| archive - contact - sexy exciting merchandise - search - about |

| ← previous | December 1st, 2025 | next |

December 1st, 2025: December! It's a new month, filled with new experience too, but also, FAMILIAR experiences (like comics that are new but use the same pictures but also have been using the same pictures for a few decades at this point)!!! – Ryan | ||

SUMMARY

A four-year study has revealed brown rats actively preying on bats at two urban hibernacula in Northern Germany. At Segeberger Kalkberg cave—home to over 30,000 bats, mostly Daubenton’s and Natterer’s—infrared cameras in 2020 captured rats jumping to intercept bats in flight or attacking landed ones.

In just five weeks, 30 predation attempts and 13 kills were recorded. A rat cache contained 52 bat carcasses. From 2021 to 2024, thermal imaging at Lüneburger Kalkberg documented rat activity near crevices and uncovered another identical carcass pile, confirming the behavior at both sites.

The extended timeline allowed researchers to gather video, thermal data, mist-net species confirmation, and carcass evidence across seasons, ensuring solid conclusions before the 2025 submission.

Rats hunt in complete darkness using whiskers to sense wingbeat air currents, then grab prey with forepaws. A colony of 15–60 rats could kill 2,100–8,400 bats per winter—up to 7% of Segeberg’s population.

Both bats and rats are major reservoirs for coronaviruses and paramyxoviruses. This direct predation creates a new interface for bat coronaviruses to spill over into rats, potentially amplifying and spreading them to humans and livestock. No immediate outbreak risk exists, but the pathway raises One Health concerns.

Do me a favor and try the following. Hold one hand about a foot away from your nose, palm facing the floor. With your other hand, or with the help of a trusted third party, pinch the skin on the back of your hand between two fingers, like this:

Watch closely, and release. What happens?

In my abnormally medically-trained household, this test is commonplace, and I expect that at least some portion of my audience is familiar with it. However, for the uninitiated, the skin turgor test is a quick method of determining just how dehydrated you really are. The more slowly your pinchy bit returns to normal, the worse it is.1

I love the skin turgor test because it offers a direct window into a person’s state of peripheral hydration, i.e. how much water is actually making it into peripheral tissues like the skin, regardless of how much the person is drinking. In comparison, the classic “pee color” test is just a proxy indicator. Light-colored urine tells you that there’s a lot of flow through your kidneys (hence a lower concentration of waste products in the output), but that doesn’t necessarily tell you that any of the fluid you’re ingesting is being absorbed into the peripheral tissues. It’s really, really easy to get a false negative on dehydration if you’re only looking at your pee.

So, let’s talk about the Space of Nameless Misery. Part of the Misery of the Space of Nameless Misery is that it’s Nameless. You’re not upset about any one thing in particular; you’re not having a reasonable reaction to some life circumstance; you’re just feeling like shit for no apparent reason, and everything is horrible, and despite the fact that you know academically that this is a transient state just like every other you do not feel that way because you feel like a cold dog turd lying halfway on the sidewalk in front of a run-down Burger King. And it’s raining.

Yes, the Space of Nameless Misery is indeed Miserable. The skin turgor test might be your way out.

Look, I’m not saying that pinching the back of your hand will reveal the glory and brilliance of a world renewed. I’m not saying anything like that. But what it will do is give you information, along with a potential course of action.

If your skin is tenting at all—if it doesn’t immediately snap back into place—you now have a mission: hydrate yourself. If plain water feels bad, which it might for a variety of reasons, consider carbonated water, broth, or a sports drink or electrolyte solution.2 Whatever garbage you’re feeling? Go ahead and feel it, but feel it while drinking something. Your body needs the fluids regardless of whether or not dehydration is to blame.

