whether drivers were coming from poorer or richer parts of the region.

That doesn’t address all the concerns of critics who warned that the toll would burden working-class drivers. But it does suggest that those drivers are sharing in the traffic benefits.

While the number of cars on the road is down, transit ridership is up, suggesting many commuters have switched.

From early January through mid-April, compared with the same time last year, ridership has increased on the bus and the subway for the M.T.A. It’s also up on the Long Island Rail Road, the Staten Island Railway and the Metro-North commuter lines that serve the northern suburbs and parts of Connecticut.

On the PATH commuter train that serves New Jersey commuters crossing the Hudson River, ridership is also up — by nearly 6 percent — in the first three months of the year compared with last year. New Jersey Transit, which runs a different rail and bus system into Manhattan, has not shared data, but stated it had “no evidence at this time that congestion pricing is having an appreciable impact on ridership.” (The policy is especially fraught in New Jersey, where officials are suing to stop congestion pricing in federal court.)

The Trump administration has seized on a number of high-profile crimes to paint mass transit as unsafe and a poor substitute for commuters who drive to the city. But on the subway, crime is dropping. In the first three months of 2025, criminal offenses in the subway fell to the second-lowest level in 27 years, with an 18 percent drop in major crime categories, police data shows.

Yellow taxi rides starting or ending in the congestion zone are up this year — there were about eight million trips across the first three months of the year, compared with about seven million in the same period last year.

Taxi passengers on routes that touch the zone pay an additional 75 cents per ride (those riding in for-hire vehicles, like Uber, pay $1.50). Many in the taxi industry worried that an added cost to fares would discourage riders and further harm an industry that’s been losing business for years. So far, that hasn’t happened.

It’s less clear that people are switching to biking. According to Citi Bike, ridership in the bike-sharing program through April 20 is up similarly both inside the congestion zone and citywide, 8 to 9 percent, compared with last year. But Citi Bike has expanded the network over time, making direct trip comparisons with earlier years imperfect.

The Department of Transportation also maintains some bike counters inside the congestion zone that count cyclists on personal bikes and Citi Bikes. Those counters show a very slight decline in trips compared with last year, while counters outside the congestion zone show a small bump in trips. Biking is also more subject to weather, and this past winter was especially cold.

In short, it’s probably too soon to say much about the effects of congestion pricing on biking.

With fewer cars on the road in the congestion zone, there have been fewer car crashes — and fewer resulting injuries. Crashes in the zone that resulted in injuries are down 14 percent this year through April 22, compared with the same period last year, according to police reports detailing motor vehicle collisions. The total number of people injured in crashes (with multiple people sometimes injured in a single crash) declined 15 percent.

Crashes and injuries are also down citywide outside the congestion zone, but by less, suggesting that the tolls could be a factor in the difference.

The story here may largely be about fewer cars creating fewer opportunities for collision. But Philip Miatkowski, senior director for research and policy at Transportation Alternatives, said that less congestion may also be increasing safety in other ways, like less double-parking and blocked intersections, or less road rage.

Data on parking violations suggests that certain types of risky driver behavior are declining. Violations issued within the congestion zone — for infractions like double-parking or parking in no-parking zones — were down nearly 4 percent from January through mid-April compared with last year. Over this time, there was a small increase in violations in the rest of Manhattan.

Vehicle-related noise complaints to the city’s 311 portal dropped by nearly half in the zone from 2024 to 2025. Similar car-related complaints also fell outside the zone, but not as sharply.

The city’s Department of Environmental Protection also operates two noise cameras inside the congestion zone. They detect noises greater than 85 decibels and, like a red-light camera, record the offending vehicle. Between Jan. 5 and April 4 of 2024, the department issued 27 horn-honking summonses. Over that time this year, it issued six, with another eight pending.

Average travel times for the Fire Department’s responses to fires inside the congestion zone dropped by about 3 percent in January through March of this year compared with the same period last year, according to Fire Department dispatch data. These times rose by less than 1 percent in the rest of New York.

It’s probably too early to tell whether the speedup inside the zone is the result of congestion pricing. Travel times can fluctuate year to year, and Fire Department officials cautioned that congestion pricing was only one possible factor.

Average travel times for ambulances had been steadily increasing since the pandemic, according to emergency service dispatch data. Those ambulance times rose again this year, but at a slower rate inside the congestion zone than elsewhere.

One school bus company, NYC School Bus Umbrella Services (NYCSBUS), has found that, compared with last year, the share of buses arriving at schools late has dropped more inside the congestion zone than outside it.

The company calculates that those reduced delays inside the zone have meant that bused students receive more than 30 additional minutes of instruction time per week on average.

NYCSBUS contracts with the city to serve about 10 percent of New York’s bus routes for school-aged kids, so its numbers don’t cover every school bus inside the congestion zone but offer a good sample.

Commuters care a lot about a metric that’s related to speed but distinct from it: Does the bus come when the schedule says it will?

More bus routes in the congestion zone are now running without delays, according to M.T.A. data. Bus delays have declined citywide, but the improvement has been greater within the zone.

Critics have argued that the toll would scare off tourists and hurt local businesses. So far, there’s not much evidence of that, even as some businesses report signs that declining international tourism and tariffs are starting to pinch.

In March, just over 50 million people visited business districts inside the congestion zone, or 3.2 percent more than in the same period last year, according to the New York City Economic Development Corporation (its estimate tries to exclude people who work or live in the area).

And according to the Times Square Alliance, the number of pedestrian visitors to Times Square through April 22 this year was almost identical — about 21.5 million people — to the number in the same period last year.

