Don’t worry, I’m eventually going to write quite a lot about the consequences of Donald Trump’s election victory. For now I want to keep focusing on the lessons that I think Democrats — and everyone — can learn from the result. Three that immediately stand out to me are:

Identity politics — viewing racial groups as homogeneous “communities” to be targeted with appeals to collective grievances — is not an effective way of winning over Hispanic (or, probably, Asian) voters.

People care about inflation more than about unemployment.

The educated professional class has become dangerously out of touch with the rest of the country.

(I’m thinking about adding a fourth about urban politics; we’ll see.)

In yesterday’s post, I talked about the failure of identity politics. In tomorrow’s, I’ll talk about the divergences between the educated professional class and the rest of the country. Today I’m going to talk about inflation.

In 2021, there was a fierce debate, both within the Biden administration and among the general left-of-center commentariat, about how much to worry about inflation. For example, in May 2021, Larry Summers wrote:

Even six months ago, it was reasonable to regard slow growth, high unemployment and deflationary pressures as the predominant risk to the economy. Today, while continuing relief efforts are essential, the focus of our macroeconomic policy needs to change…Inflationary pressures are mounting…How much does it matter whether inflation accelerates? In general, increases in inflation disproportionately hurt the poor and are associated with reductions in trust in government. Progressives might consider the role that inflation played in electing Richard M. Nixon in 1968 and Ronald Reagan in 1980.

In February 2021, Olivier Blanchard, another prominent macroeconomist, wrote a detailed argument that the Biden administration was spending too much on Covid relief with the American Rescue Plan, and that this would generate a surge of inflation. The argument included a simple model whose predictions ended up being close to what actually happened.

Other economists pushed back hard against Blanchard and Summers, arguing that inflation was due to transitory factors, and that it was important to keep spending in order to preserve full employment. One of these was Paul Krugman, who declared himself “a card-carrying member of Team Transitory” — “Team Transitory” being those who thought inflation was mostly due to pandemic disruptions and would fade on its own. There was even a live debate between Krugman and Summers in early 2022. But by late 2022, Krugman issued a mea culpa, and admitted that Biden’s American Rescue Plan had exacerbated inflation:

In early 2021 there was an intense debate among economists about the likely consequences of the American Rescue Plan, the $1.9 trillion package enacted by a new Democratic president and a (barely) Democratic Congress. Some warned that the package would be dangerously inflationary; others were fairly relaxed. I was Team Relaxed. As it turned out, of course, that was a very bad call.

Economic analyses of the inflation surge of 2021-22 generally assign the American Rescue Plan some share of the blame.

Ignoring Summers’ warnings, and believing Team Transitory, might have cost the Democrats the 2024 election. I’m no political scientist, but there are reasons to believe that the burst of high inflation in 2021-22 was one factor in Kamala Harris’ loss.