In my experience, much of the Space of Nameless Misery is just dehydration. By forcibly encoding the “Feeling shitty? Try a pinch” pathway, I’ve been able to gather immense amounts of data correlating internal emotional states with levels of hydration, and what I’ve found is that the cold-sidewalk-turd flavor of feeling in particular is, without fail, a symptom that resolves with n-many glasses of water for some n ≥ 1.3

Sometimes, though, you feel like shit for no apparent reason and your skin is as springy as the day you were born. This is still useful information. Data is data is data, and every bit of data you gather refines your understanding of your own experiential patterns. Experience need not be relegated to the mystical realm; we can science that shit just like anything else.

Perhaps even more importantly, you’ve now taken a step towards trying to understand the feeling, i.e. you’ve become curious about it. As with all creatures that live in the realm of emotion, becoming curious loosens the thing’s grip on you ever so slightly. And it’s simple to do. All it takes is a pinch.

There are several other specific miseries that arise from concrete physiological needs. I can only speak for myself here, but I’ve heard from strangers on the internet that their concrete-cause miseries present similarly. Some of these are:

Everyone hates me, including my loving family and the squirrels in the park, and everything is overwhelming: You need sleep.

I need to make a decision but my brain is slippery: You need food.

I want my essence to be spread like cream cheese: You need to engage your muscles.

After learning about the skin turgor test, people often end up trying it really frequently. The problem here is that the more you pinch your skin, the more blood you bring to that area, which necessarily means more fluid in the tissues. Try repeating the test three times in quick succession right now. You’ll likely notice that the tenting time lessens at each iteration, even if only slightly.

Similarly, you can alter your results by engaging in “extreme activity” that either brings a lot of blood into the hand or drains a lot of blood from the hand. To test this yourself try lying sideways on a bed or couch, with one arm pointing down off the side and your other one pointing straight up. After some amount of time in this position, return to sitting and have a friend perform the test on each of your hands. You can also test this by warming one hand and cooling the other if you don’t feel like adopting strange positions.

If “in the field” you end up performing the test under altered conditions, it’s not the end of the world. However, make sure to switch hands if for whatever reason you need to perform the test more than once in quick succession.

Weird Al is famous for writing “song parodies.” But most of his “parody” songs are not really parodies as understood in US copyright doctrine.

Parody is not just “rewriting the lyrics.” I can’t take a Toni Basil song about a man named “Mickey,” rewrite the lyrics to be about a woman named “Vicky,” and then claim that it’s “my song” and defend my use of Toni Basil’s melody by calling it a parody.

Parody is protected by “fair use” copyright doctrine when it’s used for the purpose of commenting on the original. Or, to quote the decision of Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994), a parody is a work that “at least in part, comments on that author’s works.”

For example, one Weird Al song that does qualify as fair-use protected “parody” in this sense “Smells Like Nirvana.” Weird Al is lifting the melody of Nirvana’s song “Smells like Teen Spirit,” but the fact that he’s using a Nirvana melody and mimicking Kurt Cobain’s singing style is part of the commentary: it wouldn’t make sense if he took a Queen song and rewrote the lyrics to make fun of Nirvana.

But most of the songs we colloquially call “Weird Al parodies” wouldn’t qualify as parody under the Campbell standard if he tried to rely on fair use alone. They don’t really “comment on” the original; they just use the melody as a vehicle for a completely different joke, as Weird Al does when he rewrites “Mickey” to be about the I Love Lucy character “Ricky.” Absent permission, they’d be on very shaky legal ground.

Charles J. Sanders and Steven R. Gordon, writing in Fordham Intellectual Property Media & Entertainment Law Journal in 19901, put it like this (PDF link):

Application of the “verbatim copying” threshold test would present an insurmountable hurdle to any claim of fair use by Mr. Yankovic. His taking of the full chord structure, melody, and portions of the lyrics of the original underlying musical compositions which he parodies is clearly substantial enough to pre-empt a finding of fair use as a matter of law, regardless of any number of “mitigating” circumstances which might exist.

It’s pretty well-known that Weird Al seeks permission from the artists he “parodies.” What’s less-known is that Weird Al actually pays royalties to the artists of the original song. Again, per Sanders and Gordon (emphasis added):

Having concluded that his song and video parodies are not legally characterizable as fair uses, Mr. Yankovic licenses all of the musical compositions and music videos he parodies directly from their respective copyright owners. According to his attorney, Chuck Hurewitz of the Beverly Hills law firm of Cooper, Epstein and Hurewitz, Weird Al generally gets a writing credit and a copyright interest in the song parody, which he shares (in varying royalty ratios) with the writers of the original underlying work.