Broadway theater capacity is essentially flat compared with last year, after accounting for the increased number of shows this year.

Online restaurant reservations through the platform Open Table are up by about 7 percent in the congestion zone through April 22 compared with last year. That’s similar to the trend citywide, according to the company.

And just to take a different kind of measure, The New York Times visited 40 storefronts on a stretch of Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village to gauge how businesses felt about congestion pricing. People working in four of those businesses said the change had been positive, 10 said it had been negative — and 25 said it had had no impact.

These are just slices of the Manhattan economy, and it’s not hard to find individual business owners who feel things are worse because of congestion pricing. But those effects don’t seem to be showing up yet at scale.

Supporters of congestion pricing said it would also create environmental benefits, with fewer polluting cars on the road (and idling in gridlock or circling for parking).

The New York City health department’s readings of PM2.5, one air quality measure, improved citywide the first three months of this year compared with the same period in 2024. The improvement was more pronounced within the congestion zone, but it’s too early to attribute that to the program, or to know if that’s a lasting pattern, experts said.

If a downward trend in emissions showed up over the long term, it would mirror what happened in other cities after they put in congestion pricing. In London, rates of health problems aggravated by car pollution, like asthma, declined.

Critics of congestion pricing have warned that the tolls could harm lower-income commuters who lack access to transit. In response, the M.T.A. has carved out a 50 percent discount on peak tolls for drivers who make less than $50,000 a year. Some drivers can also apply for a tax credit.

But if those workers still feel they can’t afford to commute to the congestion zone, they may over time change jobs or face narrower job prospects. It will take time to track these changes, which could also be influenced by a worsening economic outlook.

In other ways, lower-income workers, who are more likely to use mass transit, stand to benefit from bus and rail investments that will be financed by the toll revenue. Some of the improvements, including new elevators and a more reliable signal system in the subway, are already underway.

Congestion pricing was unpopular in opinion polling just before it started. But its backers expected that it would grow more popular as people saw the benefits.

It’s still early to say that for sure. Several pollsters have surveyed the public about congestion pricing, but without repeating the same question across multiple surveys. That makes it harder to track changes in opinion. Some early signs, however, suggest the program is growing more popular (or, at least, that many New Yorkers don’t like President Trump’s intervention).

A Siena College poll in December, for example, found that only 32 percent of New York City voters supported the program (29 percent statewide). But by March, 42 percent said it should remain in place (compared with 33 percent statewide). Most recently, in early April, a Marist poll also found that 42 percent of city voters want the program to stay — still not a majority, but perhaps getting closer.

For years, I’ve been calling for the U.S. to promote manufacturing. When Americans started getting excited about reindustrialization, I cheered. I was a big supporter of Joe Biden’s industrial policy, and I even praised Donald Trump for smashing the pro-free-trade consensus in his first term.

Trump’s tariffs haven’t changed my mind about any of that. Yes, the tariffs are a disaster. But they’re not a disaster because they promote manufacturing; indeed, they are deindustrializing America as we speak, by destroying American manufacturers’ ability to leverage supply chains and export markets. When America has finally realized the futility of Trump’s approach, it will be time to turn once again to the task of reindustrialization — in fact, that task will be even more urgent, given the damage that Trump will have done.

And yet at the same time, I think there’s a misguided narrative about globalization, manufacturing, and the American middle class that has taken hold across much of society. The story goes something like this:

In the 1950s and 1960s, America was a smokestack economy. Unionized factory jobs built a broad-based middle class, and we made everything we needed for ourselves. Then we opened up our country to trade and globalization, and things started going downhill. Wages stagnated due to foreign competition, and good manufacturing jobs were shipped overseas. American cities hollowed out, and we became a nation of winners and losers. The college-educated upper middle class thrived in their professional jobs, while regular Americans were forced to fall back on low-wage service work. Eventually the rage of the dispossessed working class boiled over, resulting in the election of Donald Trump.

You can see this narrative at work in Joe Nocera’s recent much-discussed post in the Free Press:

No one anymore, on the left or the right, denies that globalization has fractured the U.S., both economically and socially. It has hollowed out once-prosperous regions like the furniture-making areas of North Carolina and the auto manufacturing towns of the Midwest. It has been a driver of income inequality…Trump owes much of his political success to the fury that these realities aroused in working-class Americans.

“My dad ran factories in the Detroit supply-chain orbit,” Financial Times columnist Rana Foroohar told me recently. “In the 1990s, the factories started shutting down. And when I would go home in the 2000s, half of my high-school classmates were on opioids.” She added, “The economic theories didn’t connect with the real world.”

Which raises an obvious question: Why did so many economists, policymakers, and journalists like me refuse to acknowledge the problems with neoliberalism for so long? Why were we so quick to label anyone who even flirted with the idea that maybe the U.S. should be protecting its industrial base, just as other countries did, as a Pat Buchanan-like fool?

One big reason was the most basic one: It meant low prices. Companies could keep their costs low by using China’s (and Mexico’s) comparative advantage: cheap labor. At the same time, companies like Walmart and Costco could buy goods directly from Chinese manufacturers, which invariably had lower prices than comparable American goods.

And you can see the narrative at work in a recent series of tweets by Talmon Joseph Smith:

Like all such narratives, this one consists of layers of myth wrapped around a core of truth. But not all grand economic narratives are created equal — in this case, the layers of myth are thick and juicy, while the core of truth is thin and brittle. Everyone knows about the China Shock paper and the collapse of manufacturing employment by about 3 million in the 2000s. That’s the core of the story, and it’s very real. But there are a lot of big important economic facts that place that story in perspective, which most of the people talking about this topic seem not to know.

