An old tweet from Vivek Ramaswamy, now co-head of the Department of Government Efficacy:

I was surprised to see someone with such experience in the pharmaceutical industry say this, because it goes against how I understood the FDA to work.

My model goes:

FDA procedures require certain bureaucratic tasks to be completed before approving drugs. Let’s abstract this into “processing 1,000 forms”.

Suppose they have 100 bureaucrats, and each bureaucrat can process 10 forms per year.

Seems like they can approve 1 drug per year.

If you fire half the bureaucrats, now they can only approve one drug every 2 years.

That’s worse!

A few years ago, I debated Kevin Drum about (what I considered) a particularly egregious case where the FDA dragged its feet approving a life-saving medication. Drum argued that the FDA had behaved well. In support, he found some quotes from the doctor working on the medication, who praised all the FDA bureaucrats she had interacted with, calling them extremely helpful. This bothered me for a while, until I realized that of course it was true. In the model above, each bureaucrat processes ten forms. If the bureaucrats are benevolent, this might look like talking to the doctors, walking them through the process of figuring out their ten forms, and doing the work to add their ten forms to the FDA’s growing pile of evidence supporting the application.

All of this co-exists comfortably with the insight that making doctors fill out a thousand forms before they can use a medication is an impediment to medical progress.

This really sunk in for me when I read an article about the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban in 2021. Many Afghans had collaborated with the Americans, eg as translators, in exchange for a promise of US citizenship. As the Taliban advanced, they called in the promise, begging to be allowed to flee to America before they got punished as traitors. The article focused on a heroic effort by certain immigration bureaucrats, who worked around the clock with minimal sleep for the last few weeks before Kabul fell, trying to get the citizenship forms filled in and approved for as many translators as possible. It made an impression on me because nobody was opposed to the translators getting citizenship, and the bureaucrats were themselves the people in charge of approving citizenship applications, so what exactly was forcing them to go to such desperate lengths? If you ponder this question long enough, you become enlightened about the nature of the administrative state.

If you don’t, you end up like Ramaswamy, who seems to think that halving the number of bureaucrats will halve the number of forms that need to be filled out. I think in his worldview, the FDA will think “Now that we have fewer bureaucrats, it would take forever to complete our current process, so let’s simplify the process.”

Maybe he is working off a thesis where red tape expands to consume the resources available to it (as measured in bureaucrats). But my impression is that the amount of red tape is determined more by things like:

— How likely is it that their decision will get challenged in court?

And if it gets challenged in court, what amount of paperwork do they have to show the judge to prove that they made the decision on a “reasonable basis”?

For example, when I type “FDA sued” into Google, the top result is a news story from a few days ago, saying that an environmental organization sued the FDA for not listening to their earlier request to ban phthalates from food.

Six years ago, the environmental groups submitted a petition (the catchily-named “Food Additive Petition 6B4815”) demanding that the FDA ban 28 phthalates. Two years ago, after consulting with industry, the FDA finally banned 23 phthalates but said that the other five were okay, releasing a 58 page decision explaining its decision. Two days ago, the environmental groups sued, saying the remaining 5 phthalates are still bad.

I assume the lawsuit will nitpick the details of the the 58 page decision, trying to prove that it it didn’t violate any of hundreds of federal laws saying that bureaucratic decisions must be reasonable, bureaucratic decisions must be based on science, bureaucratic decisions must respond to the petitioners’ complaints, bureaucratic decisions cannot have disparate impacts on different races, etc. I also assume that if the FDA had banned all the phthalates, they would have faced an equally serious lawsuit from Big Phthalate saying they were unfairly crippling business.

Why does it take six years to respond to a petition? My guess is because they knew they would get sued and so they have some sort of million-step process that addresses every single thing you can sue over, so that they can prove to the court that their process addresses all possible complaints and they followed it to the letter.

If you cut their bureaucrats in half, that doesn’t mean there will be fewer steps in the process. It means they’ll keep wanting not to get sued, the process will stay the same, and everything will take twice as long.

— What has Congress mandated that they do?

For example, when I Google “Congressional FDA mandate”, I get a page on HR 7248, a bill currently making its way through Congress, which says:

This bill requires the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to establish a process that supports nonclinical testing methods for drug development that do not involve the use of animals.

Specifically, the FDA must establish a pathway by which entities may apply to have nonclinical testing methods approved for use in a particular context. Qualifying methods must be intended to replace or reduce animal testing and to either improve the safety and efficacy of nonclinical testing or reduce the time to develop a drug. The FDA must issue its decision within 180 days of receiving an application. The FDA must also prioritize the review of applications for drugs that are developed using an approved nonclinical testing method.