…Mr. Hurewitz asserts that Weird Al’s substantial market success is responsible for the willingness of copyright owners to grant him permission to parody their musical compositions, and has made it possible for Yankovic to bargain for a lucrative share in the copyright of the parody version of the song.

Weird Al often tells stories about how he talked directly to specific musical artists to get their permission for a song, which often include charming anecdotes about how he met them in person or over the phone to get a “yeah, that sounds fun.” But that is not the end of the conversation, it is the start of a negotiation between “my people and your people.”2

This came up more recently in a 2017 interview with Vulture:

Vulture: I didn’t even realize that once you start parodying that the original songwriters get any money.

Weird Al: Yeah, we negotiate a deal for every single parody. Generally, the original songwriters will keep the publishing and we’ll split the writer’s royalties. They wind up making more money than I do, but that’s fair, I think.

But not all of his “parodies” are directly using other people’s music. Sometimes, he’s just using their style. (For example, “Bob” is not a parody of one specific Bob Dylan song; it’s a pastiche.) In one Q&A, a fan asked, “do you have to ask permission to do style parodies?” Al answered:

Well, as I always say, we live in a country where anybody can sue anybody else for any reason at any time, so it’s always a gray area. However, even though I always get permission for the parodies, I don’t feel obligated to do the same for “sound-alikes.”

For years, I had bought into this false narrative that “Weird Al always asks for permission, even though he doesn’t have to, just because he’s such a swell guy.” And this isn’t really true.

For the bulk of his catalog, Weird Al can’t comfortably rely on fair use; his songs are not “parodies” in the Campbell sense. In practice, if he didn’t ask permission and share royalties, he’d be inviting expensive lawsuits he might well lose, so the “permission” isn’t just a chivalrous gesture, it’s the legal bedrock of his entire business model.

I was wrong to give Weird Al credit for asking “even when he doesn’t have to,” because in a counterfactual world where he didn’t need legal permission, he wouldn’t ask for it. We know this because he told us in the aforementioned fan Q&A when he was asked about “style parodies,” which mimic an artist’s style without directly lifting their melody verbatim.

So, the answer to “how does Weird Al get away with it” is that he doesn’t “get away with it.” He pays people for the right to use their music, except in the case of style parodies, where he doesn’t need to.

But that does leave the open question of how all the other song parodies get away with it. For example, if you go onto YouTube, you will see lots of song parodies from smaller artists who seem to not be getting sued. Is what they’re doing legally protected?

No, not really. Much of it is technically copyright infringement, in much the same way that fan fiction and fan art is technically copyright infringement. And, much like fan fiction and fan art, the rights holders generally don’t sue you over it if you aren’t selling it.

It’s hard to prove “damages” when a 19-year-old makes a song parody that gets 100,000 views on YouTube, so there’s not much point in legal action and the accompanying financial and PR cost of suing a fan over a silly song.

Weird Al is not a teenager. He is making millions of dollars from his musical performances, he is selling CDs with other people’s melodies on him.

But, while Weird Al is currently a multi-millionaire making a bunch of money from his music, it is also descriptively true that he was once a broke teenager who recorded “Another One Rides the Bus” in the bathroom at his college radio station, and he probably didn’t have Queen’s permission at the time he produced that accordion recording. And that’s fine when you’re a college student making funny tapes.

Eventually, Weird Al “leveled up” and started making actual money from his music. At that point, he became the sort of person who could be a very attractive target for lawsuits if he kept doing unlicensed parodies, and so he developed the practice of asking for permission. Given how much of his catalog doesn’t fit the Campbell parody template, he’d be taking serious legal risk if he didn’t license everything. This evolution seems like a practical (and legally advisable) move.

