Donald Trump becomes president today.

And even though he campaigned for a year and a half and then served four years in office and then campaigned essentially nonstop through four years of Joe Biden’s presidency, I have remarkably little clarity on what he actually intends to do as president.

Which is not to say that we’re completely in the dark. He’s not going to champion higher taxes on the rich. Whatever he and RFK Jr. do under the slogan “Make America Healthy Again,” it’s not going to involve substantial new agribusiness sector regulation of the sort that farm-state Republicans oppose. The one thing we really know about Trump is that there’s usually less to his bizarre policy pronouncements than meets the eye. When in doubt, he tends to default to not actually doing anything or else just enabling conventional right-wing politics.

But there really is an incredible amount that we don’t know.

Not in the sense that I’m stomping my feet, complaining that the media isn’t telling us what’s really going on. I think the best reporters in the business simply don’t know what’s going on, and to an extent are left to write around their ignorance. Part of the problem is that Trump is secretive, hypocritical, and pathologically dishonest. But it’s also the large asymmetry between the partisan coalitions. If Kamala Harris had won the election, there would have been intense interest from Democratic Party-aligned media in the details of her transition. Not just in who was getting picked for what job, but what it signified. And this interest from left-of-center columnists and publications would be complemented by interest from Democratic Party elected officials and interest groups.

Republicans aren’t really like that. Liberals read more, and conservatives watch more television. Republicans are more interested in conservative ideology, and Democrats are more interested in specific issue areas. This means that while the right of course has its own factionalisms, there’s not much of a market on the right for granular policy-focused debates and inquiries. And in the absence of Republican pressure on Trump to clarify what he means, we’ve just been talking a lot about Greenland.

The obvious tariff question

On Inauguration Day, we’ve still got basically no idea whether Trump is actually going to implement his absurd campaign pledge to levy a 10 percent tax on all imported goods.

On the one hand, the fact that his team has not solidly committed to this suggests no. Most of the people in his orbit, including Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, sold the business community on the notion that Trump could be trusted by portraying the threat of tariffs as a negotiating ploy to secure concessions from foreign countries.

On the other hand, Stephen Miran, Trump’s incoming chief economist, wrote a discussion paper during the campaign making the case that most economists are mis-stating tariff incidence. His argument is that tariffs will not raise prices for American consumers, because exchange rates will adjust — the dollar will become more expensive, real consumer prices will be flat, and the Treasury will secure revenue. The tariff, in this theory, is essentially free money for the government that can offset the cost of other things Trump wants to do. Of course, he concedes that violent exchange rate swings could be financially disruptive, so maybe you want to implement them gradually.

A leak last week indicated that a range of Trump advisors are studying their ability to apply gradual tariffs via emergency powers, which suggests they really might do this.

The actual problem implicit in Miran’s analysis is that if the dollar responds to tariffs by appreciating enough that there is no increase in consumer prices, then you’re kneecapping American exporters and failing to provide any protection against foreign imports. When Miran first wrote his piece, I thought he was basically just doing a little campaign season lib-owning by pointing out that tariff incidence is more complicated than Kamala Harris made it out to be. His observation about exchange rates doesn’t actually support the policy. If he’s right, then tariffs are strictly bad for American manufacturing:

A US factory is disadvantaged in trying to sell products abroad due to the stronger dollar.

A US factory receives no benefit in trying to sell products at home, because the price of imports doesn’t rise.

The winner would be Americans who do extensive foreign travel. The higher price of the dollar would make it cheaper to rent a hotel room in Paris, and you wouldn’t need to pay a tariff. But is Trump actually going to do this? His team seems to think it’s a bad idea, to recognize that it won’t deliver their boss’s goals. Perhaps gradualism is an effort to talk him out of it? Jeff Stein recently published an article about how some advisors were pushing limited tariffs on a list of strategic goods. I might support that, depending on the list. But Trump immediately issued an angry denial. He says he wants to replace the IRS with an External Revenue Service to collect tariffs.

But, of course, we already have Customs and Border Protection to collect tariffs.

Financial markets are acting like they don’t really expect this to happen. Conservative media isn’t trying to figure out what’s going on. And I sincerely have no idea, in part because “Trump is genuinely crazy” and “Trump is trying to seem genuinely crazy as a negotiating strategy” are obviously going to look similar. It’s challenging to know how to cover someone whose allies say he’s a huge liar and you’re deranged lib if you take him seriously.

What does “mass deportation” mean?

The phrase “mass deportation” proved on the campaign trail to poll pretty well and also to upset liberals. So Trump kept promising “mass deportation,” and liberals kept raising alarms about Trump’s plan for “mass deportation.”

That’s a really good campaign tactic. Basically anyone can try to come up with popular slogans. The problem is that other people are likely to tune your slogans out or assume you’re lying. But if you can get your opponent to keep attributing your popular slogan to you, then you’re in great shape. It would be as if every right-winger on social media was complaining constantly that “Kamala Harris will protect reproductive freedoms.”