Ultimately, the trade-driven collapse in manufacturing was only a small part of the economic story of America over the last half century.

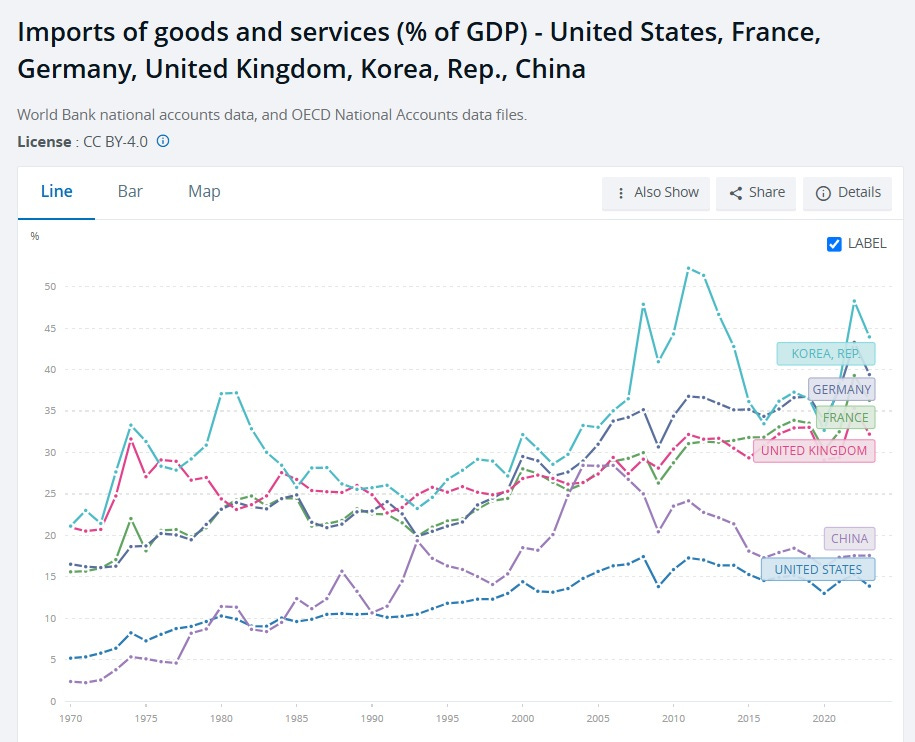

Pundits and politicians alike talk incessantly about the flood of cheap Chinese goods into America. But overall, this is a small percent of what we buy. The U.S. is actually an unusually closed-off economy; as a fraction of GDP, imports are much lower than in most rich countries, and lower even than China:

Trade deficits are an even smaller amount of GDP. U.S. imports of manufactured goods minus exports are equal to about 4% of GDP per year. Our trade deficit with China is about 1% of GDP.

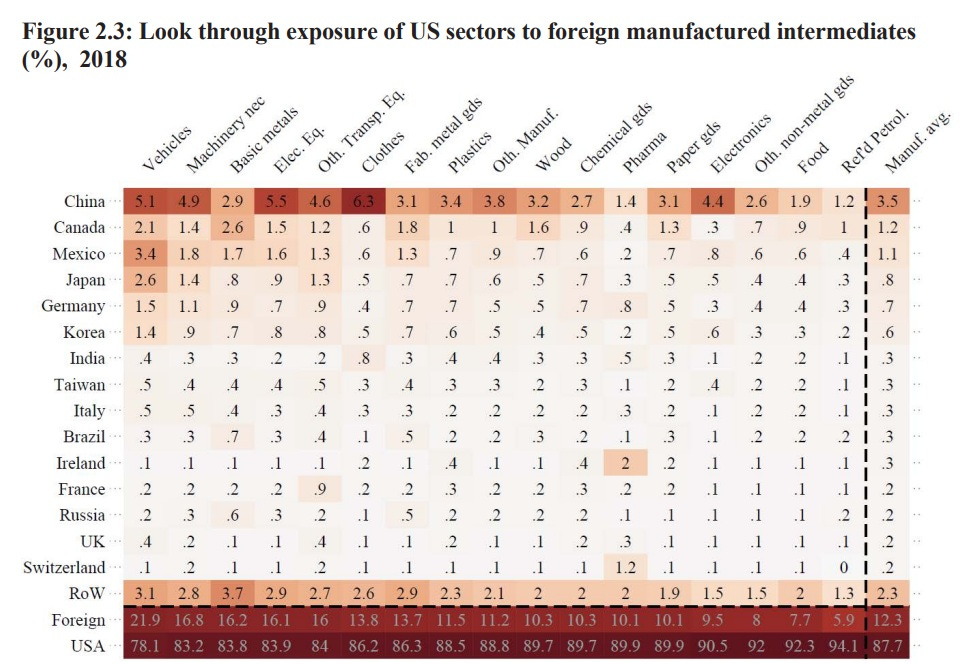

In terms of imported components, America manufactures most of what it uses in production. China’s exports to the U.S. are actually more likely to be intermediate goods rather than the consumer goods we see on the shelves of Wal-Mart — another thing the typical narrative misses. But even so, China makes only about 3.5% of the intermediate goods that American manufacturers need:

So if we eliminated trade deficits, would it reindustrialize America? Even assuming that we replaced the imports 1-for-1 with domestically made goods, the impact on manufacturing’s share of U.S. GDP would be fairly modest. Here’s Paul Krugman:

Last year the U.S. ran a manufactures trade deficit of around 4 percent of GDP. Suppose we assume that this deficit subtracted an equal amount from spending on U.S. manufactured goods. In that case what would happen if we somehow eliminated that deficit?