The FDA must annually post a report on its website that summarizes the results of the bill's implementation, including the number of applications received, types of methods that were approved, and the estimated number of animals saved as result of these methods.

So the FDA has to establish this process and post an annual report on its website. How many bureaucrats per year does this take? Maybe five? If you halve the number of people at the FDA, you still need a constant five bureaucrats to comply with this particular law.

If the bill passes, the FDA comes up with a nonclinical testing process, and someone (eg the nonclinical testing industry) doesn’t think it’s good enough, they can sue the FDA for not following the law. How good a nonclinical testing process will the FDA need in order to avoid lawsuits under this bill? I assume there is a large body of administrative law answering that question, and that it will take many bureaucrats to figure this out.

Finally, I admit I’m a bit confused by this. IIRC “nonclinical testing” refers to things like testing drugs on stem cells or artificial organs instead of humans. You can obviously do this for some parts of the drug testing process, but not others; the FDA has already adjusted for this and integrated it into their guidelines to some extent. I can’t tell whether this law is a righteous attempt to correct bureaucratic foot-dragging, or a powergrab by Big Nonclinical Testing demanding that the FDA privilege their products over other forms of experiment. If the latter, the FDA may try to come up with some fake pathway that satisfies the letter of the law without really giving Big Nonclinical Testing any unfair privileges, and Big Nonclinical Testing will probably sue and say it violates this bill. How many bureaucrats do you think it will take to manage that?

— How much will they get yelled at if they take too long to approve drugs, vs. if they mistakenly approve a bad drug?

This is the basic determinant of all FDA drug approvals.

Halving the number of FDA bureaucrats wouldn’t have literally zero effect on this balance. It would mean that approving new drugs would be delayed twice as long. This would be a little more outrageous than the current delay, and might shift an outrage-minimizing FDA director slightly in the direction of cutting rules. But solve for the equilibrium: there would still be more delay than there is now. Also, I don’t think public outrage about long drug delays is linear with regard to delay, and public outrage at bad drugs is constant and large. So I think at best, firing bureaucrats would shift this balance a small amount, and only by making everything overall worse.

II.

One possible objection: this assumes that the average bureaucracy is like the FDA drug approval process. But the FDA drug approval process’ job is to approve things. Maybe the average bureaucracy’s job is to ban things. Then decreasing their capacity would be good.

(Vivek gets to be main example here because he tweeted, but the same considerations apply to Elon: even though the government as a whole is delaying SpaceX rocket launches, individual bureaucrats might be speeding them up through the same 1000-forms logic as in the FDA case)

There’s certainly a spectrum from the most approval-focused bureaucracies to the most ban-focused bureaucracies. Thinking hard about this spectrum would be a step up from “instantly” firing 50% of all bureaucrats based on social security number. So maybe a steelman of Vivek’s point would be to fire 50% of people in the ban-focused bureaucracies (and maybe double the number of people in the approval-focused ones?)

I’m still skeptical that this is how it works. The past few years have seen the cryptocurrency industry demand regulation, and the government mostly fail to step up (though crypto businesses hope the Trump administration will do better). Why do crypto businesses want to be regulated more? Because the alternative is something where it’s not clear what’s legal and anyone could be sued or shut down at any time. The chief legal officer of Coinbase, from the second link:

All of us are begging for sensible standards that would allow us to get back to building great products and services and spend less time and frankly, less money, arguing over legal definitions and statutes.

This isn’t because anyone specifically banned crypto. It’s because there are bans on other things (like unlicensed securities, money laundering, etc) that crypto is vaguely related to, sometimes an agency regulating these things will tell a crypto company “sorry, we think you’re illegal”, and crypto wants some specific list of things it can follow that explicitly establish it as on the right side of money-laundering and security-licensing laws. Obviously industries would prefer that these be simple and easy standards (“oh, don’t worry, you don’t have to worry about money laundering if you’re a crypto company”), but they would settle for strict regulations as long as the regulations carve out some ability for them exist at all.

I’ve seen the same thing play out in another area I follow, cultured meat. There are many laws about what meat you can and cannot sell, how the animals have to be treated, what the sanitation standards are, et cetera. Some of these standards make no sense when applied to cultured meat; others, cultured meat naturally fails by default (you can’t prove you’re treating the animals in a certain way because there are no animals). Others are novel philosophical questions (can you sell cultured meat without saying it’s cultured? How big does the print need to be before it counts as saying that it’s cultured? What about on restaurant menus?)