But what is Trump actually going to do on immigration?

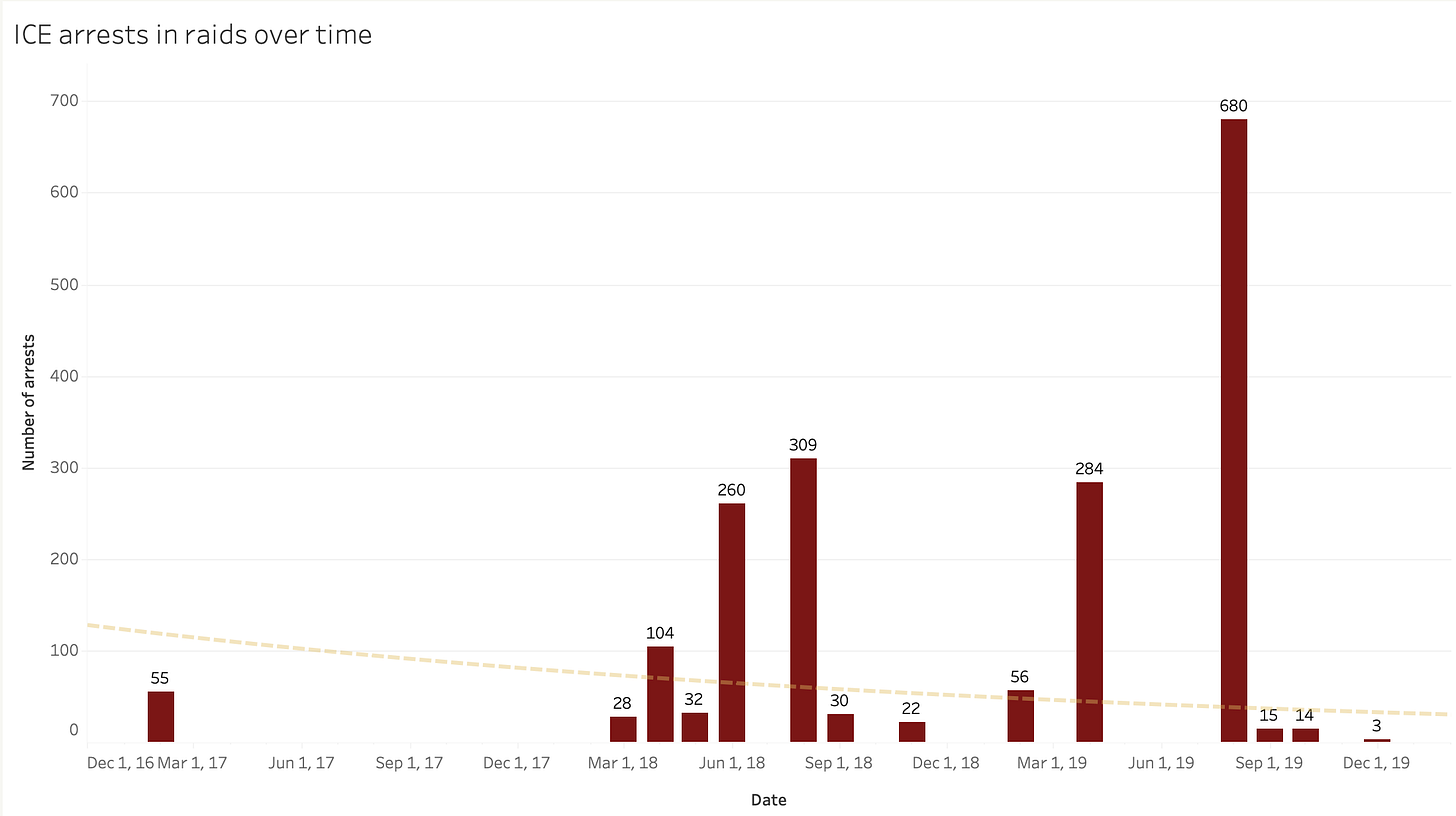

His incoming immigration czar, Thomas Homan, seems to have recently mentioned to House Republicans that there are actually severe resource constraints on ICE’s ability to deport people, so unless they get him a bunch more money, he probably won’t be able to meaningfully step up the pace of deportations. There was a report that his transition team wants to stage some high-profile workplace raids near Washington, DC right after the inauguration to send a message, but Homan said that’s not true. Then came word that there will be some kind of show of force in Chicago. Biden didn’t really do workplace raids at all, but even under Trump, they were incredibly sporadic.

Will Trump try to do workplace enforcement in a serious, consistent way? You can’t really deport America’s whole population of undocumented immigrants one by one. But it is possible that consistent workplace enforcement might induce employers to stop employing workers illegally, at which point the bulk of the population might “self-deport,” as Mitt Romney wanted them to. No president has ever really tried to do this, because to make it work at scale would, by definition, involve large economic disruptions.