Weird: The Al Yankovic Story is a comedy film about the (fictional) life of Weird!Al, co-written by Weird Al. As you’d expect from the man who made his career through the form of song parodies, the film parodies the form of the musical biopic.

One critical plot point in Weird!Al’s fictional life is that after becoming famous for song parodies in the early 80’s, he decided to pivot to writing original songs, starting with “Eat It.” They’re very clear about this point to make sure the audience doesn’t miss the premise of this joke:

(Weird!Al plays the tape for Eat It)

Ben Scotti: I’m sorry, I don’t recognize the tune. What’s the song you’re parodying here?

Weird Al: I’m not parodying anything. This song is completely original.

Ben: Wait, you wrote the words…and the music?

Al: That’s right.

Ben: Just to be perfectly clear, you’re saying this is not a parody of an existing song, but a completely original composition which you wrote all by yourself?

Al: Yup.

Ben: Not based on anyone else’s song in any way?

Al: Did I stutter?

And of course they complete the inversion of real life later in the film:

Toni Scotti: I thought you should hear it from me first. Michael Jackson has just released a new single called “Beat It.” It’s…well, it’s a parody of “Eat It.”

Weird Al: What? You mean the kid from the Jackson Five? Why is that has-been trying to ride my coattails?

Tony: Uh, he’s actually got a pretty successful solo career now—

Weird Al: You’re telling me Michael Jackson recorded a parody of MY SONG?

Tony: Yeah, that’s what I’m saying. Same music, different words.

Weird Al: What kind of sick freak changes the words to someone else’s song? “Beat It,” huh. It’s about eggs?

Tony: It’s not even about food!

In this beat of a movie he wrote, Weird Al is taking credit for another musician’s work. In a vacuum, that seems like it would be a bad thing to do. But the audience very clearly knows what he is doing, and the joke only works because it’s clear what he’s doing. Thriller-Bad-Dangerous-era Michael Jackson is the single most-recognizable pop musician in history. That’s what makes the joke work.

So when Weird!Al says “I’m not parodying anything. This song is completely original,” we understand that Weird Al is not trying to take credit for another musician’s work.

This is what much of Weird Al’s career is premised on: he takes other people’s work, he riffs on it, but nobody would mistake his songs for the original.

This Weird Al style of using other people’s work but not stealing it works because he generally conducts himself in a way that is beyond reproach:

Weird Al is often picking artists who his audience is already familiar with: he made his early career by parodying Queen, Madonna, Michael Jackson. And even on the occasions when Al parodies a smaller artist,

Weird Al always credits his sources. When you open the CD case to look at the lyrics, it’s right there at the top of the sheet: he gives you the song he parodied, the artist he parodied, and even the featured artist of the parodied track. So even if he were to parody a smaller artist, the audience would know, “someone else wrote this melody.” The smaller artist might even benefit from the attention.

Weird Al asks permission and pays the artist when he does his parody!

Weird Al is engaging in transformative content: he is taking songs in non-comedy genre, and changing them by putting a comedy spin on them. Artistically, he is adding something new that wasn’t there.

From this, we can imagine a photo-negative version of this man, an imaginary character who I will call “Evil Al” to distinguish him from Weird Al.

Evil Al would do the following:

Evil Al would, at the height of his career, pick a smaller artist to parody (one who had yet to go gold), making it more likely that his fans would hear his version first and never realize that it was an imitation. And then:

Evil Al would not credit the original artist or the original song that inspired his own song. He would never, ever acknowledge or mention the name of the original song.

Evil Al would not pay them royalties, making use of the “style parody” loophole, even though his song was clearly based on one specific song.

That would be legal, but in my opinion, it would be bad. (As D&D teaches us, “lawful/chaotic” and “good/evil” are orthogonal axes.)

Evil Al might then go on to move even further in the direction of denying the original artist credit for their work:

As we already established, Evil Al isn’t giving credit to the original artist of this one specific song. But he might selectively give credit to the artists of the more popular songs, so that when listeners see that 8 of the 11 songs on the album are listed as parodies, they might incorrectly assume that the other 3 are originals.