Well, it would raise the share of manufacturing in GDP — currently 10 percent — by less than 4 percentage points, because manufacturing firms buy a lot of services. A rough estimate is that manufacturing value-added would rise by around 60 percent of the change in sales, or 2.5 percentage points, implying that the manufacturing sector would be around a quarter larger than it is.

So even under the optimal scenario, if we totally eliminated the U.S. trade deficit, manufacturing would go from 10% of U.S. GDP to 12.5% — about the same as its share in 2007, and still far less than Germany, Japan, or China:

You can also see from this chart that other countries haven’t necessarily done an amazing job of protecting their industrial bases, as Nocera claimed; the manufacturing share of GDP is drifting down everywhere.

And this chart is also a hint that trade deficits and manufacturing aren’t as tightly linked as most people seem to think. France has become steadily less manufacturing-intensive since 1960, despite the fact that it historically had very balanced trade, and even ran big trade surpluses in the 90s and 00s. Meanwhile, out of all the countries on the chart, Japan has done the best job of preserving its manufacturing share since 2010, despite running a trade deficit over that time period.

So while we tend to focus a lot on the impact of trade on U.S. manufacturing, the truth is that there are much bigger forces at work there. Most of what the U.S. consumes is made here, and most of what the U.S. produces is consumed here, and eliminating trade deficits wouldn’t change either of those basic facts.

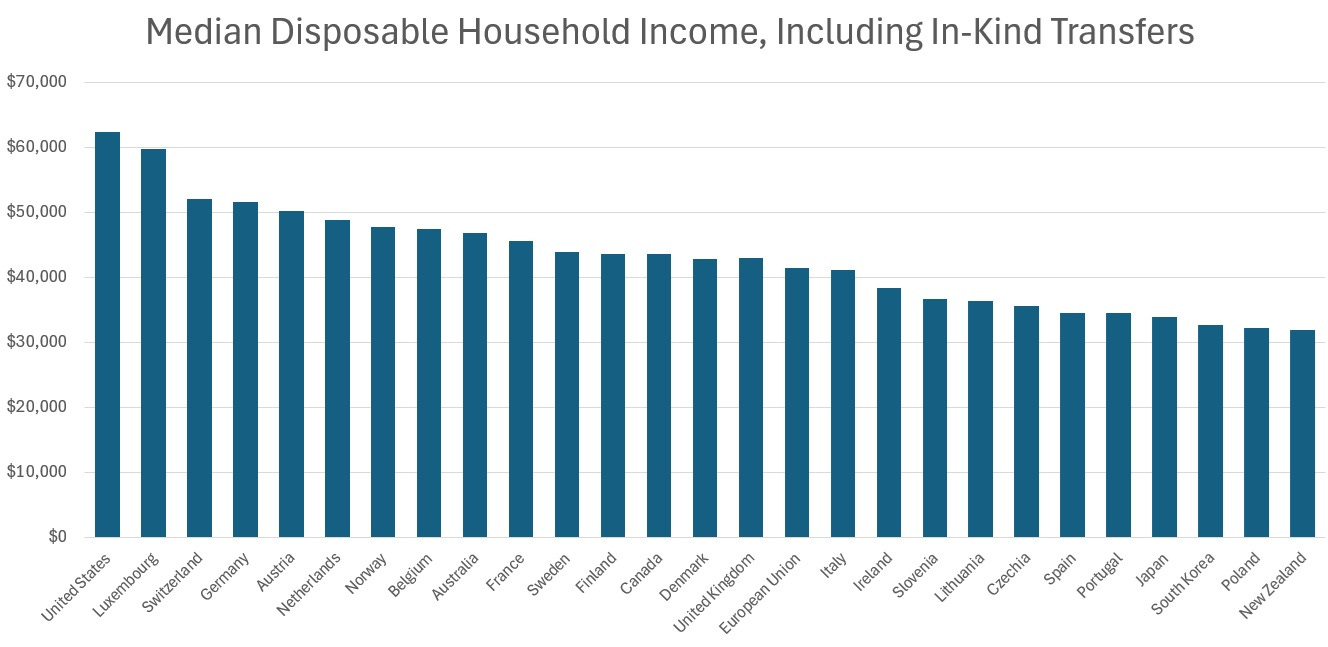

Americans, as a people, are startlingly rich. This isn’t just true because a few very rich people pull up the average. If you take median disposable household income, the U.S. comes out way ahead of the pack:

Note that this includes taxes and transfers, including in-kind transfers like government-provided health care.

Other countries may have protected their manufacturing sectors, but middle-class Americans are richer than the middle classes in other countries.

And middle-class Americans’ income has not been stagnant over the years. Here’s real median personal income, which isn’t affected by the shift to two-earner families:

This is an increase of 50% since the early 70s. I wish it had been more, of course, and it has its ups and downs, but 50% is nothing to sneeze at.