Why inflation probably mattered in this election

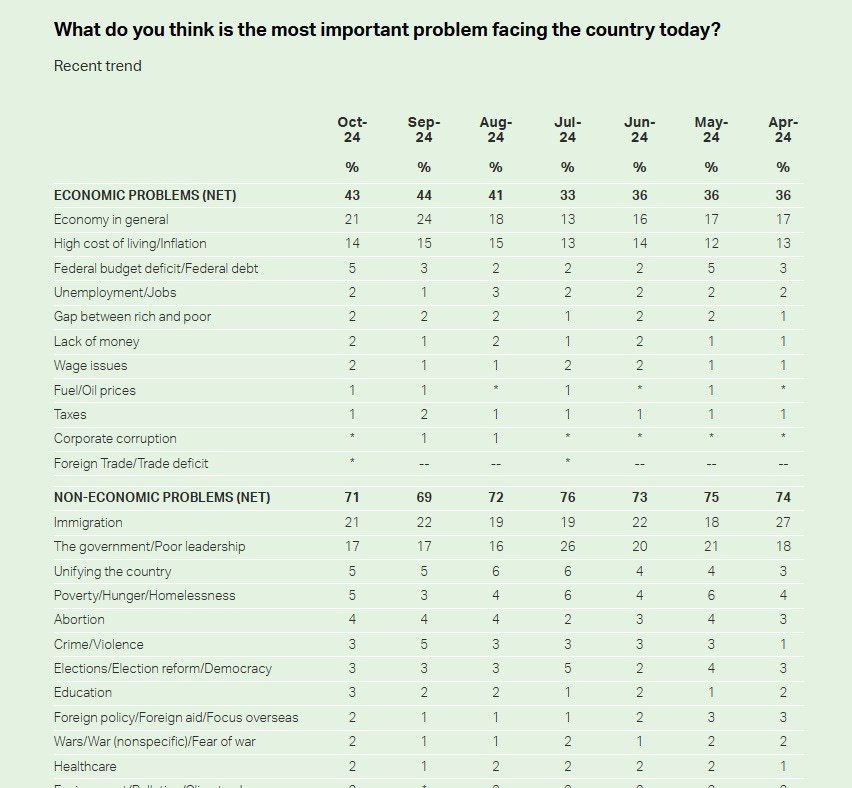

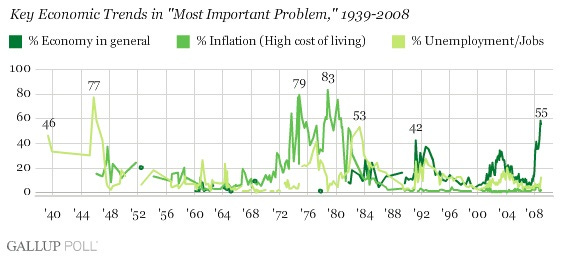

The first reason we should think inflation mattered is that people pretty consistently said it mattered. On Gallup’s long-running “most important problem” survey, inflation consistently ranked as the most important specific economic problem that people mentioned, right behind “economy in general”.

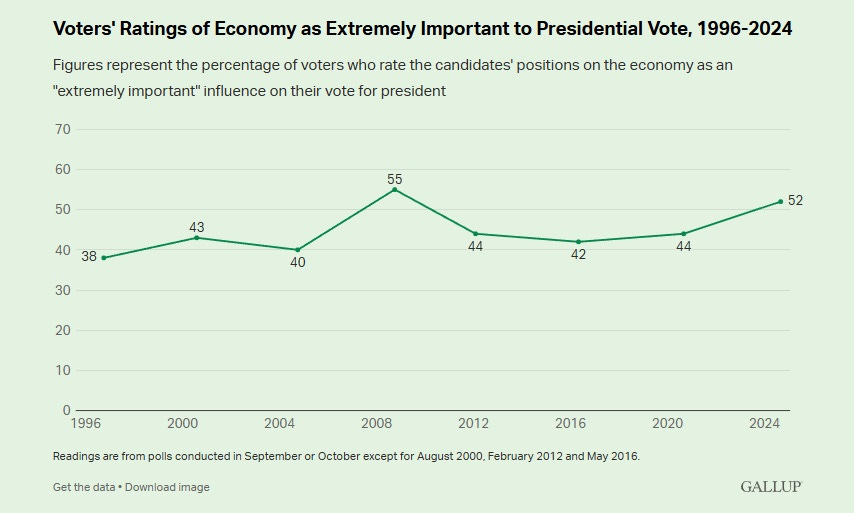

A lot of other surveys showed similar results. And the percentage of people who told Gallup that the economy was “extremely important” to their presidential vote was unusually high — almost as high as in 2008, when the financial crisis had just devastated the U.S. economy:

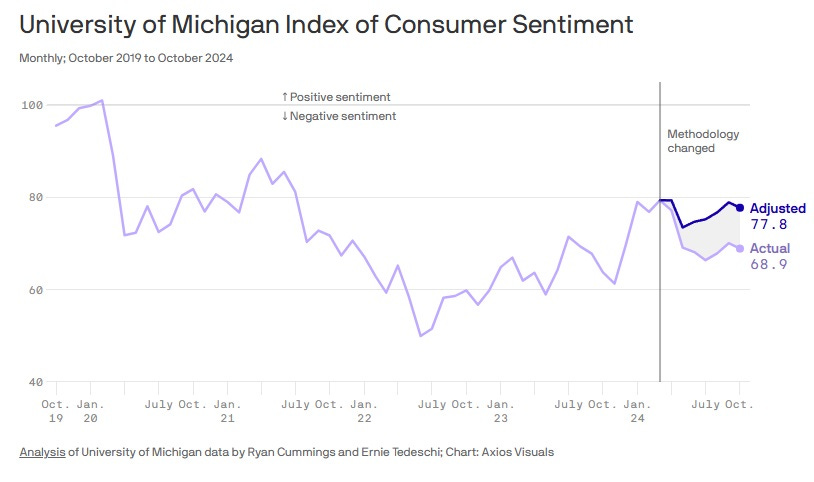

And of course consumer sentiment was pretty low, even after adjusting for changes in methodology:

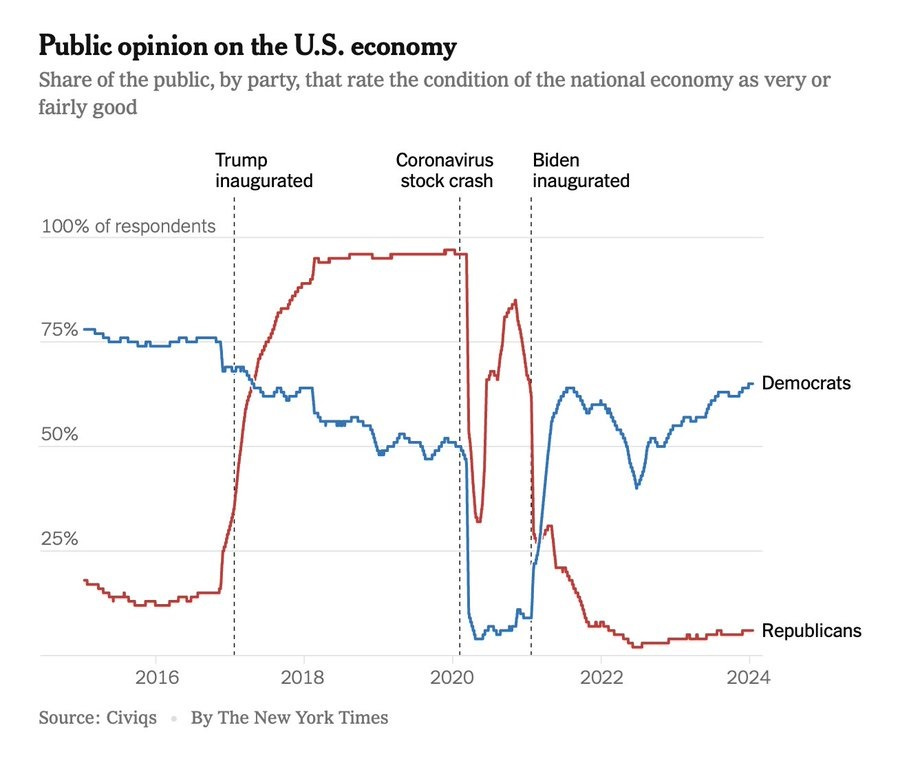

Now, it’s possible that this was mostly just Republicans complaining about inflation because it felt more substantive than talking only about more social/cultural grievances like wokeness, immigration, trans stuff, etc. After all, opinion on the economy shows a very partisan pattern depending on who’s in the White House:

It’s a pretty good bet that Republicans will suddenly “discover” that inflation in America is actually low now, and give Trump the credit.

But if you look historically and across countries, it really looks like inflation tends to make voters particularly mad. Research often finds that cumulative inflation over a President’s term in office — not just the current inflation rate — affects presidential approval and election performance. If you look at Gallup’s long-running survey, you’ll see that the inflation of the 1970s dominated Americans’ complaints even more than the unemployment of the Volcker recessions in the early 80s, or the recession of the early 90s:

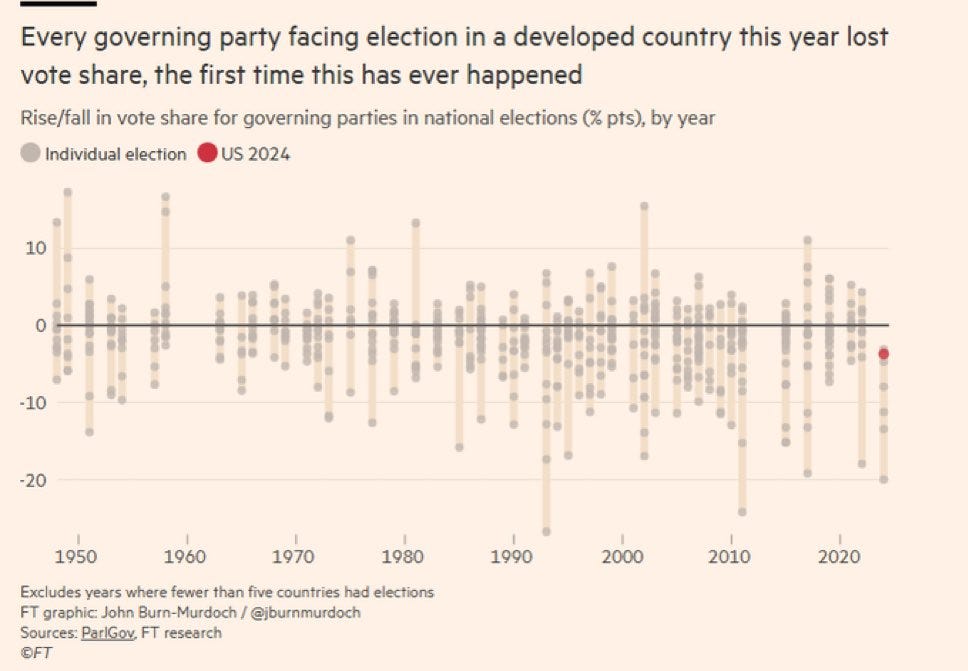

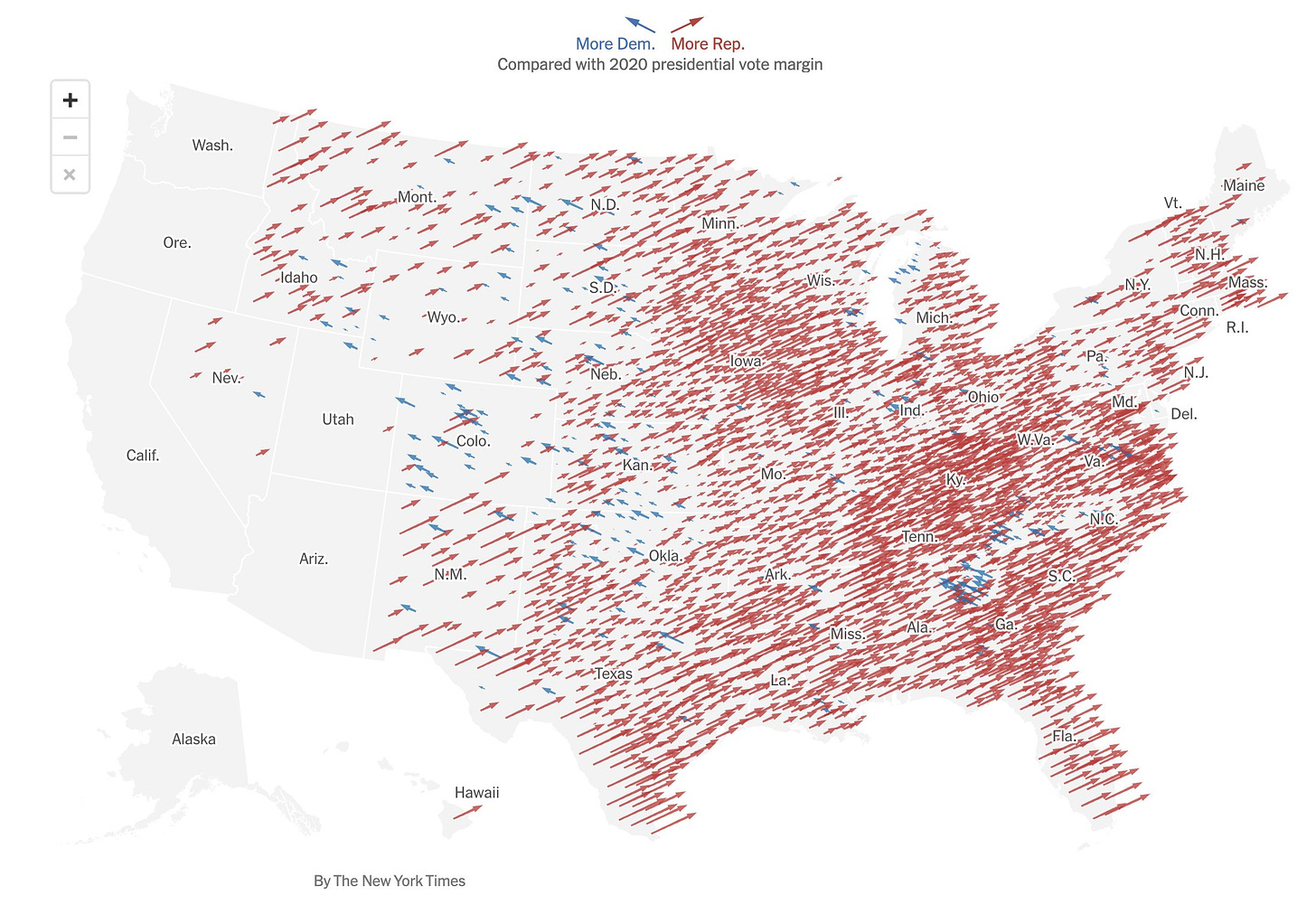

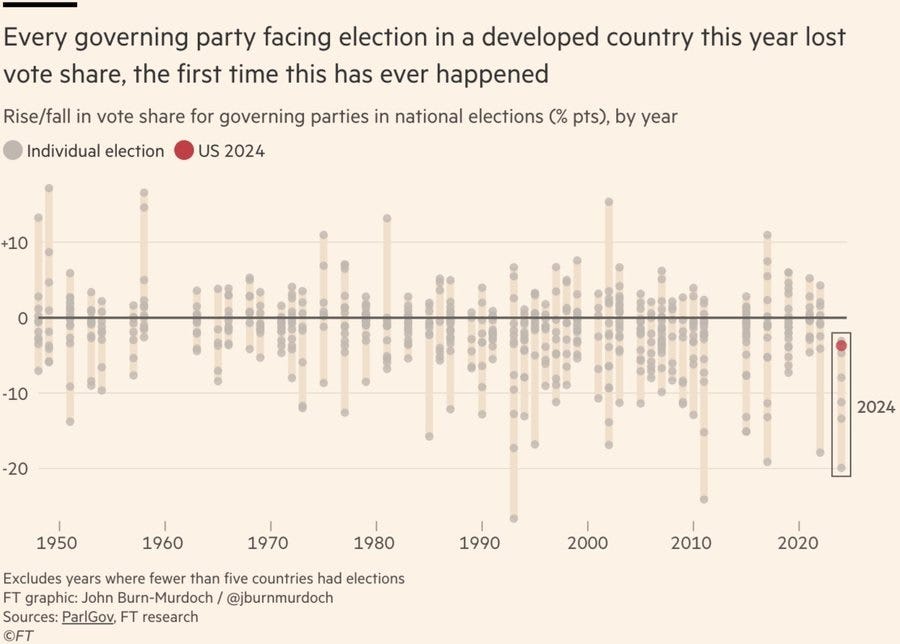

And if you look at other countries, you’ll see that governing parties in every other rich country have seen their vote shares go down this year:

There are relatively few factors that are affecting all rich countries at the same time. A backlash over immigration is another possible common factor, but the list is basically just that plus inflation.