Evil Al would then perform this song for decades, and talk about it in public for decades, without directly mentioning that it was based on another artist’s song

To give himself some plausible deniability, Evil Al might generally acknowledge that the artist of the original song had inspired him, but he wouldn’t give them credit for some other song, and he’d only mention them in a longer “list of artists who inspired me” to make it harder for his fans to draw the connection

Evil Al would not make his version of the song transformative. Instead, he would start with a song that was already an absurd comedy song, then make his version (also an absurd comedy song.)

And then, 25 years later, Evil Al would continue to perform this song as his closer at concerts, in front of thousands of fans, most of whom still believed that this incredibly famous song was 100% an original and not a parody based on another song. This incredibly famous Evil Al song would of course have its own Wikipedia page, but that Wikipedia page would make no mention of the original song that was very clearly the inspiration for this parody (which his fans don’t recognize as being a parody).

I regret to inform you that the “imaginary character” of Evil Al, as I have described him, is a real person. His name is Alfred Yankovic.

If there is one thing that I would like Weird Al fans to take away from this post, it is that Albuquerque is not an original song.

This is new information to every Weird Al fan I encounter, and I’ve encountered a lot of Weird Al fans. This is a weird misconception to have about a particularly famous Weird Al song, especially when Weird Al is not an artist typically known for producing original songs: you’d think the prior would be “this is probably a parody song,” and yet everyone seems to think it’s a Weird Al original.

I think this case is best made simply by exposing you to the music. Here is Albuquerque by Weird Al, and here is Dick’s Automotive by the Rugburns.

I think that the content of the song speaks for itself: it’s not literally the same melody, but the similarity is unmistakable. For those who don’t want to listen to an 8-minute song, here are just a few of the points of similarity:

Both songs are very long. (The original is 8:41, Weird Al’s version is 11:23)

Both are mostly spoken-word narration, a made-up story of a person who moves away from home and has truly bizarre things happen to them

The chorus consists of repeating the name of the song over and over again (either “Dick’s Automotive” or “Albuquerque”)

Both songs start with a sprawling cumulative sentence that begins keeps on piling on prepositional and apositive phrases to overspecify the setting

At one part in the narrative, there is a horrifying description of abrupt violence involving a chainsaw

The story includes a part where someone is knocking at the door, and the “door knock” is recreated with the sound of a snare drum with an almost identical cadence (despite this not being the standard “door-knocking” cadence in real life)

The Steve Poltz enunciation of “flat shooby doo wop down” is reproduced by Weird Al in his own lyric, “wakka wakka doo doo yeah.”

There’s a bit in the song with a back-and-forth exchange where the answer is repeatedly “no,” followed by a character changing the formula with a sequitur which gets an affirmative response. (In Dick’s Automotive, this takes the form of a job interview. In Albuquerque, it’s an exchange at a donut shop)

I could go on, but I really think the content and sonic qualities of the two songs speak for themselves. Albuquerque by Weird Al is clearly a “style parody” of Dick’s Automotive. Steve Poltz, who wrote Dick’s Automotive, says basically the same thing. And yet for 25 years, I was unaware of this song’s existence, despite being a huge fan of Weird Al and “Albuquerque.”

I am not bothered by the existence of Albuquerque. I think the song is fun and funny, even if The Rugburns did it first. But the majority of Weird Al fans persist in the mistaken belief that Albuquerque is an original song.

Part of this comes from the fact that, at the time Weird Al released the album in 1999, he did not credit “style parodies.” So fans see that 8 of the tracks on the CD are described as “parody of…” while Albuquerque does not have this label, and they incorrectly assume that means it’s an original song.