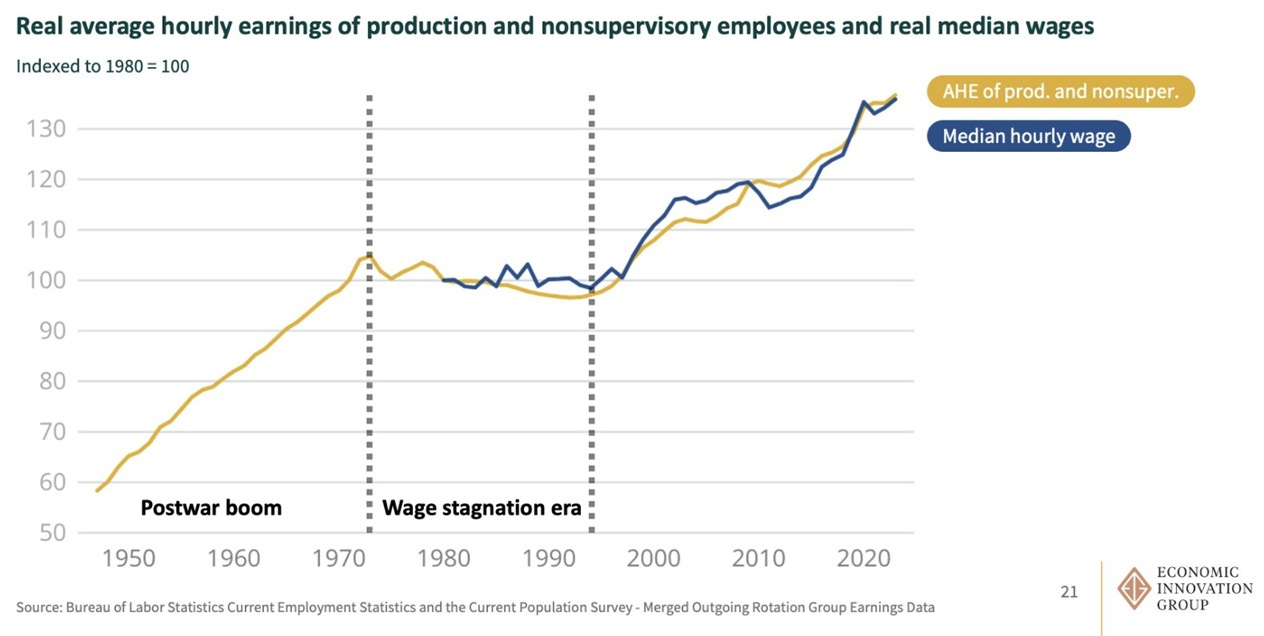

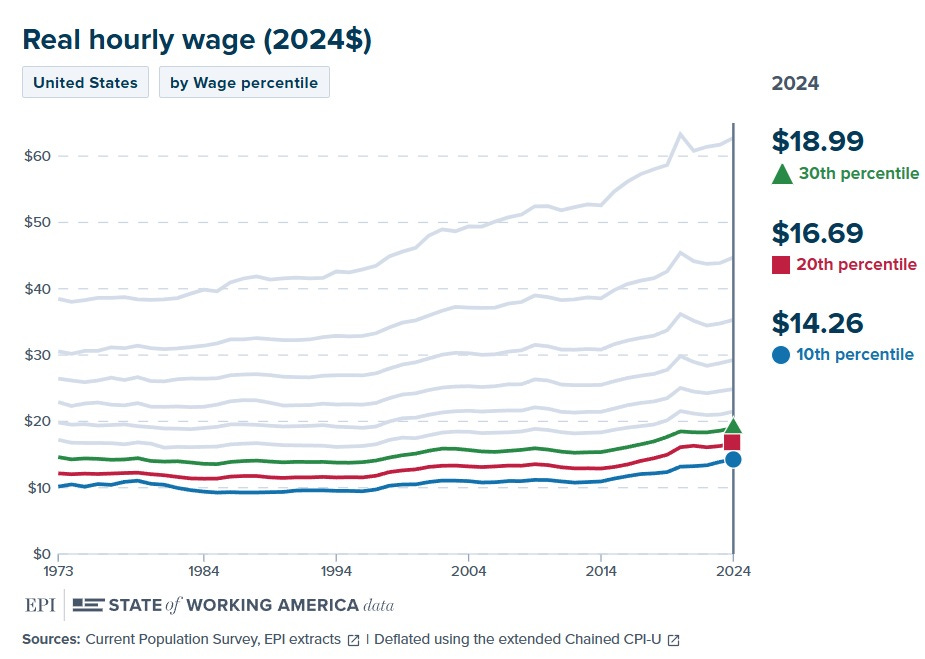

As for middle-class wages, they’ve grown less than incomes, since some of the increased income has been in the form of corporate benefits (health care, retirement accounts), investment income, and government benefits. But they have still grown:

Wage growth has resumed since the mid-1990s, despite increasing trade deficits. Note that the China Shock, which threw millions of manufacturing workers out of their jobs, utterly failed to stop wages from resuming their upward climb. Wage stagnation and hyperglobalization just don’t line up, timing-wise. Jason Furman has another good chart that shows this very clearly:

A lot of commentators have gotten so used to the idea that incomes are stagnant that they have trouble believing this data is correct. But as Adam Ozimek points out, the Economic Policy Institute — a pro-union think tank that frequently complains that wages are too low — chooses a very similar measure for median wages. EPI writes that wages “have not been stagnant”, but “have…been suppressed”.

And when we look at the lower percentiles of the wage distribution — the working class and the poor — we see that they’ve grown even more strongly, by over 40% since 1996:

A $4/hr. raise (adjusted for inflation) might not sound like a big deal, but for a poor person it’s pretty huge.

Of course, as Autor et al. show in their famous “China Shock” paper, the harms from Chinese import competition were concentrated among a few workers in a few regions. 2 million workers were only 1.5% of the U.S. workforce at the time, but for that 1.5%, being thrown out of good manufacturing jobs was a heavy blow.