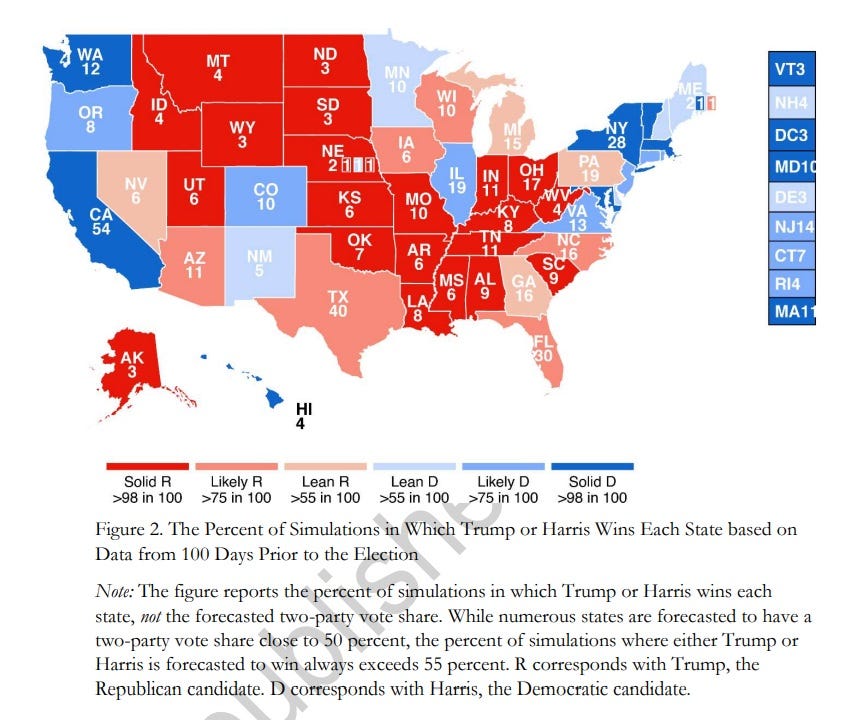

On top of that, there was a model that predicted the election outcome quite well. An interdisciplinary team of researchers created a model based on presidential approval ratings and economic conditions in each state, and they ended up predicting each state correctly:

It might be a fluke, but the same model got only one state wrong in 2020 (Georgia), so that’s pretty encouraging. In any case, the model relies partly on economic fundamentals — measures of the labor market and real wages. And real wages depend on inflation. So since labor markets are generally very strong all across America, the erosion of state-level wages by inflation is going to be the main economic factor that led this model to forecast a Trump victory.1

So I think it’s safe to say that while it’s possible inflation mattered less for Trump’s victory than people say on polls, it did matter at least somewhat.

Why inflation makes voters even angrier than unemployment

Let’s talk a little about macroeconomics for a second. Most mainstream macroeconomic models assume that there’s some sort of short-term tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. If the Fed lowers interest rates or does quantitative easing or otherwise prints money, the general consensus is that unemployment will go down and inflation will go up. Similarly, if the government borrows and spends money and the Fed doesn’t counteract this by raising interest rates, the general consensus is that you’ll get faster growth, more jobs, and rising prices.2

Macroeconomic policy then becomes a question of how to strike the right balance. We want everyone to have a job. We don’t want inflation to go about 2%. But if we have to choose between these two things, how do we choose? In economic models, the relative degree that policymakers should care about inflation versus unemployment is determined by a social welfare function — basically, how much each of these economic ills makes regular people unhappy. A lot of economic research is dedicated to figuring out what that welfare function, and there’s not really a consensus.

But the experiences of the 1970s and the 2020s are teaching us that in America at least, people seem to get even madder about inflation than they do about unemployment. And the question is why. I actually wrote a post about this back in March of 2021, shortly after the American Rescue Plan was passed:

The basic story here comes from a survey Robert Shiller did in 1990. Basically, inflation tends to make people’s purchasing power go down, because their wages can’t keep up.3 This makes people poorer, and people do not like to be poorer.

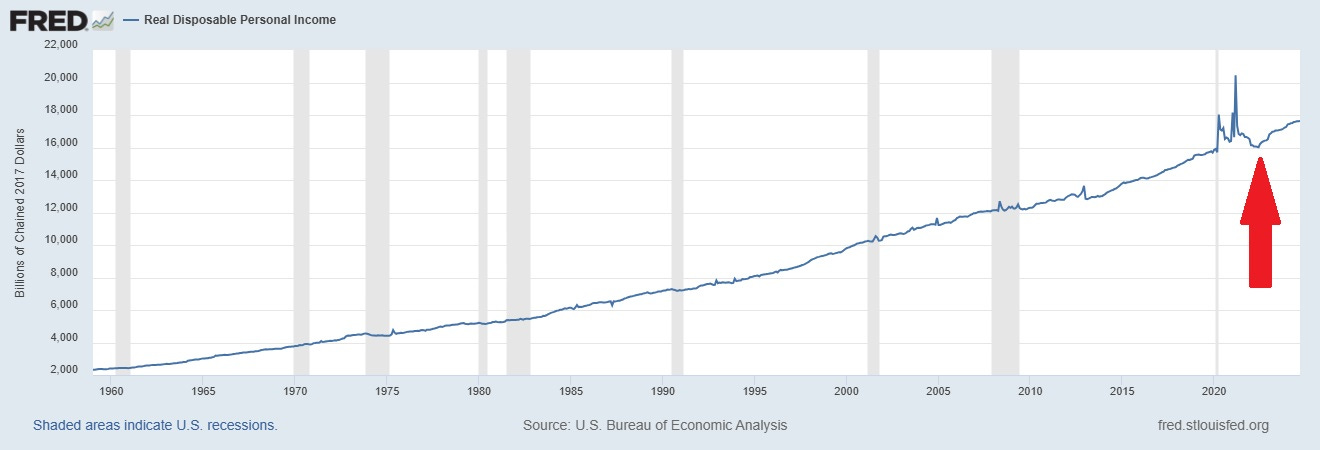

The inflation of 2021-22 definitely made people poorer. In fact, the drop in real personal disposable income from mid-2021 to mid-2022 was more severe than the Great Recession or the 1970s inflation!4