And Weird Al, for his part, seems to have actively declined the opportunity to disabuse his fans of the mistaken notion that Albuquerque is based on Dick’s Automotive. In 2011, more than a decade after the song’s release, he had an interview with The AV Club where he had a lot to say about the song, but never got around to mentioning Dick’s Automotive provided most of the inspiration for the form of “having a ridiculous spoken word story that goes on for 8+ minutes, full of absurd events like chainsaw violence.” The closest he gets to giving credit is this:

This song is meant to be sort of in the style of The Rugburns and Mojo Nixon and George Thorogood and any other kind of hard-driving rock narrative. And you know, I made it a little more ridiculous than the normal kind of rock narrative, but nonetheless, it’s in that vein.

(I’d dispute Weird Al’s premise that his version is “more ridiculous.” Dick’s Automotive was already ridiculous and transgressive; Weird Al just doing an “absurd comedy version” of what was already an absurd comedy song.)

This thing where The Rugburns get acknowledged by Al only in the broad sense of being part of a longer list is also true of the FAQ on his website, where he does get a bit closer to acknowledging that The Rugburns were responsible for inspiring Albuquerque in a way that Mojo Nixon and George Thorogood were not:

The artists that I’ve style-parodied range from the extremely popular (Bob Dylan, Nine Inch Nails, James Taylor, etc.) to the semi-obscure (Tonio K, The Rugburns, Hilly Michaels, etc.)

I think that Weird Al has painted within the boundaries of what’s legal, and while I wish he’d given more credit to The Rugburns, he does not “owe” it to them to name a specific song as a creative inspiration (as opposed to saying something to the effective of ‘I owe creative inspiration to many sources, including…’) And in the grand ranking of “unethical behavior by famous musicians,” this ranks very low on the list.

So why am I making a big deal out of it?

Partly, because Al himself realizes that he did The Rugburns a disservice, even in the FAQ of his website where he talks broadly about the artists who he has “style parodied,” with The Rugburns being just one entry among that list:

…they’re all favorites of mine, and my homages to them are always done with great affection and attention to detail. In the past, I never put the artists that I style-parodied in the Special Thanks section on my album, mostly because I wanted to see if fans could figure out what I was doing (without being given any obvious hints). But I’ve come to realize that’s a little unfair to those artists – to whom I certainly owe a huge debt of gratitude – so I plan to acknowledge all my musical influences in the CD liner notes in the future.

It’s great that, starting in the 00’s, he began printing the names of artists on the CDs. But Al hasn’t really made any efforts to make this retroactive, even in ways that might be relatively easy, like an entry on his website.

Albuquerque is one of his famous and most beloved songs. It’s the closer of the album it appeared on, and it’s the closer at many of his live shows even to this day. And I really wish the specific song it’s based on would get any mention at all from Al, not only for the sake of The Rugburns and their fans, but for sake of Weird Al’s fans!

I was a huge Weird Al fan as a kid. If I had gotten to hear Dick’s Automotive when I was a teenager, I probably would have enjoyed it a lot, and I wish Al had given me that opportunity. Instead, I spent over two decades mistakenly believing it was a Weird Al original.

Part of this also comes from my general desire for the world to be more legible. I have spent hundreds of hours on the music lyric Genius adding annotations (including to Weird Al songs) because I want to make it easier for people to find information about the artists and songs that they enjoy. (And I enjoy the process of reading magazine interviews and watching concert recordings looking for all the places where my favorite musicians have talked about their work; the annotations that I leave on Genius song pages are partly an artifact that I leave for myself to keep track of what I’ve learned about each song.)

Wikipedia has high standards for sourcing, so “this is obvious to anyone who hears both songs” is not a valid source, and that seems fair enough to me. But because Weird Al has never officially acknowledged that Albuquerque is a style parody of Dick’s Automotive, despite the fact that it very clearly is one, the Wikipedia page for Albuquerque makes no mention of the source material, instead choosing to reproduce Al’s interview line about how “According to Yankovic, the song is in the style of the ‘hard-driving rock narrative’ of artists like The Rugburns, Mojo Nixon and George Thorogood.”3

I have wondered why Weird Al has never been public about the connection between Dick’s Automotive despite using Albuquerque as his concert closer for years and years and years. And I wonder if it might be for some of the legal reasons I mentioned at the top of this post.