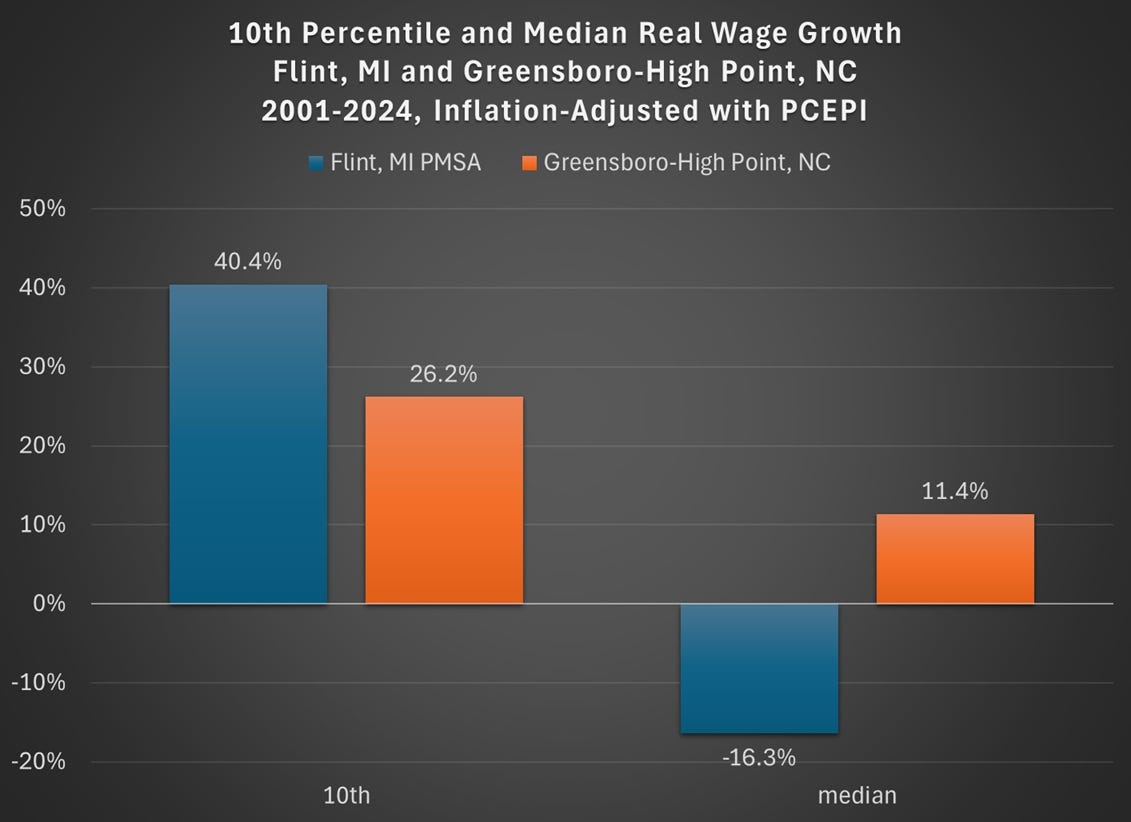

But even in those unlucky regions, the negative effects don’t look to have been permanent. Jeremy Horpedahl points out that wages for the poor in Flint, Michigan and Greensboro, North Carolina — two areas that Nocera claims were “hollowed out” — have actually increased, while middle-class wages have risen in the latter:

And when we look at median income, the two areas look like they’ve recovered their economic health over the last decade:

(Nor is this a composition effect from people moving out; Flint’s population has held roughly steady, while Greensboro’s population has continued to increase smoothly.)

How are the American middle class and working class prospering, if the good manufacturing jobs of yesteryear are all gone? Talmon Joseph Smith scoffs at “service economy jobs”, and Autor et al. find that manufacturing workers displaced by Chinese imports often took crappier, lower-paid jobs in the service sector.