But Trump has absolutely said he wants large-scale deportations and spent the campaign musing about large-scale detention camps. Is any of this happening? I have no idea.

Big campaign promises

After an election campaign in which Trump promised to end taxes on tips, end taxes on Social Security benefits, and give everyone free IVF treatment we’ve heard very little about these issues.

Instead, since he won, Republicans have pivoted to working on budget reconciliation instructions that will make all of TCJA permanent and offset the cost by repealing most or all of the IRA climate funding, and also cutting student loans and various programs for the poor. No big surprise there to anyone who was paying attention, even if it wasn’t highlighted by the campaign.

But what actually happened to no taxes on tips and no taxes on Social Security?

Those really were signature campaign themes for Trump. We know congressional Republicans don’t love those ideas, because they don’t really make sense and also don’t align with conservative tax policy priorities. But Trump is kind of a marketing genius and figured out that the contemporary Democratic Party doesn’t have a good answer to populist fiscal gimmicks. But is he going to actually follow through? It would be kind of bizarre to win an election after campaigning so heavily on this and then not try. But then again, it’s really unusual to win office and be a Day One lame duck. He can make zero effort to fulfill his campaign pledges, and what’s anyone going to do about it?

But I also wouldn’t count it out.

He’s a Day One lame duck, so other Republicans might try to claim the Trump mantle by championing these ideas; just because nobody is talking about it right now doesn’t mean it won’t be on the agenda. But it makes trillions of dollars of difference in a tax agenda that’s already hazy because we don’t know if pivotal Republicans will insist on minimizing spending cuts or on minimizing deficit reduction in the face of what’s sure to be a giant tax cut.

Free IVF is obviously bullshit. But this was part of Trump’s effort to moderate on abortion, which I think was central to his success. It’s gotten sort of airbrushed out of most election retrospectives, but reproductive freedom was one of Democrats’ best issues until Trump very firmly committed to breaking with the GOP base on this in a way that drove its salience way down. And yet, obviously, Trump got the votes and institutional support of lots of people who sincerely believe that abortion is murder, and presumably want to come up with some way to reduce the number of abortions that happen. The government is large and complicated, and there’s plenty that Trump might or might not do to advance the pro-life cause. But as my drafting this article, the conservative press is 100 percent invested in lib-owning and zero percent interested in exploring these questions.

It seems inconceivable to me, as someone who’s worked around politics for a while, that Trump could take no steps toward banning abortion and also face no blowback from the right. But he’s held it together so far. Will this deal stick? Will anyone try to challenge him?

The world abroad

Israel and Hamas reached a ceasefire agreement this week that was substantially similar to the terms the Biden administration has been pushing for months. What made the difference is that this time, Trump’s team joined in putting pressure on Israel to sign on the dotted line.

The basic politics of this are easy to understand. As long as the election campaign was underway, promising to be more pro-Israel than Biden discouraged Israel from agreeing to a deal, which in turn helped Trump pick up both highly motivated pro-Israel voters and highly motivated anti-Israel voters. With the campaign done, Trump could switch his position to Biden’s position and start his term with a peaceful situation in the Middle East. Very nice.

But what is Trump’s actual policy here? Or, frankly, anywhere?

He was the original “ban TikTok” guy, but then after a TikTok ban passed Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support, he flip-flopped and decided it’s great for America to be programmed by the Chinese Communist Party. More broadly, he owns the tough on China brand, but he’s appointed the straightforwardly pro-CCP, anti-Taiwan Elon Musk as his shadow president. He criticized aid to Ukraine, which was consistent with what he said when he was president. Except when he was president, the US actually delivered more aid to Ukraine, not less. Now some parts of his team are talking about getting tougher on sanctioning Russia — Sebastian Gorka says they’re going to give Ukraine more weapons than ever. His Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, is an old-school GOP national security hawk. But on the other hand, he is very insistent on installing the under-qualified Pete Hegseth at the Department of Defense, and he’s standing behind Tulsi Gabbard as Director of National Intelligence.

I have no idea what’s actually going on here. In my darker moments, I think America has already lost the New Cold War, because Trump and Musk are on the other side.

I worry that over the next four years, we’ll abandon Biden’s nascent efforts to rebuild manufacturing, abandon Ukraine, abandon Taiwan, and implement a tariff policy that hammers American exporters, all while the president spends his time gleefully shitposting about Canada and picking fights with Latin American countries over deportations.

Other times, I think super-hawk nationalist warmongers are in the driver’s seat.

Or maybe it’s both. Or neither. One of the big frustrations of journalism is you write the stories about what you do think you know, not what you know you don’t know. And yet, I find that almost across the board, Trump, despite being incredibly famous forever and ever, is irreducibly enigmatic. Being a liar is core to his brand. It’s something that his supporters like about him, so you can’t take anything he says literally or ever predict what he’s going to do — which, in his books, he says is a reason it’s good to be a liar.

I’m already confused and exhausted on his very first day in office.