Weird Al has done style parodies of many artists. But Albuquerque is unique among them for being a style parody of a specific song. There, it feels like he’s a lot closer to “song parody” than “genre pastiche” or “artist homage.” And that’s getting closer to the area where he’d have to pay royalties. (Remember, Weird Al pays royalties to Lorde for parodying “Royals”, but he doesn’t pay royalties to Bob Dylan for doing a genre pastiche in “Bob.”)

I don’t want to accuse Weird Al of any specific motives. But it seems descriptively true that it would be financially costly to Weird Al (and extremely inconvenient to his accountants) if Albuquerque were legally considered a song parody, rather than an artist style parody. And if he wanted to have a stronger legal case that Albuquerque was the latter, this case would be bolstered if he had a public record of saying it was inspired by a great many sources (like “the style of the ‘hard-driving rock narrative’ of artists like The Rugburns, Mojo Nixon and George Thorogood”) rather than admitting that it was substantially based on a single song by the Rugburns. I can’t know his motives, but Al’s behavior has been consistent with someone who is doing what you’d want him to do if you were his lawyer.

Maybe Weird Al is being 100% honest when he claims this song was inspired by many sources and not one specific song. Maybe you can listen to both songs, and agree with Weird Al, and disagree with me and Steve Poltz. I am curious to see what other people think, so please, if you disagree (or agree), leave a comment!

I wrote this post based entirely on my own experience, and only in the 11th hour before hitting “publish” did I do one last fact-checking search and discover that Steve Poltz, the Rugburns leading man who wrote and sang the original Dick’s Automotive, has commented on this, and I would feel remiss not to include his remarks in an interview where he talked about the the band’s live shows in the 90’s:

So Weird Al would always come out to see us. Weird Al loved a song by the Rugburns called Dick’s Automotive. Because of Dick’s Automotive, Weird Al wrote the song Albuquerque, which is one of his songs he wrote, but it’s a direct takeoff of the Rugburns, but he didn’t credit us. I kind of wish he would have, but it’s okay. He wrote Albuquerque. If you A/B Dick’s Automotive and Albuquerque, you would…[trails off]

He was always obsessed with that song, he would come in and listen to “John was living in Ocean Beach California with his girlfriend Juliet…” where I’m talking really rapid.

In the end, I am inclined to agree with Steve Poltz: Weird Al wrote Albuquerque after hearing Dick’s Automotive. Weird Al didn’t credit The Rugburns. I wish he would have. But it’s okay.

The first time I ever heard a land acknowledgment, I was on a panel at a nonprofit conference in Colorado. A Native woman stood up in the audience and started shouting and demanding the floor. Most people were confused, but a few were cheering her on. When the moderator let her speak, she asked to do a “land acknowledgment.” I didn’t know what that was, but she was granted permission and said something about the land to scattered applause before we moved on.

As far as activist tactics go, it was pretty good.

It was much easier for a progressive moderator at a conference with mostly progressive attendees to just say yes than to try to have the woman forcibly removed. It’s a small-bore example of the strategic logic of nonviolent protest, and it succeeded in getting large swathes of progressive America to preemptively start doing land acknowledgments.

The 2024 Democratic platform, for example, commences with a fairly innocuous land acknowledgment, stating that they were gathering on “lands that have been stewarded through many centuries by the ancestors and descendants of Tribal Nations who have been here since time immemorial.” But the Native Governance Center’s guide to Indigenous land acknowledgments tells us, “Don’t sugarcoat the past. Use terms like genocide, ethnic cleansing, stolen land, and forced removal to reflect actions taken by colonizers.”

I think it’s worthwhile to consider the distinction here.

The Democratic platform land acknowledgment is a symptom of a party that is more focused on internal coalition management than on winning elections. What it says in your platform almost certainly doesn’t matter, but a disciplined political party focused on winning would not be making this sort of concession to activist demands. That being said, if hailing the stewardship of those who came before us became a widely adopted ritual in American life, that seems unobjectionable on the merits to me. It’s a bit cringe, but so is singing the national anthem at the start of a youth sports event. There’s never going to be a cringeless set of national rituals, and rituals are important.