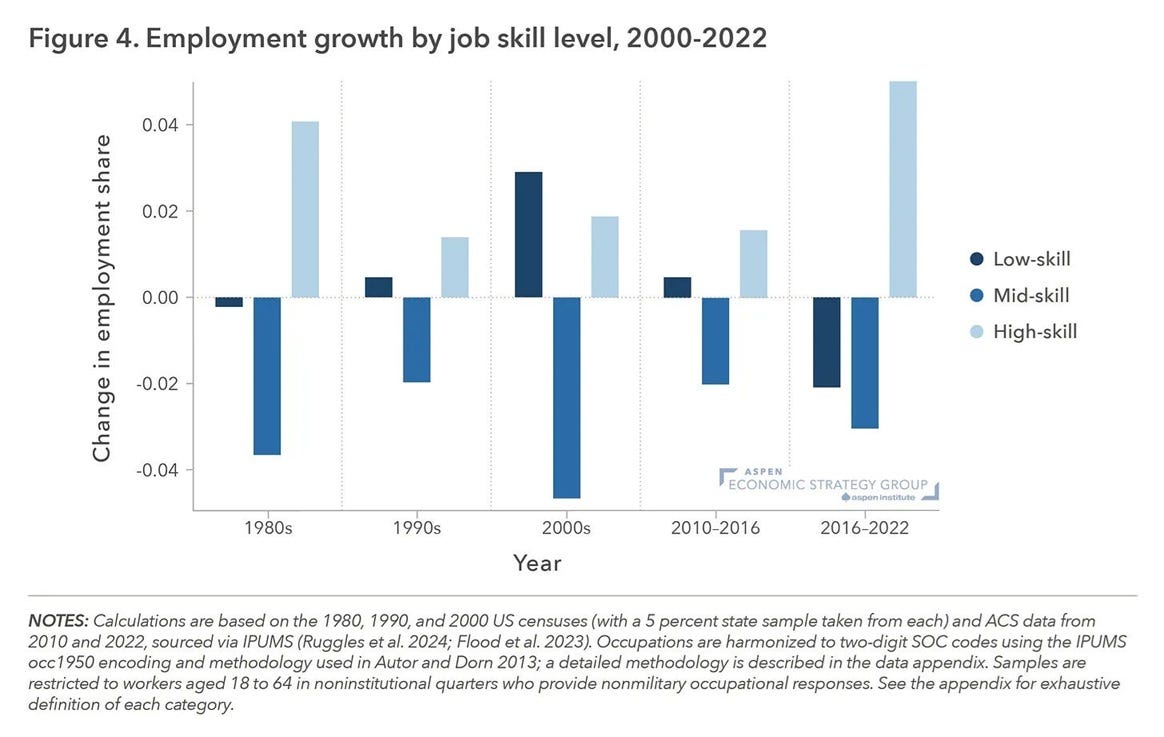

But that describes the 2000s. The 2010s and 2020s have been very different. Deming et al. (2024) show that over the last 15 years, the boom in low-skilled service-sector jobs has gone into reverse, and Americans are instead flooding into higher-skilled professional service jobs:

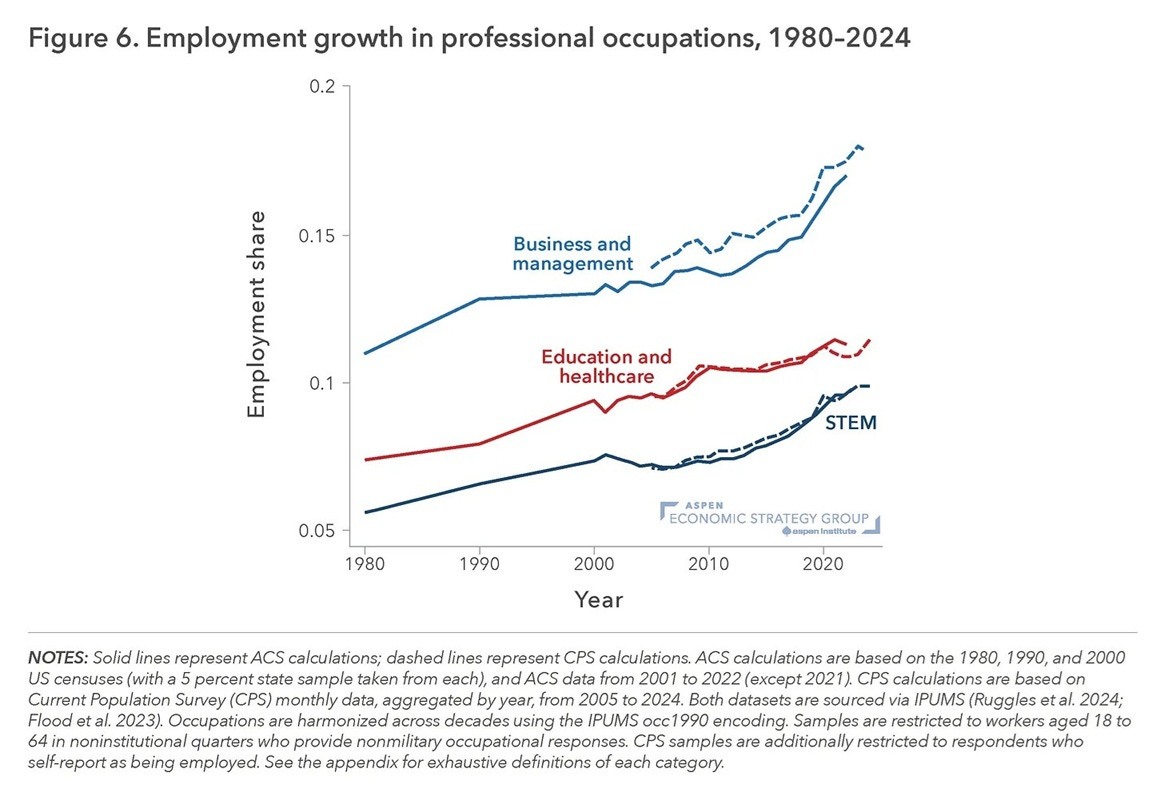

“Go to college” turns out to have been good advice. The boom jobs of the new era are in things like management, STEM, education, and health care:

It took a couple decades, but we’re finding that Bill Clinton was right — the average American is smart and competent enough to do knowledge work. And it’s being reflected in wages and incomes.

Now, none of this is to say that manufacturing is unimportant. It’s important for national defense, obviously. I also think it’s important for building a balanced, well-rounded economy — adding high-tech manufacturing on top of America’s knowledge industries would make us even richer, and would help us pump up exports and take advantage of multiplier effects. Manufacturing is also ripe for a productivity boom after decades of stagnation.

But the master narrative of protectionism is simply much more myth than fact. Yes, Chinese import competition hurt America a bit in the 2000s. But overall, globalization and trade deficits are not the main reason that manufacturing’s role in the U.S. economy has shrunk. Nor has globalization hollowed out the middle class — because in fact, the middle class has not been hollowed out.

Once we accept that this common protectionist narrative is deeply flawed, we can begin to think more clearly about trade policy, industrial policy, and a bunch of other things.