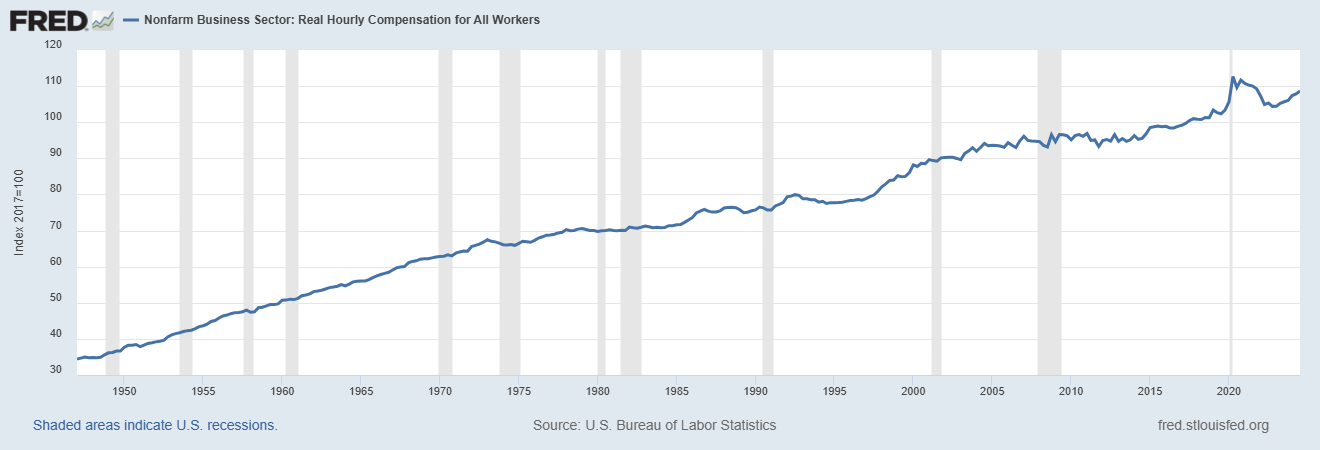

This was caused by a combination of the end of pandemic relief, and falling real wages and other income due to inflation. In 2021 and 2022, Americans’ real wages suffered their biggest drop in postwar history, thanks to inflation5:

Remember, real wages are a key economic input that went into the model that managed to successfully predict every state’s election result. People really don’t like it when their real wages go down!

One key thing to understand is that this sudden impoverishment happened to most Americans. Rising consumer prices affect everyone, from the rich to the poor, the employed and the unemployed, the old and the young.

In a recession, on the other hand, the negative effects are largely concentrated. If you’re one of the unlucky people who loses their job, you take a huge hit. But if you’re not one of those people, you probably do OK. Maybe your wages grow more slowly for a few years, and maybe you have to stress out about the increased possibility of being laid off. But in general, the harms of inflation are diffuse while the harms of unemployment are concentrated.

If you’re a moral philosopher, an activist, or an economist estimating a social welfare function, you may prefer harming a lot of people a little bit with inflation to harming a few people a lot with unemployment. But a democracy doesn’t vote based on social welfare. It’s one person, one vote. So if unemployment harms 10 million people a lot, and inflation harms 200 million people by a moderate amount, it’s clear that inflation will directly harm a much larger number of voters.

The social welfare function and the “get your butt kicked in an election” function are two very different things.

I actually suspect that there are other reasons why inflation bothers voters even more than unemployment. Inflation is something that’s obviously beyond an individual’s control — if the price of eggs goes up, you can choose not to buy eggs, but otherwise there’s not much you can do. But unemployment is something that individuals do exercise some degree of control over — if you work a bunch of extra hours during a recession and establish a good relationship with your boss, maybe you can avoid getting laid off.