But the stolen land claim is an ideological provocation that I think needs to be rejected. National Students for Justice in Palestine describes its mission as “supporting over 400 Palestine solidarity organizations across occupied Turtle Island (so-called North America).” I think both friends and foes of the anti-Zionist movement understand that they are sincere in their desire to delegitimize the Israeli state, and it’s worth taking seriously the fact that there is a parallel (albeit more far-fetched) movement to delegitimize the United States of America and that this needs to be contested by American liberals in a real way rather than appeased. Not least because it’s hard to explain what’s wrong with the increasingly deranged tenor of the Trump administration’s anti-immigration rhetoric unless you’re able to articulate the values of traditional American civic nationalism.

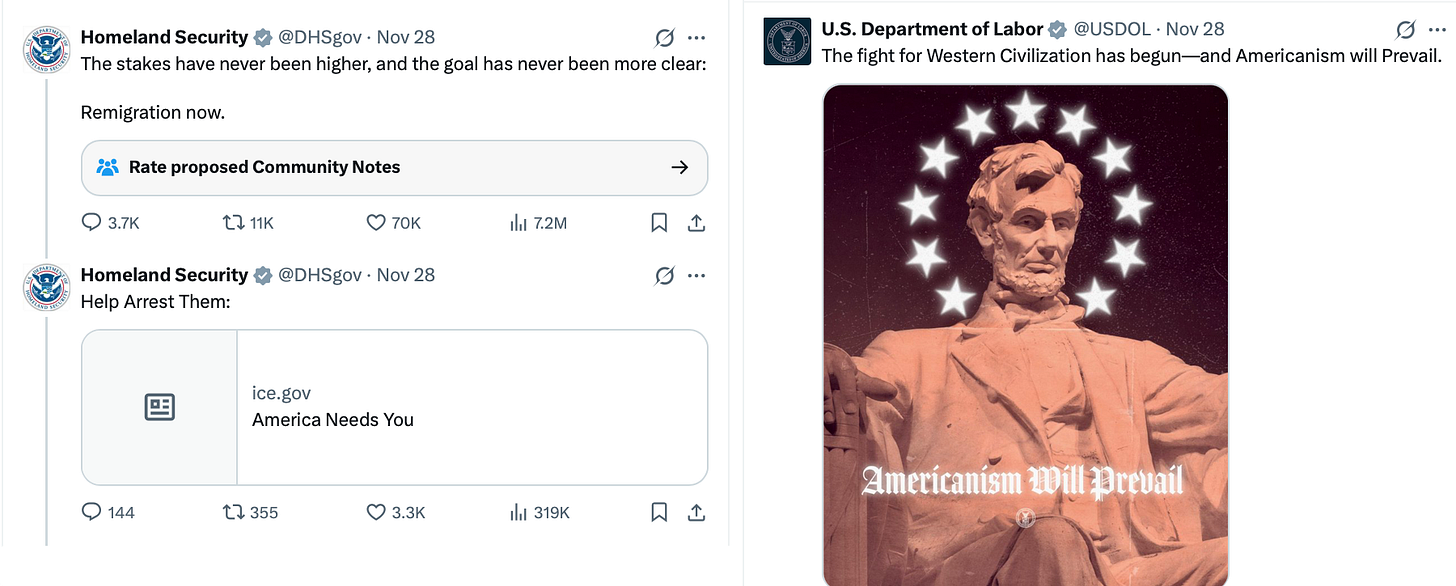

Abraham Lincoln, of course, understood Americanism far better than whatever groyper creeps are running the Labor Department. He wrote to Joshua Speed about the anti-immigration agitators of his time:

As a nation, we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “all men are created equal, except negroes.” When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics.” When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty — to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.

Lincoln isn’t the last word on the details of immigration policy, which is complicated and admits of a lot of nuance. But he should be the first word. America is a country whose institutions are committed to the noble principles of human freedom and equality, and we need to be able to say in both directions that those institutions are legitimate.