Situations like these mean that there’s no clear distinction between default-yes and default-no bureaucracies. There’s no explicit ban on crypto or cultured meat. But if you cripple bureaucracies’ ability to interact with these fields, it doesn’t mean they’re fully legal, free, and happy forever. It means they’re stuck in regulatory limbo.

III.

So it seems like you don’t want to fire bureaucrats, you want to cut red tape. In our toy model, you want to reduce the number of forms from 1,000 to (let’s say) 100. Then the same number of bureaucrats can get drugs approved ten times faster.

In our non-toy actual model of what’s going on, this would require changing incentives.

Maybe you could change judicial procedures so that fewer people sue, or the FDA needs less evidence to win any given lawsuit. This sounds hard (Vivek and Elon seem more qualified to wield chainsaws than to understand legal minutiae), possibly illegal (does the administrative branch even control how judicial procedure works?), and politically unpopular (this basically looks like telling people “f@#k you, companies can put as many phthalates as they want in food, we don’t have to prove that this decision is evidence based, and you’re not allowed to challenge us.”)

Or it would require Congress to repeal legislation mandating things. These Congressional mandates are probably things that Congressmen and their constituents (either real constituents or special interests) care a lot about, so good luck getting them repealed. Also, doesn’t Congress pass like one bill per year now?

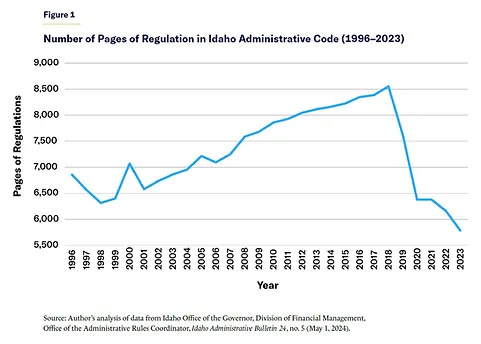

This would normally make me pessimistic, but Vivek and other anti-bureaucracy activists have pointed to a recent success story: Idaho.

Idaho cut their regulatory code by 38% in 2019, and since then it’s only gone down. How did they decrease red tape so fast? They did it through the power of nominative determinism. In that year, they elected a governor named Brad Little. His administration is called the Little Administration. Obviously government had to get smaller.

But on a purely exoteric level, what methods did they use to pull this off?

This CPAC article gives the basic story:

The Little administration instituted sunset provisions that review each regulation every five years and make sure it’s justifiable.

The Idaho regulatory code is short enough that individual agencies’ portions are only a few hundred pages, and humans from those agencies can read the few hundred pages and see if they make sense.

Upon being read, many of the regulations were not justifiable, for example “rules for a lottery game show that never aired”.

The Idaho legislature is competent and reviews all regulations proposed by the state’s regulatory agencies (though it looks like they only strike down 5%).

Regulatory agencies have to justify every new regulation they make, and (unless they can present a compelling case why not) repeal two old regulations per one new one.

I don’t have a good sense for how well this could work at the federal level. The pessimistic case is that the governor wanted a legacy of repealing regulations, there are many completely useless regulations in the code (like the one for the lottery show that never aired), bureaucrats removed these from the code to satisfy the governor, but these don’t have a big effect in real life (the show never aired, so it’s not like anyone was affected by the regulations!) This kind of thing would lower the number of pages in the regulatory code (which isn’t nothing!) but not make ordinary people’s lives easier.

But the article suggests that ordinary people’s lives were made easier, and that the move has brought businesses to Idaho. It gives the example of repealing a regulation about what kind of doors pharmacies can have. Here I guess the theory of change is that there are many stupid regulations that nobody wants to defend, and if you force people to read them and put a trivial amount of effort into justifying them, they’ll fold immediately.

Are the most burdensome federal regulations more like the pharmacy door, where nobody can remember why they exist? Or are they more like phthalates, where environmental groups and industry groups fought each other to a bloody standstill, and any attempt to change anything will be met with lawsuits?

More important, can DOGE get nominative determinism on their side? “Ramaswamy” means “Lord Rama”, who - although cool - is not really associated with smallness. But it seems like the word “Musk” may ultimately derive from the Indo-European word múh₂s, meaning “mouse”. This makes me bullish on DOGE’s eventual success.