In general, I think people are less worried about risks they have some control over, even if the overall level of danger is higher. Look at how people are more afraid to fly than to take long road trips, despite road trips being much deadlier per mile. The leading theory is that in a car you have some control over your safety, while in a plane you have basically zero control. Similarly, I suspect that inflation makes people feel powerless, like being stuck in a crashing airplane.

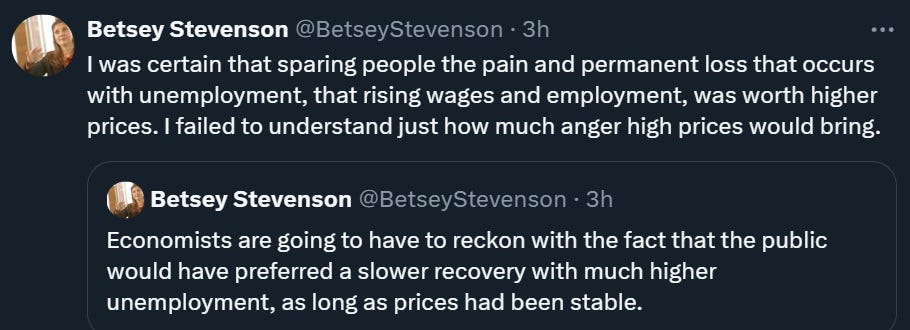

In any case, this is probably an important area for survey research to explore. But in the meantime, Democrats need to remember that full employment doesn’t necessarily mean an economy that Americans are happy with. If it comes at the expense of rapid inflation, that price is going to be one that most Americans aren’t comfortable paying.

Democrats should be wary of macro-progressivism going forward

I’d like to say a little more about the debate over the American Rescue Plan in 2021. While Paul Krugman and Larry Summers viewed their argument in purely technical terms, some economists and commentators did come at the debate from an ideological angle. In general, spending more was considered the progressive position, while spending less in order to avoid high inflation was considered more centrist or moderate.

This makes sense — full employment disproportionately benefits the least well-off in society. The lowest-paid workers are often the first to be fired in a recession and the last to be hired in an expansion, so the longer you can keep an expansion going, the more poor people can have jobs. Also, full employment tends to push up wages, especially at the lower end of the scale — in fact, even as most Americans lost purchasing power during the inflation of 2021-22, the bottom 10% of American workers actually saw their real wages rise.

This July, I wrote about how some influential progressive think tanks basically push for full employment all the time, and downplay worries about inflation:

Some progressive economics commentators — I will not name names, because I’m trying to be a less confrontational blogger these days — also consistently downplayed the risks of inflation and extolled the many benefits of full employment during Biden’s tenure in office.6

In retrospect, whether or not this was a good move from a moral standpoint, it looks like a big mistake from an electoral standpoint.

I hope that these commentators are reevaluating their beliefs. And I hope that Democratic politicians, staffers, and donors are reevaluating the paradigm as well. Full employment is great, all things equal. But sometimes the price of full employment is too high — not just for the majority of Americans who have to endure years of erosion in their purchasing power, but for everyone who has to suffer from the election of leaders like Donald Trump.

Update: Good to see some left-leaning economists quickly coming to the same conclusions.

Our task now is to get the ear of Democratic politicians, which will probably require wresting it away from some progressive think tanks and Twitter posters.

The other factors that influence elections — culture wars, charisma, narratives, and so on — are all represented by the presidential approval ratings that get fed into the model.

This effect will generally be magnified if nominal interest rates are at the zero lower bound, as they were in 2021.

This sounds like one of those bleedingly obvious things that economists need a research paper to prove to themselves, but which every normal person with half a brain already knows. In fact, it’s not. Inflation drives up wages as well as prices — there’s no obvious reason why wages should go up more slowly than prices during a period of high inflation. But in fact, that is what happens, and economists don’t know why.

Actually, not all income measures show the same thing. Real median personal income did much worse in the Great Recession than in the post-pandemic inflation. Real median household income fell significantly in both episodes.

Some of this was due to a composition effect — low-wage workers returning to work dragged down the average. But wage measures that control for composition effects also found that wages failed to keep up with inflation in 2021-22.

The most extreme form of this “macro-progressivism”, of course, is the cult-like movement known as MMT. Most macro-progressives want nothing to do with MMT, of course. But sometimes their beliefs can seem like MMT’s more reasonable, wonkish cousin — always pushing for a little more fiscal stimulus, rain or shine.