Welcome back to “One First,” an (increasingly frequent) newsletter that aims to make the U.S. Supreme Court more accessible to all of us. If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider becoming one (and, if you already are, I hope you’ll consider upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit):

I was going to wait until Monday’s regular issue to note the sad news out of the Supreme Court on Friday (that retired Justice David Souter passed away Thursday at the age of 85). But then Stephen Miller went on television Friday afternoon and made some of the most remarkable (and remarkably scary) comments about federal courts that I think we’ve ever heard from a senior White House official. Reacting to a series of high-profile losses in immigration cases this week, Miller raised the specter of President Trump suspending habeas corpus:

Well, the Constitution is clear. And that, of course, is the supreme law of the land, that the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus can be suspended in a time of invasion. So … that's an option we're actively looking at. Look, a lot of it depends on whether the courts do the right thing or not. At the end of the day, Congress passed a body of law known as the Immigration Nationality Act which stripped Article III courts, that’s the judicial branch, of jurisdiction over immigration cases. So Congress actually passed what’s called jurisdiction stripping legislation. It passed a number of laws that say that the Article III courts aren't even allowed to be involved in immigration cases.

I know there’s a lot going on, and that Miller says lots of incendiary (and blatantly false) stuff. But this strikes me as raising the temperature to a whole new level—and thus meriting a brief explanation of all of the ways in which this statement is both (1) wrong; and (2) profoundly dangerous. Specifically, it seems worth making five basic points:

First, the Suspension Clause of the Constitution, which is in Article I, Section 9, Clause 2 is meant to limit the circumstances in which habeas can be foreclosed (Article I, Section 9 includes limits on Congress’s powers)—thereby ensuring that judicial review of detentions are otherwise available. (Note that it’s in the original Constitution—adopted before even the Bill of Rights.) I spent a good chunk of the first half of my career writing about habeas and its history, but the short version is that the Founders were hell-bent on limiting, to the most egregious emergencies, the circumstances in which courts could be cut out of the loop. To casually suggest that habeas might be suspended because courts have ruled against the executive branch in a handful of immigration cases is to turn the Suspension Clause entirely on its head.

Second, Miller is being slippery about the actual text of the Constitution (notwithstanding his claim that it is “clear”). The Suspension Clause does not say habeas can be suspended during any invasion; it says “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” This last part, with my emphasis, is not just window-dressing; again, the whole point is that the default is for judicial review except when there is a specific national security emergency in which judicial review could itself exacerbate the emergency. The emergency itself isn’t enough. Releasing someone like Rümeysa Öztürk from immigration detention poses no threat to public safety—all the more so when the release is predicated on a judicial determination that Öztürk … poses no threat to public safety.

Third, even if the textual triggers for suspending habeas corpus were satisfied, Miller also doesn’t deign to mention that the near-universal consensus is that only Congress can suspend habeas corpus—and that unilateral suspensions by the President are per se unconstitutional. I’ve written before about the Merryman case at the outset of the Civil War, which provides perhaps the strongest possible counterexample: that the President might be able to claim a unilateral suspension power if Congress is out of session (as it was from the outset of the Civil War in 1861 until July 4). Whatever the merits of that argument, it clearly has no applicability at this moment.

Fourth, Miller is wrong, as a matter of fact, about the relationship between Article III courts (our usual federal courts) and immigration cases. It’s true that the Immigration and Nationality Act (especially as amended in 1996 and 2005) includes a series of “jurisdiction-stripping” provisions. But most of those provisions simply channel judicial review in immigration cases into immigration courts (which are part of the executive branch) in the first instance, with appeals to Article III courts. And as the district courts (and Second Circuit) have explained in cases like Khalil and Öztürk, even those provisions don’t categorically preclude any review by Article III courts prior to those appeals.

Toward the end of the video, Miller tries to make a specific point about whether revocations of “TPS” (temporary protected status) are subject to judicial review. Here, he appears to be talking about a California district court ruling in the TPS Alliance case, in which the Trump administration is currently asking the Supreme Court for a stay of the district court’s injunction (the appropriate remedy in case the district court erred). And as the plaintiffs’ response brief in the Supreme Court explains in detail, the district court had very good reasons for holding that it had the power to hear their case.

I don’t mean to overstate things; some of the questions raised by the INA’s (notoriously unclear) jurisdiction-stripping provisions can get very messy. But there’s a big difference, in my view, between reasonable disagreements over the language of complex jurisdictional statutes and Miller’s insinuation that Congress has categorically precluded judicial review in these cases. It just hasn’t.

Fifth, and finally, Miller gives away the game when he says “a lot of it depends on whether the courts do the right thing or not.” It’s not just the mafia-esque threat implicit in this statement (“I’ll make him an offer he can’t refuse”); it’s that he’s telling on himself: He’s suggesting that the administration would (unlawfully) suspend habeas corpus if (but apparently only if) it disagrees with how courts rule in these cases. In other words, it’s not the judicial review itself that’s imperiling national security; it’s the possibility that the government might lose. That’s not, and has never been, a viable argument for suspending habeas corpus. Were it otherwise, there’d be no point to having the writ in the first place—let alone to enshrining it in the Constitution.

If the goal is just to try to bully and intimidate federal judges into acquiescing in more unlawful activity by the Trump administration, that’s shameful enough. But suggesting that the President can unilaterally cut courts out of the loop solely because they’re disagreeing with him is suggesting that judicial review—indeed, that the Constitution itself—is just a convenience. Something tells me that even federal judges and justices who might otherwise be sympathetic to the government’s arguments on the merits in some of these cases will be troubled by the implication that their authority depends entirely upon the President’s beneficence.

***

It’s certainly possible that this doesn’t go anywhere. Indeed, I hope that turns out to be true. But Miller’s comments strike me as a rather serious ratcheting up of the anti-court rhetoric coming out of this administration—and an ill-conceived one at that.

We’ll be back (no later than) Monday with the next regular issue of “One First.” If you’re not already a subscriber, I hope you’ll consider signing up—and upgrading to a paid subscription if your circumstances permit.

I hope you all have a great weekend—well, except Mr. Miller.